The Middlebury Campus sat down with College President Ronald D. Liebowitz to discuss his time at the College. The conversation ranged from when he first became President to some of the changes he has seen at the College in the past years. Liebowitz will depart the College at the conclusion of the school year.

Middlebury Campus (MC): What was it like moving from a role as a Professor at the College to an administrator (specifically Provost and Executive Vice President), and then to the College President? What was it like, as someone within the College, stepping up to become College President?

Ronald D. Liebowitz (RL): Like many things, it had its advantages and disadvantages. In my particular case, I was a tenured member of the faculty, which means I went through the tenure process and then I served in two major academic positions before becoming president — the dean of the faculty and then provost. Having had these opportunities, I was able to learn a lot about the institution, seeing things from many angles, and working with major committees along the way, all of which was so very valuable and a real advantage for me.

The disadvantage coming “from inside” the institution is that, having had to make some tough decisions, sore feelings sometimes linger. When you come into the presidency with a history, you face some additional challenges when trying to move the institution forward. So, there are pluses and minuses to both, but I feel very fortunate to have known the institution as well as I did when I began my term as president.

MC: And I think a lot of people forget that it has only happened three times in the College’s history.

RL: Yes, I like to remind people who are not knowledgeable of Middlebury’s history that the college has had a president from within three times in 214 years – once in the 19th century with Ezra Brainerd, once in the 20th century with John McCardell and me in the 21st century, so maybe that means we can expect outside presidents for the next 85 years!

MC: Do you think your background as a specialist in political geography influenced the projects that you have embarked on during your time as President? Examples include new schools abroad, new language programs, and Monterey.

RL: I have never given this much thought. I think my background as a Russianist and also as a political geographer had some impact but I would like to think that most academics today, regardless of one’s discipline, would see the changing world in which we live and how that relates to the type of education that our students need and by which they would be best served. I would hope that most academics would see the direction we’ve taken as complementary rather than in competition with a traditional liberal arts education and reflects the changes external to Middlebury and higher education in a smart and beneficial (to our students) way.

MC: Where do you hope to see Middlebury’s relationship with Monterey go in the next decade or so?

RL: I’ve been fairly consistent about this since 2005 – I don’t believe that programmatic (academic) integration can and should be forced where it does not make sense. The great attraction of Monterey was that, while Middlebury and Monterey shared an underlying commitment to linguistic and cultural competency, it was such a different institution from our undergraduate liberal arts college. The differences open up many opportunities for students to engage in courses and programs, plus meaningful engagement with MIIS faculty, whose philosophy about cultural competency is similar to our faculty’s, but whose curricular content and pedagogy are so different from what our students have here on campus. We are not a professional, graduate school – we’re not even a pre-professional undergraduate school! We are a liberal arts college – and the juxtaposition and the complementarity of these two is powerful for those students interested in international careers.

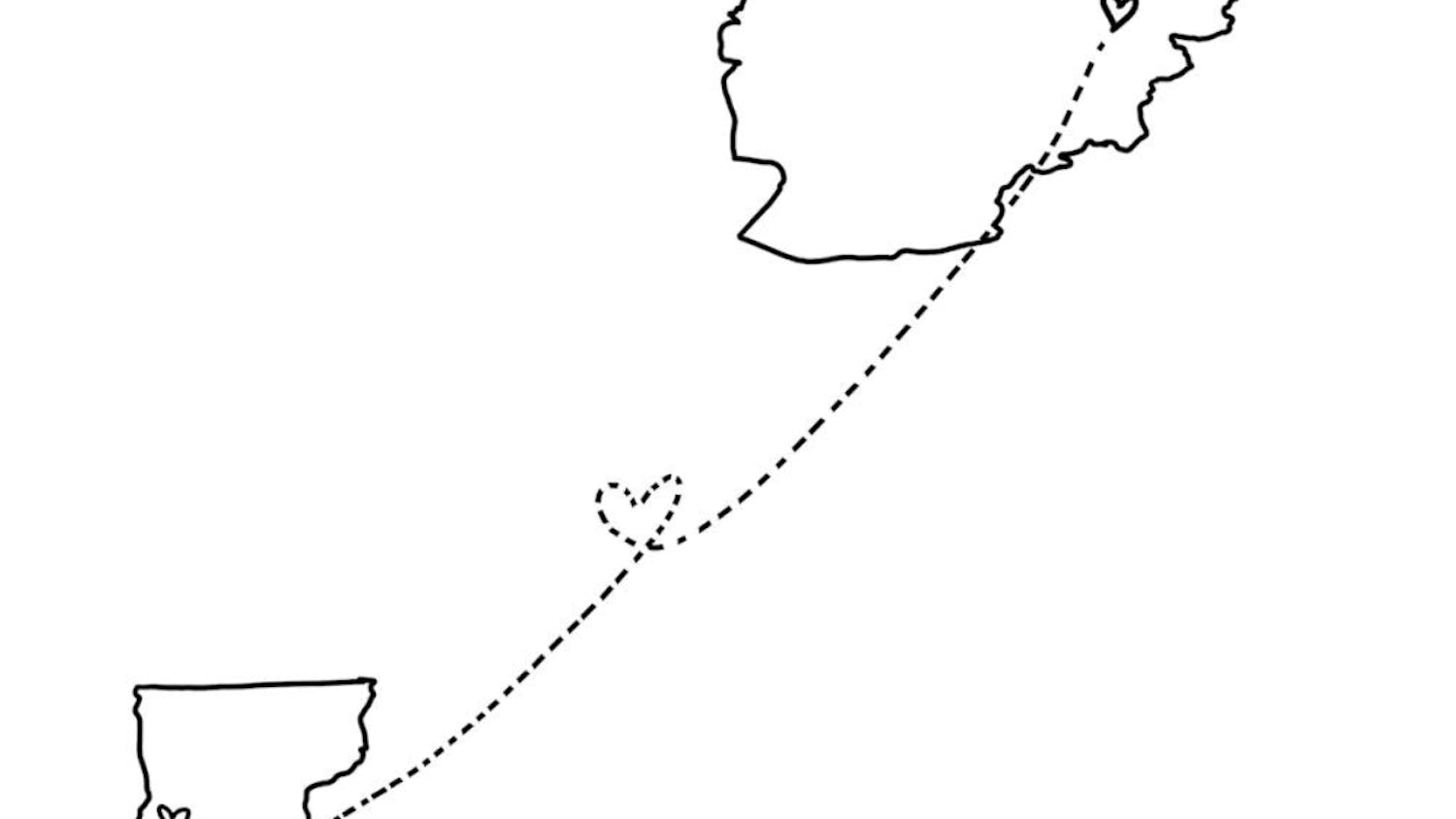

That said, Monterey and its programs are not for everyone. They are intended to be for those students who want to pursue international-related careers. But beyond the obvious complementary curricular opportunities, there is another benefit that comes from the collaboration: the strengthening of the “Middlebury” network. About 30-35 percent of Monterey students are international students (the majority from Asia), and most graduates go on to work all over the world. By expanding our alumni network to include Monterey alumni, faculty, and staff, we strengthen the Middlebury network, which helps current students and recent graduates by opening doors to internships, employment opportunities, and meaningful connections across the globe. This is an often overlooked benefit of our relationship with Monterey. My hope, then, would be that students take advantage of the opportunities to combine a professional international education offered at Monterey with their undergraduate traditional liberal arts experience to the benefit of their post-college plans; that they would use the resources that Monterey offers for both advanced degrees and a robust, international-oriented network.

MC: On the topic of the undergraduate experience, in the time that you’ve been here, how do you think the student body has changed? Have you seen changes in the typical Middlebury student?

RL: The student body has changed over thirty years, yet the influence of the institution itself on each generation of students remains stronger than any specific change I might highlight. One example: a characteristic of the student body that I noticed immediately upon arriving at the College is that students are incredibly civil towards one another. We have disagreements, altercations, and skirmishes for sure. Yet, the culture here is very forgiving to individuals who in other environments would face far greater challenges. I suspect this is because the student body as a whole recognizes that over their four years here each member of the larger community is going to rely primarily on the 2,450 other undergraduates for one’s intellectual, social, and cultural sustenance. On campuses in urban areas or at institutions with a graduate population, this might not be the case; the environment is different. Here, though, the undergraduate experience is not diluted, it’s a close-knit community, and this cultural aspect has remained a constant and has been present for a very long time. It is something that first-years learn early on so by the time they are sophomores, juniors, and seniors, they themselves pass this on to incoming first-years.

There’s a flipside to this characteristic of the Middlebury culture. Although ours is a very smart student body, many faculty see less “mixing it up” intellectually in class than one might find at a Columbia, a Harvard, a Yale, or a Wesleyan – places located in more urban environments. If this is true, I believe it’s a fair trade-off. I think without the cultural characteristic of students being civil toward one another, less competitive, more supportive, and more collaborative, a lot would be lost here in terms of the overall quality of the educational experience for students.

But to your question, what has changed? The student body has become a lot more socioeconomically, culturally, racially, and ethnically diverse. Though we strive for greater diversity still, those of us who have been here a long time see great changes on this front. When I first got here, about 1 in 20 students were American students of color or international; now, that ratio is greater than 1 in 3. That’s a huge change. We know that a more diverse student body translates into a richer educational experience as a result of students sharing different perspectives and life experiences both inside and outside the classroom.

Other changes: students today are obviously more conversant with technology. They are more apt to volunteer not only in town, but across the country (alternative break service trips) and across the globe. And many of my colleagues report students are more visibly focused on jobs and employment, which is understandable given the changed financial circumstances they face at graduation than 30 years ago. So there has been change, yet the overall dynamic of the student body – being supportive of one another, collaborative, and open-minded – remains and still is the general feel one gets here.

MC: I want to talk a little bit about the carbon neutrality initiative, the Franklin Environmental Center and the Solar Decathlon entries as examples of how Middlebury has become an environmental leader in the past 10 years. Is there one achievement that stands out to you from all those?

RL: No, not really. In the last 10 or 11 years during my time as president, a number of notable things have occurred and the spotlight should be on the students; in almost every case the students have been at the center of these initiatives.

The whole idea of carbon neutrality at Middlebury didn’t start with the administration and it didn’t start with the Board of Trustees; it started with a student back in the 1990s who shared his work from a senior seminar and passed it on to younger students interested in climate change and environmental stewardship. About a decade later, when the Sunday Night Group formed, students in that group were the ones who brought forward the proposal for the institution to reduce its carbon footprint and eventually to pursue carbon neutrality. Some Middlebury faculty worked with students to fine-tune their pitch to the administration and eventually to the Board of Trustees. Their presentation was excellent: they admitted when they couldn’t answer a question and pledged to get the answer to the Trustees later (and they did); they had a deep command of the issues; and succeeded in getting the trustees to adopt their resolution, which was never a foregone conclusion. Seven years later, with the coming implementation of our bio-methane initiative, we are almost there – becoming carbon neutral without purchasing any offsets.

For the Solar Decathlon, the idea was first proposed by my wife, Jessica, and with the guidance of faculty and staff in the sciences and environmental studies, the students more or less took over the project. The institutional commitment was significant to support the effort, though the rest was on the students, and they showed remarkable maturity in overcoming some real challenges that they had never encountered in their traditional liberal arts education. It was not just about the academic challenge or learning about solar power, renewable energy, engineering, and more; it was also a huge challenge of working together as a team, respecting one another, accepting opposing views, and compromising on so much along the way. We don’t have a graduate program in engineering, or even an undergraduate engineering program. Nor do we have a graduate school of architecture, and so the students had to rise to the occasion to learn things on the fly and they did. Yes, they were mentored by faculty and staff in a significant way, but they needed to use their skills and knowledge gotten in the classroom to draw on the expertise from around the state of Vermont to help them as well.

If you go through almost every environmental initiative over the last 20 years – the start of recycling, the establishment of our composting program, sustainability initiatives, biomass gasification, carbon neutrality, real food, plus others – most have been student-led or the idea was student generated. I think that’s the key thing that we should take away and really applaud: that the institution is a leader in sustainability, but that wouldn’t be the case without the students.

MC: When you stepped into the role of College President in 2004, did you think about what you wanted your legacy to be when you eventually depart?

RL: I think almost every President probably steps in saying, “If I could leave the institution in a stronger position upon departing than when I began, I’ve done well.” All the more when one inherits an institution of the quality and stature of a Middlebury. I think what has made these last 10-11 years so interesting has been our need to recognize, for really the first time in many decades, the external forces that have created some great challenges for higher education, including Middlebury. If I would have been told in 2004-05 that we would face the worst recession in a century just 3-4 years later, I would have said, “Wow, what are we going to do?” You don’t plan on such an occurrence – higher education financial models seem to show variables all moving in the positive direction, year after year, and fail to include stress tests or “worst case scenarios.” And, there is no blueprint or plan sitting in a desk drawer in the president’s office awaiting you when an issue of this magnitude arises.

It is easy to ignore the external pressures mounting on higher education and continue with a “business as usual” approach to operations, but such an approach will no longer do. I believe getting some tough issues on the table for discussion and action, no matter how much people wish to ignore them, is an important part of the past 10 years.

MC: On the subject of the recession in 2008, can you talk about what it meant to manage that crisis?

RL: The most challenging thing about the recession was that we didn’t know when it might end. We needed to judge and judge early, the level of cuts we would need to make in order to address what we had estimated would be $30 million 4-5 years out, yet it could also have been worse: we just did not know. Since compensation amounts to roughly half the institution’s budget, it was clear the only way to make real headway into a projected deficit would be to address staffing. But when you make a decision to reduce staffing through layoffs, it can be devastating to a small community if it is not handled well and with great sensitivity. Though we knew we needed to reduce staffing, we didn’t know how many jobs needed to be cut.

In the end, I thought the institution – faculty, staff, students, administrators, alumni, trustees – did a remarkable job because we were one of the first schools, if not the first school, to engage our community, letting them know that it was likely we would need to begin a process to determine how best to address the economic crisis. We didn’t have any specific answers or recommendations, of course, but we tried to prepare the community for a process that would result in significant cuts. The challenge at that early date was the unkown: how much would our endowment drop? How would our students’ families be affected? How many people’s financial situation would change? So the greatest issue was the unknown - not knowing when the crisis would end.

I think back to the changes the recession brought to other institutions and I am grateful we were able to preserve what our students, faculty, staff and alumni told us was most important to them for us to preserve. Though there were some differences among the priorities for each group, everyone emphasized that we needed to avoid involuntary layoffs: that was the biggest concern among all the groups. As a result, we offered voluntary and early retirement programs for staff and faculty through which medical coverage continued until age 65 and individuals received payments that provided security and were based on years of service. Between 2009 and 2011 about 110 staff positions were eliminated through these programs, and 12 faculty colleagues chose to retire early. We also reduced services at Atwater (no meal-plan dinners and only a continental breakfast); reduced significantly catering options for departments; reduced some budgets between 5 percent and 10 percent; froze salaries except for the lower end of the pay scale; and increased the size of our student body by 50 to provide more revenue to make up for the endowment decline.

However, the alternatives to our major cutbacks were severe. Some peer institutions ended need-blind admissions, others had to delay library and science center projects, and still others cut faculty positions. We didn’t freeze the size of the faculty and in fact added 11 new faculty positions as was planned, we had no involuntary layoffs. We did not sacrifice the excellence of our academic program.

Moving early and decisively, having feedback from so many constituencies through the extensive surveys, and being able to focus on what was most important to each of the groups helped us to come out of the recession as well as we could have hoped.

MC: Are there other difficult choices that you had to make in your time here that come to mind?

RL: There have been a number of challenging or difficult choices surrounding policies, but that is to be expected. The Monterey opportunity, allowing military recruitment on campus, accepting a gift to create the (Chief Justice) Rehnquist endowed professorship, and establishing Middlebury Interactive Languages stand out. All of these represented contested issues, and a lot of the differences in opinion, in my view, stemmed from the different time horizons that a president and board must take when considering opportunities and institutional direction. Students, faculty, and staff, if I can generalize, tend to view things in the shorter-term – those things relevant to a student’s four years here, or for faculty and staff what is related to the here and now or to one’s career. A president and Board must look beyond that time horizon to project what is in the best interest of the institution long term. Some disagreements are rooted in true philosophical differences (e.g., “what is the relationship between a liberal arts education and our students’ finding jobs after graduation?”), yet I would say there is greater agreement than there are difficult and contentious debates. The difficult issues, however, bring out passion and sometimes anger, and sometimes overshadow all that we do agree on as an institution.