Midway through a semester of routine cheating, an economics professor told Billy – whose name has been changed to protect his identity – and his friends to write down their names and where they sat in the examination room. The professor’s unvarnished command plunged Billy into an emotional apocalypse.

“We had been going overboard with the cheating. That whole week we were freaking out – what are we going to tell our parents? What are we going to do?”

Billy and three other friends had sat in a line together, the smarter of his friend passing solutions down the line. In a class of 25 students in Warner Science Building and no proctor, Billy would copy the answers from his friend to the left and down the line the answers went, with little effort to conceal their shifting eyes.

Even as he was in crisis, the thought of self-reporting never crossed his mind.

“We were absolutely sure it was 100 percent us,” he recalled. “There was no good reason to report it. If it was coming out we’ll hear about it within the next few days. I thought about telling my parents, just because I couldn’t keep it to myself, but I had my friends.”

But the twists just keep coming. They overheard later that week that it was, in fact, another group of guys in that same exam room that got caught cheating—not Billy and his friends. “My guess is that someone pointed them out. It shows the prevalence of cheating on campus. In a class of about 25 students, pretty much half the class cheated in that exam room.”

“It was a huge wake-up call,” Billy said, throwing his hands down in one of the few statements he made without stumbling through words like pretty much or I guess. “We were saying to each other that we will never cheat again and that we’ll just take the F.” But even after nearly getting derailed, he admits that the experience “didn’t completely reverse” his cheating habit.

What makes Billy’s story so compelling is that he is emblematic of a larger trend.

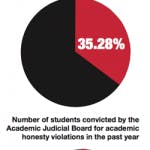

According to a survey last spring conducted by Craig Thompson ’14 for his Economics of Sin class, 35 percent of the 377 surveyed students admitted to violating the Honor Code at least once in the past academic year (2012-13), the latest volley of cheating allegations landing on Associate Dean for Judicial Affairs Karen Guttentag’s desk just last week. But 97 percent of the self-admitted Honor Code violators in his survey went uncaught.

“If I were to take those numbers at face value, I’d be very concerned about what it means for us and what it means for the student body,” said President of the College Ronald D. Liebowitz, who admitted to bringing cheating charges against students as a professor. “I’ve been here for 30 years and I’ve always been concerned about the veracity of honor codes like the one we have.”

Even though the percentage of self-reported cheaters last year was only slighter higher than those in 2008, the number of convictions for cheating – excluding plagiarism, which is less cut-and-dry – is climbing. According to the Honor Code Review Committee report published last spring, the number of instances in which a student was found guilty of cheating increased four-folds over the course of just three academic years.

But it’s tricky business figuring out why cheating convictions and cases of self-reported cheating are on the rise. Dean of Judicial Affairs Karen Guttentag said there are only theories right now and no definitive answers to the why questions.

“Maybe it’s a reflection of an increase in comfort in admitting to cheating,” she said. “But sadly, my sense is the taboo on cheating seems to be weaker, so students are less inhibited about acknowledging their unethical actions. All of which is to say – bad news.”

But from talking to numerous student leaders, administrators, faculty members and national research experts, there is a clear shift in the academic culture that is threatening to hollow out the Honor Code.

A Close Call

“It seemed easier to cheat, because cheating was more acceptable than a C-,” said Billy. “I was scared, coming into freshmen year and worried about my GPA and potential for the future.”

Since his close call in the first-year microeconomics course, Billy claimed he swore off the large-scale cheating. But he hasn’t been totally clean. When asked when the last time he cheated was, Billy sighed. He had a look like he was finding his footing into more honesty and before leaving self-preservation, but decided to sidestep the question entirely: “Well, the best way I can put it is that I’ve gotten a lot more self-conscious – well, not self-conscious – but I have a lot more integrity from the work,” he said. “But I couldn’t say that I haven’t glanced over a person’s test and taken an answer.”

“I am in something that genuinely feels like a passion and not in economics trying to get into a high-paying finance job,” he said. “Personally, I would take the lessons I learned and take them with me into the real world, but I could see how someone who, after having abided by the honor code for four years and then getting into the real world where there is no honor code, could get back into cheating in many ways.”

When asked whether every cheater gets what is coming to them, he let out a smile. “I don’t think so.”

Billy’s story is something of a failed morality tale, one driven by a desire to survive, scarred by the threat of losing everything, and changed — maybe only slightly — by the College’s culture of academic integrity central to the Honor Code. But whether he was changed by it, even he didn’t seem to know.

“After that experience, it was more about the integrity of the work. It’s a good feeling to know that I don’t need anyone else’s answer and I can accept it.”

By the end of our conversation, it was clear that he was scarred, but not transformed.

“I couldn’t promise you that if a person’s answer was right in front of me, and all I needed was just one more question, I wouldn’t say there’s a 100 percent chance that I wouldn’t look at that person’s paper,” he explained. “But I haven’t done that in a while. I wouldn’t say that I would never cheat on anything in my life.”

Here and Now

Associate Professor of History Amy Morsman was struck by the cynicism in academic integrity from students in the first-year seminar she taught last fall. She passed out an article about the recent cheating scandal at Harvard University, thinking this was a chance to impart to her students what life means with an Honor Code.

“I expected them to be shocked and outraged by this breach in ethics,” she said. “I was mystified by the sort of ho-hum response my first-year students gave.”

Some of her first-years embraced an attitude of “well, in the world of today, to get ahead you might have to do this,” Morsman recounted. “Some of my students already seemed so jaded by the world.”

As it stands, the Code requires students to report witnessed cheating. But students who fail to, face a punishment that even the Chair of the Student Honor Code Committee (SHCC) Alison Maxwell ’15 couldn’t articulate.

“I don’t know what the specific punishment is [for a witness who failed to report cheating], because it’s not common for the judicial board,” she said. “We can’t actually know when someone has broken the honor code in that way.”

All the assets that an Honor Code offers — an unique trust between student and professor, the freedom to take an exam without suspicion in the room — gets no play at Middlebury, if integrity is lost on students in that same room. This failure has sent the SHCC to reevaluate the sustainability of peer-proctored exams.

But the chronicity of cheating and rising number in cases of apprehended cheaters is not a sure-fire sign that the community’s morality is hemorrhaging red. Approximately one in four allegations, usually in the context of plagiarism, are cases, in which the students are confused, “the result of insufficient instruction on the part of the College, [but more likely] a failure on the part of the student to internalize that information,” according to Guttentag.

The flurry of information sharing has also led to more confusion where the Internet has colored gray an area in plagiarism. Constant information juggling obscures our original ideas from the ideas we read and, as a result, the lines on plagiarism blur.

“Notions of originality have transformed today, because things are so easily copy-able,” Film and Media Culture Professor and Academic Judicial Board (AJB) member Jason Mittell said. “So much of what people are reading are re-blogs of other people’s works or references to other people’s creativity — with or without citation. We live in a culture of quoting and of remix and reference.

“I think traditional citation guidelines are hard to wrap your head around if you’ve been brought up in this generation of — I don’t want to say loose standards, but different types of practices where citing is not relevant. Precise referencing or asking permission to quote someone just doesn’t make as much intuitive sense to many students today. And sometimes that doesn’t make sense to me either.”

And SGA President Rachel Liddell hinges on Mittell’s point about the clash of tradition and today. For her, the Honor Code has a different meaning when its tradition, over a breadth of time, is worked into today’s context, a state of academic honesty she is “dissatisfied with at Middlebury.”

“The Honor Code has a beautiful history, where students got together and worked really hard to write it and pass it,” she said. “We don’t own it anymore. And if we don’t want to own it, then we have to figure out what else we want to own.”

Dean of the College Shirley Collado, suggest that the pressure to succeed doesn’t happen in a vacuum.

“We’re seeing a trend not just in Middlebury but at a number of selective colleges – and I’ve talked to many colleagues around the country about this – that students are really feeling the pressure: what it’s going to be like to be part of a global job market and exceling and being an excellent student at Middlebury,” she said. “So I don’t know how much of a role that plays in stress or academic dishonesty. It’s a question I raise.”

Beyond the Bubble

But cheating is not a Middlebury-centric issue. In fact, cheating happens less in schools with an Honor Code, according to the research.

The College’s cheating statistic runs consistent with similar schools with honor codes like Duke University, which identified in 2006 that 29 percent of students admitted to unauthorized collaboration. But in larger schools without an honor code, like Harvard University, more than 40 percent of freshmen admitted to cheating on homework, according to a survey conducted by the The Harvard Crimson earlier this year.

“Schools with honor codes are better off,” said Donald McCabe, professor at the Rutgers Business School and leading researcher in cheating. “Overall, honor codes work reasonably well though not perfect. The smaller the community, like at Middlebury, the easier it is to do. It creates a sense of community in which students realize that when they cheat, they’re cheating their fellow classmates. Large schools like Penn State and Rutgers are trying to increase the level of integrity among students and finding it very difficult.”

But compare Middlebury to the University of California, Berkeley, with nearly 36,000 students, where there is more anonymity and less noticeable impact.

“Cheating is no big deal, because it happens all the time,” Jasmin Soltani, a chemical-engineering student at UC Berkeley said. “It is ridiculously easy at a school this big with understaffed faculty in test-taking rooms.”

When explained the intention behind the Honor Code — that there is supposed to be ethical temptation, Soltani was skeptical. [1]

“The kind of unproctored exams at Middlebury would not work at all in Cal. 500 students taking the same exam in an unsupervised room? That sounds like a joke,” she said. “The academic environment (at Cal) is very cut throat and people would not pass up a chance to get ahead of the curve.”

Other students offer a more nuanced take on the cheating culture at UC Berkeley.

“Honestly, I saw very little cheating during my four years at Cal,” said Emma Vadapalas, a history and economics major who graduated UC Berkeley this year in May. “Most of the instances I recall involve minor infractions, such as students copying problem sets from each other or getting a friend more versed in the material to do a problem set for them. I call these minor infractions because if caught cheating, the student would get a zero on the assignment but not flunk the class.”

McCabe warns against this kind of lowered standards that qualify cheating. “The number of general cheating have gone down, but at the same time, there are a number of students who dismiss low levels of cheating and feel okay justifying it. I see it as a danger,” a slippery slope toward rationalizing severe acts of cheating.

Unlike UC Berkeley, Middlebury’s judicial process reviews cheating cases by the case.

Even if the College does have a lower prevalence of cheating than its larger counterparts, Liddell said that especially at a small community, there is a real cost to dishonesty – and we all pay it.

“The truth is, if I were to cheat, I hurt myself, but I also hurt professors and my fellow students,” Liddell said. “If I were to cheat and I get a 98, and then the professor looks at you, who got an 82, and you look worse. Cheating of all forms damages all students.

The Future of the Honor Code

That does not mean improvements are not in order. But even with great strides taken to address problems of the Honor Code in last year’s review – the HCRC redesigned go/citations and developed field-specific responses to ethical dilemmas – this semester, nine professors are currently piloting Turnitin.com, a plagiarism detection service. After this semester’s trial run, there will be talk of Turnitin’s expansion, the implications of which could severely shake the trust built into the Honor Code.

But students and professors staked out different views on the introduction of Turnitin.com.

“The point of using Turnitin.com is not to catch and haul students into the AJB room on charges of plagiarism, but to fix the problem before it becomes a habit,” said Morsman, one of the nine professors experimenting with Turnitin.com.

“We do ask professors to check for plagiarism when they read our papers and Turnitin provides a more efficient method of the same process,” Liddell said. “But though not a violation of student rights, Turnitin is not congruent with the idea of the Honor Code, because it does not rely on trust and it does not rely on mutual respect.”

The introduction of Turnitin might be a prelude to the far greater changes the Honor Code could suffer if cheating continues.

Indeed, at a time when cheating reports are climbing, strides are being made to tackle the problem from all directions: top-down — through Turnitin — as well as ground-up. A main focus of the recently formed SHCC is to fix the system of peer proctoring, which Maxwell says is a broken part of the Honor Code.

“I feel like we are forcing students to break the honor code when we ask them to proctor each other,” Maxwell said. “Everyone we’ve talked to said ‘I will never tattle on a fellow student,’ so it’s very clear it doesn’t work. We’re coming up with a solution, but I don’t know how it’s going to turn out. Only time will tell.”

But Associate Professor of Economics Jessica Holmes, who teaches Economics of Sin, too, concedes that peer-proctoring empirically does not work, but offers a quick solution.

“The fix is simple: proctoring. It is too small of a community and no one wants to be viewed as the ‘rat.’ Proctoring [would] reduce both cheating and the pressure on students to report on each other,” she said. “How can I ensure the academic integrity of the exam environment if I am not in the room?”

But even professors who have not brought students up on charges are aware of the shifts.

“I’ve been teaching here for 12 years and I’ve never brought a student up on charges,” Morsman said. “But I hear about cheating more from students and I hear it more from staff and the people bringing cases to the judicial board. I’m aware that it exists, that it’s getting worse, and the College is responding to it.”

Members of the community are slowly backing away from the original vision of the Honor Code. Doubtless, students and professors hope to see the Honor Code hold its own in an increasingly competitive society and succeed. But there are signs that things are about to be different. In the midst of the decisive failure of peer proctoring, the formation of the SHCC and the fortification of preventative measures like Turnitin, it is entirely possible that perhaps a decade from now will look entirely different — a proctor in every exam room and a website reading each paper.

[1] With regard to this article's definition of the Honor Code: "When explained the intention behind the Honor Code — that there is supposed to be ethical temptation, Soltani was skeptical" was adapted not from the Middlebury Handbook, but from a New York Times piece about the general Honor Code: "The intention of honor codes is to generate the very situation you describe as precarious: they’re supposed to create ethical temptation."

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this article, as well as that in print, quoted Professor of Media Studies Jason Mittell of saying, "Precise referencing or asking permission to quote someone just doesn’t make intuitive sense to students today. And it doesn’t make sense to me either sometimes.” There was a missing qualifying statement; it should be "Precise referencing or asking permission to quote someone just doesn't make as much intuitive sense to students today."

Cheating: Hardly A Secret

Comments