Last week, on Thursday, Nov. 7 the College admissions office began formally reviewing early decision applications, which Dean of Admission Greg Buckles projected would be around 691 applications. This year, however, admissions is hoping to reduce the class size from 600-610 to 575 students for September admits and from 90-100 to 80-90 students for February admits, making an already competitive process even more competitive.

“The goal is to reduce the stress on crowded first-year housing overall,” Buckles said.

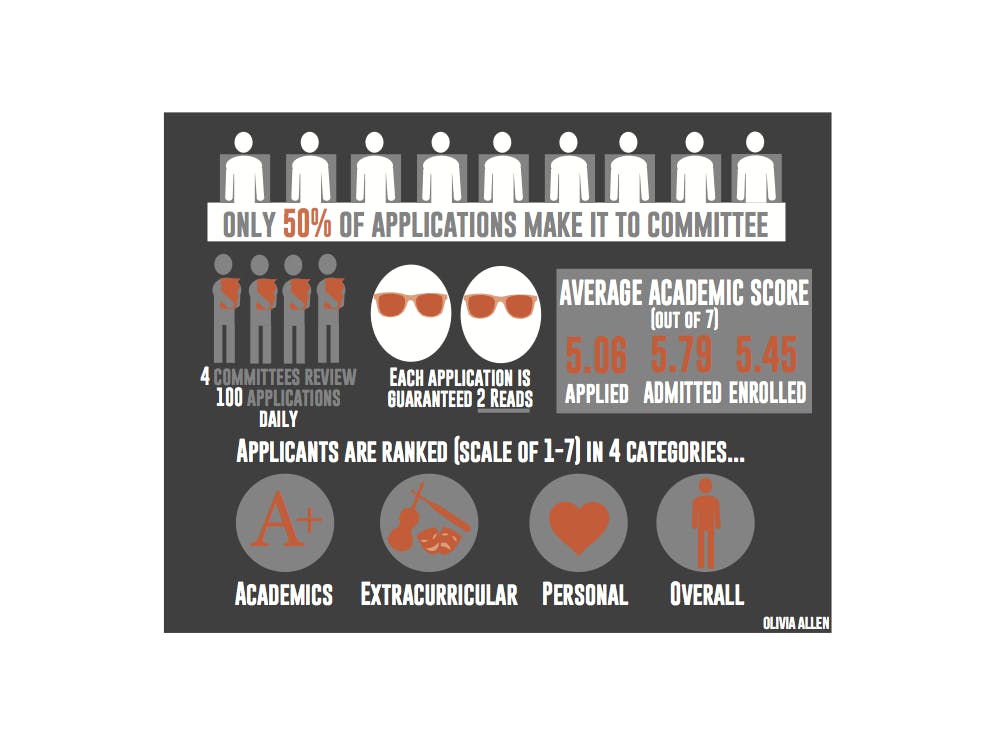

Each year, like those 691 applicants, high school seniors all over the country apply to college and admission counselors seek an efficient, fair way to sift through the extremely high number of applications. The College receives around 9,000 applications each year — last year that number peaked at 9,109 — and employs 13 full time readers, four seasonal readers and four operational staff members to review those applications.

Therefore, each admission cycle counselors grapple with making difficult decisions and making those decisions in an efficient, fair manner. Although this challenge is not unique to the College, the system it uses may be unique. Every admission office has a different method of choosing the incoming class and sifting through what will ultimately be acceptances and rejections. This system is a necessary evil, a formula, to make informed choices and predictions on how a student would perform on this campus.

“It’s a sifting a method,” Buckles said. “We are constantly sifting through a pool of applicants so that students begin to rise through the process, so to speak.”

At the College, the first part of this sifting process is the first read. Every application that comes through the office is read twice. The first read is usually completed by the regional representative; each counselor covers a few states or countries based on the location of the applicant’s high school. The second reader is usually chosen at random.

The two readers rank students in four categories: academic strength, extracurricular contribution and personal qualities on a 1-7 point scale. An overall score, the forth category, is then attributed to each applicant, which is not an average of the three categories, but is a recommendation.

“[The overall category] is a recommendation or a general sense of what the reader is recommending for a decision,” Buckles said.

According to the admissions office, the first, most important category is the academic rating of an applicant. This category looks at a student’s transcript, while taking into consideration the high school’s rating system and curriculum. Supporting materials such as the school report, letters of recommendation, testing scores, grades and personal essays are considered within this category as well. All those combined assigns an academic rating.

The rubric for the academic category, which reads, “To what extent does the applicant demonstrate intellectual achievement, engagement, and potential for academic success at Middlebury?” is the overarching question by which each reader attempts to apply a rating.

For this first-year class, the average academic rating, out of 7, for all students who applied was between 5.06 and 5.76 for admitted students. The average academic rating of students who enrolled was 5.45.

The next category, the extracurricular rating, which is also on a 1-7 scale, asks the reader, “What level of contribution will this student make outside the classroom taking into account skill level, initiative, and leadership capabilities?”

A seven in this category would suggest “an unusual and rare ability to contribute here at a national level talent,” while a one rating suggests “no foreseen involvement on campus.” Athletics, art and music would all be considered here.

The personal category which Buckles calls “the most illusive, and the most subjective” seeks to answer the question, “How will the Middlebury community be impacted by this student’s personal qualities?” with a 7 suggesting “exceptional potential to positively impact the lives of others.”

“[The personal category] is one we talk a lot about because it’s a hard one to know,” Associate Dean of Admissions and Head of Diversity Recruitment Manuel Carballo said. “We aren’t interviewing students or having conversations with them. But personal qualities are, to us, is this person going to be a good roommate or a good person to talk to?”

The last category, the overall category, asks, “considering the applicant’s overall contribution to campus including academic talent, extracurricular talent, personal qualities, and special considerations, what recommendation would you give to the committee?”

The overall category is where any special considerations are taken into account, including legacy status, first generation college student status or a set of extenuating circumstances.

Then, based off of the readers’ numerical evaluation of applications in the listed categories, applicants move into committee session where formal decisions are made. On average, only 50 percent of applicants make it to the committee session.

“The first reader may determine that a student is unlikely to be admitted,” Buckles said. “Then a senior, more experienced counselor will go back and verify that [not going to committee] is in fact the right decision and that all things being equal that person will not make it to committee.”

If it has been determined by the first two readers that a student should go to committee, then students are assigned to a committee group. During the regular decision cycle, the office has four different committee groups working at once, comprised of four to five people who get through about 100 decisions a day.

As committees begin reviewing applicants, one of the two readers usually presents the applicant to the committee, and each counselor gets one vote to either admit, deny or waitlist the student.

“I call this precision guesswork. We are trying to apply consistent, fair, ethical, human, educational standards and applications to what is a very subjective, dynamic process. We are trying to make good decisions about 17-year-olds.”

Any decision that cannot be made easily or that the smaller committee is not positive about are passed off to a full committee session which is usually held for a week at the end of the decision process. Both Buckles and Carballo noted that they almost always have to trim the class during this portion, noting how difficult that process can be.

“To me, the hardest part of the process is students come in from such different backgrounds — educational backgrounds, family backgrounds — that there is no way to equate things,” Carballo said. “So how do you compare them? How do you compare students from schools who have a library just like ours to school that don’t have one. It’s not a choice. We have to put them in the same pool and make some decision.”

Read a response by the Alumni Admissions Programs.