With the 2016 deadline of carbon neutrality looming closer, the College’s alternative energy profile is more diversified than ever. We’re powered by sun, wind, trees and now… cow manure? Fear not, the odorless gas produced from the quintessential Vermont scent won’t force you to hold your breath on campus. And, for the expected 40 percent reduction in carbon emissions, the College thought it was an alternative energy worth sniffing out.

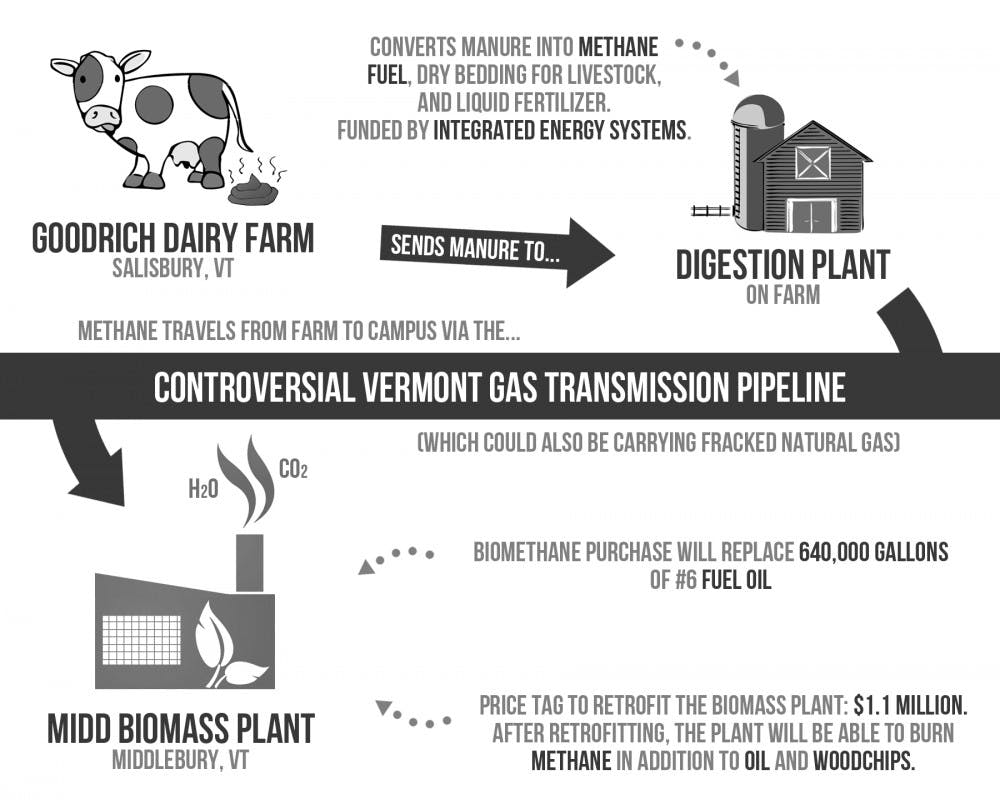

Bio-methane is an odorless and carbon-neutral fuel that will replace 640,000 gallons of number 6 fuel oil that the College currently burns to meet campus energy demands. Goodrich Farm, about 7 miles away from campus in Salisbury, VT, has contracted with a private developer of Integrated Energy Systems to build a digester on their farm that would produce bio-methane, a dry bedding material and a liquid fertilizer — all derived from mixture of mostly cow manure and corn.

Professor of environmental science Marc Lapin brought up the agricultural consequences of increased bio-methane demand.

“One thing bio-methane does is that it continues to support a non-sustainable agriculture production of massive milk production based on a lot of corn and industrial agriculture that produces greenhouse gases,” Lapin said. “If that system is going to persist, I think it’s better to make fuel out of it that continue to spread excess nutrients on the land and on the surface of the soil that are washing into the water. Producing bio-methane is a better solution than how most manure is handled now.”

In the early planning stages, the bio-methane project had both logistical and economic issues with on-campus storage and transportation. But with the convenient and timely approval of the construction of Phase I of the Vermont Gas pipeline — Addison Rutland Natural Gas Project — bio-methane became a feasible option for the College.

Environmental controversy surrounding the VT Gas pipeline persists as a result alleged fracked gas that the infrastructure will transport. Jake Nonweiler ’14.5, who did his senior research project on the pipeline last fall, mentioned reasons for widespread local concern about the pipeline.

“Environmental impacts of the pipeline will be significant, but I think it depends on your point of view,” Nonweiler said. “A lot of people think the pipeline isn’t a good idea because it’s still carrying fracked gas from Canada. So even if it’s not coming from Vermont, it’s still not appropriate to go through Vermont, which is a valid concern. But a lot of companies, like International Paper, one of their reasons for doing it is they’re going to see huge carbon reductions [using natural gas], instead of buying fuel oil.”

In addition to concerns over fracking, the total proposed pipeline route — Phases I, II, and III — from Canada to an International Paper mill in Ticonderoga, NY, will run through private property and residences in Vermont. According to the Vermont Gas website, the majority of business owners and residents besides those in Middlebury and Vergennes will not be able to tap into Phase I of the pipeline for local energy use until after 2016.

Despite these outside concerns, the College chose to support the construction of Phase I of the pipeline, keeping in mind how the infrastructure would benefit both the bio-methane project and the local economy due to the low price of natural gas compared to fuel oil.

“I feel that the College was not that big of a piece of it [the approval of Phase I],” Nonweiler said. “Vermont Gas had so many supporters and customers that are going to access that pipeline that the College was kind of like an addendum, an additional supporter but not the main supporter that made the pipeline happen.”

“Powerful economic interests wanted it [permit of Phase I] to go through,” Lapin said. “Even if the College had gone against it, it still would’ve gone through.”

In response to the possible hypocrisy the College faces by using the controversial pipeline, Byrne said “we’ll be burning some of the gas that came from elsewhere [fracked gas from Canada], but we’re not buying that gas. We’re buying the bio-methane that’s going into the pipeline.”

Nate Cleveland ’16.5, a member of the Carbon Neutrality committee on the Environmental Council said that environmental sustainability transcends the College.

“It’s great to be a proponent of global sustainability and global carbon neutrality, but you can’t expect a small liberal arts college to do that by itself,” he said. “I think the first step into doing that mission of global carbon neutrality is getting the campus carbon neutral.”

Lapid said that the carbon cycle is everywhere; it is hubris to think that carbon can be controlled. However, he noted some goals the bio-methane project could accomplish.

“What responsibility in global carbon neutrality can an institution like a College take?” he asked. “Education and demonstration. Is demonstrating that you can use manure for heating buildings a good thing, given the way our systems are? Yes.”

Byrne added that there is potential for further benefit by the pipeline to be available to farms who want to produce bio-methane.

“In the agreement with the public service board, the Vermont gas company is required to make the pipeline available for other bio-methane projects,” he said. “On balance, this is a good thing.”

Overall, Lapid said that it was a complex issue.

“Looking at it from an energy and pollution point of view, it makes sense,” he said. “Looking at it from the agricultural systems point of view, there’s something wrong… Is the College goal of carbon neutrality worth all these trade-offs?”

Bio-methane Purchase Stirs Criticism

Comments