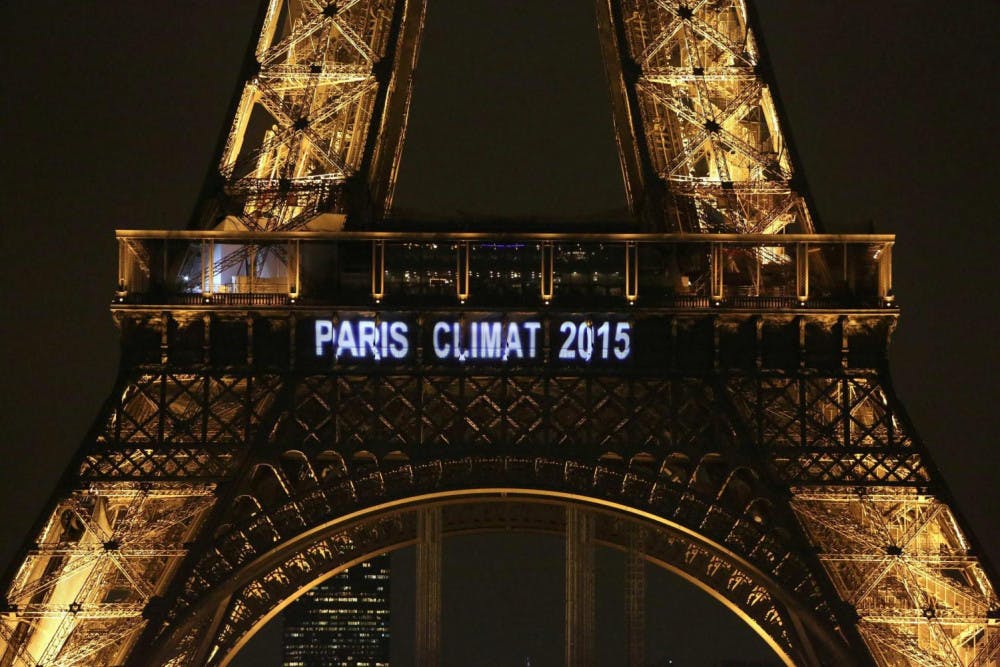

Were the Paris climate talks of 2015 a success or a failure, and where do we go from there? These were the central questions in a talk entitled “Adequacy and Equity under Neoliberal Climate Governance: Assessing the Paris Moment” on Thursday, Feb 25. Co-sponsored by the Geography Department and the Rohatyn Center for Global Affairs as part of the Howard E. Woodin ES Colloquium Series, the presentation featured Timmons Roberts, Ittleson Professor of Environmental Studies and Professor of Sociology at Brown University.

Standing before a packed room of ES majors, faculty members and curious students looking to expand their knowledge on a deeply relevant issue, Roberts opened his speech with a few stark statistics. Due to the nature of global climate governance, people in the least developed countries – including Myanmar, Nepal and Bangladesh – are five times more likely than anyone else to die from natural disasters. Comprising only 11 percent of the total population, the most disadvantaged civilians of the world live in areas that experience 21 percent of climate-related disasters and witness 51 percent of climate-related deaths.

These disproportionate numbers stem from what researchers have dubbed “the climate paradox,” in which the least responsible parties – those that have contributed least to carbon dioxide emissions – are the most vulnerable to climate change. Lacking the proper infrastructure to respond to environmental damage caused by global warming, these lesser developed countries pay dearly for the climate policies instated by and for their wealthier, more powerful neighbors.

So did the United Nations Climate Change Conference of 2015 – also known as the 21st Conference of the Parties, COP 21 or the Paris climate talks – address this inequity? Roberts, who brings the students in his climate and development lab to the event each year, unpacked the details of last December’s Paris agreement, a plan to reduce climate change as negotiated by the 195 participating countries, and its long-term implications for the world. Because countries had not settled on many concrete measures before the 2015 conference, nearly every single issue – from peaking emissions to net reductions – was on the table.

A major goal outlined in the 12-page document is to “hold the increase in global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, recognizing that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change.” Roberts cast a wary eye on this clause, however, explaining that researchers do not know if the 1.5°C limit is even enough to maintain a safe long-term environment. Besides, with human activity already elevating the global temperature by 1°C, the 1.5°C threshold may turn out to be more difficult to uphold than researchers imagine.

Roberts provided a historical context for the Paris talks by explaining the evolution of global policies across the past few decades. In 1972, representatives convened in Stockholm to piece together a pre-cautionary approach to climate change. At the Rio Earth Summit in 1992, the cost of conservation entered the international dialogue. Five years later, the Kyoto Protocol institutionalized liberal environmentalism, and certain wealthy countries became subject to binding limits on emissions.

More recently, the Copenhagen conference in 2009 marked a significant turning point in global climate governance, as officials ushered in a new process of pledge and review entitled the “Intended Nationally Determined Contributions” (INDC). The United States and China, the two largest emitters, made initial announcements of their national pledges in 2013, creating a domino effect throughout the international community. In total, 189 national pledges were submitted, all of which reflected a general willingness to make meaningful and pragmatic changes to their climate policies. With these INDCs in effect, the global average temperature went down slightly, from 3.6°C to 2.7°C.

“It wasn’t enough, but it was something,” Roberts said, before quoting the following line from George Monbiot in The Guardian: “By comparison to what it could’ve been, it was a success. By comparison to what it should’ve been, it was a disaster.”

According to Roberts, the shift from top-down command to a completely flexible and voluntary approach gave birth to a system of “shared irresponsibility.” Plagued by a lack of accountability, the policy enacted in Copenhagen has been criticized as inequitable and undemocratic.

“The pledges are not binding,” Roberts stated. “Logically, wouldn’t a better way of solving this problem have been figuring out a budget and dividing it up by a fair burden-sharing formula? If I were king of the world, that’s what I would do. That’s the rational management approach. We tried that for 15 years, but countries simply didn’t sign up [at the Kyoto Protocol].”

The Paris talks strived to incorporate all present parties at the conference in a long-term plan for environmental conservation. However, the lack of binding commitments and enforcement measures make some experts doubt the efficacy of the agreement. Countries are expected to sign the document and implement it in their own legal systems between April 22, 2016 (Earth Day) and April 21, 2017, but there is no established consequenc if they fail to do so. Furthermore, each nation will determine their own goals of emission reduction. The Paris agreement operates on an unofficial “name and shame” system, also known as the mantra of “name and encourage.” The proposed measures will not go into effect until the 55 parties who produce over 55 percent of the world’s greenhouse gas have signed.

Roberts pointed out that the flexibility granted to participating countries is entirely strategic.

“Countries worried about their sovereignty don’t want to be told what to do, but they may go beyond what they are asked to do,” he explained.

For instance, knowing that the appearance of coercion might lead to a political blockade, President Obama purposefully used the word “should” instead of “shall” throughout the U.S. treaty. 66 senators must agree to the proposed measures, which may be difficult given the nature of the people occupying those seats.

Based on the new book Power in a Warming World, which Roberts co-authored alongside David Siplet, Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies at the University of Colorado-Boulder, and Mizan Khan, Professor of Environmental Science and Management at North South University in Bangladesh, the speech emphasized the importance of a neo-liberal climate governance that exemplifies both efficacy and equity. Deemed by Roberts as the “holy grail of climate justice,” this approach is partially lacking from the Paris agreement.

Because the voluntary aspect of the Paris agreement is a far cry from the hard-hitting conservation policies that the world so desperately needs, Roberts urged the audience to spring to action. Now is an opportunity for citizens to hold their governments accountable, particularly as the opportunities to enact radical change become fewer and farther between.

“The kinds of solutions to our climate problems that we can put forward now in 2016 are really limited. We used to be able to bring out state regulations or strong international agreements,” Roberts stated, referencing the binding 1987 protocol to address the hole in the ozone, as well as the extra decade once allotted to developing countries like China and India to reduce their carbon emissions.

In light of the recent presidential primaries, perhaps it was fitting that the first question posed after the presentation concerned Donald Trump. The controversial Republican candidate has expressed the intention to back out of the Paris agreement should he assume office.

“I feel like I have to ask – what effect would Trump have on U.S. agreements with other countries?” a student asked.

“It’s hard to imagine Trump being very multilateral,” Roberts responded, his understatement prompting laughter from the crowd. “This problem needs a global solution, and the U.S. acting unilaterally is not a good approach. A lot is on the line.”

The moral of the story? Elections matter – and the full implications of the Paris talks will continue to come to light as countries choose whether or not to opt into these national pledges.

Speech Contextualizes Paris Climate Talks

Comments