The end of this year’s whirlwind J-term brought in the highly-anticipated Ragtime musical, a co-production by Town Hall Theater (THT) and the Middlebury College Department of Music. Dealing with the turmoil, tensions and triumphs of early twentieth-century America, Ragtime follows the lives of Harlem musician Coalhouse Walker Jr., played by Steven Kasparek ’16, a white upper-class family in New Rochelle, New York, and Tateh, a Jewish immigrant, played by Jack DesBois ’15, who leaves Latvia to make a life for himself and his young daughter in the Lower East Side. The cast performed to sold-out audiences at THT every night from Jan. 22 to 26.

As per J-term musical tradition, the entire production was put together during intensive rehearsals over a span of three weeks. The cast came in knowing all the music and lines, but worked long hours to build the set and piece the entire 38-number show together. Likewise, the orchestra had only two weeks to rehearse the score.

Of the 33 actors, some were experiencing their first taste of theater, others were seasoned members of the department and four were hired professionals.

“In order to do Ragtime properly, you really need to balance the three ensembles, and we didn’t get enough for a turnout for the African-American Harlem ensemble, so we had to hire out some people,” stage manager Alex Williamson ’17 said.

Despite the wide range of acting experience within the cast, Ragtime proved to be a seamless and vibrant production, particularly through its smooth transitions and careful choreography. Leaving no more than ten or so seconds between acts, the cast expertly navigated the stage to create scenes of drastically different setups – from the slums of New York to a baseball stadium to a lush Victorian estate.

“Since Ragtime is all musical numbers, it’s important for it to flow like a dance,” Williamson said. “One thing leads nicely into another.”

A flurry of changing developments within the United States marks the first act of the play. Riots against the ravages of American capitalism pop up across the country, waves of immigrants arrive at Ellis Island with hope in their hearts and nothing but the clothes on their backs and many white Americans with long-established roots in the United States grapple with their growing distaste toward all outsiders. Indeed, the wealthy residents of New Rochelle reminisce joyously in the opening number of the musical, singing, “Ladies with parasols/Fellows with tennis balls/There were no negroes/And there were no immigrants,” only to be interrupted by the shouts of Eastern Europeans boarding a ship for Ellis Island.

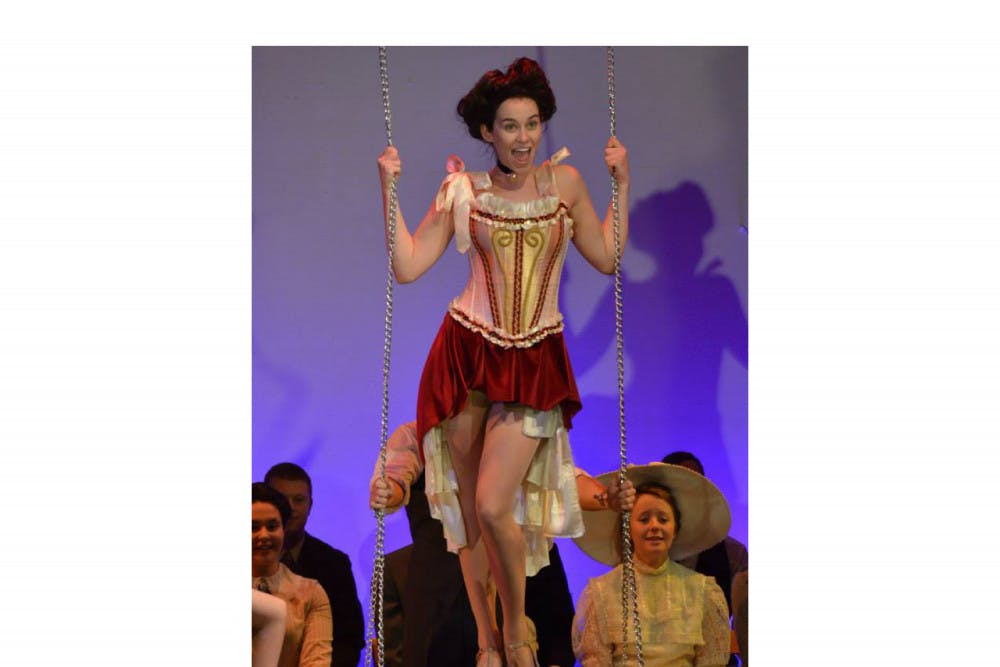

From a meticulously-built Model T car prop to the appearance of legendary stunt artist Harry Houdini, played by David Fine ’17, the musical was filled with historical references that set a rich context for the three interlinking narratives of Tateh, Coalhouse and the wealthy white family. This traditional household is headed by the doting Mother, performed by Hannah Johnston ’15.5 and the strong-willed Father, played by Michael McCann ’15. The role of Evelyn Nesbit, the dazzling, real-life vaudeville personality, played brilliantly by Caitlin Duffy ’15.5, further contributed to the realism of the production. Her flamboyant ways and extravagant, shimmering costumes served as a delightful tribute to popular entertainment of the times.

During Act I, Mother discovers an abandoned Negro baby in the front yard of their Victorian estate, and decides to provide refuge for both him and the mother, Sarah, played by professional Diana Thompson. The story escalates quickly from there, as Sarah’s ex-lover, Coalhouse, attempts to court her, eventually wins her over and then tragically loses her when she is beaten to death at a campaign rally in New Rochelle. Her death leaves him a bitter and angry man. As a result, Act II carries a much darker tone, with Coalhouse seeking to find justice within a radically flawed social system. Meanwhile, the growing rift between Mother and Father, who don’t see eye to eye on the racially-charged turmoil of the times, as well as the rising success of the exuberant and hardworking Tateh offer alternative perspectives on the multi-faceted, fast-paced nature of 1920s America.

Amidst the heavy material of the play, Little Boy, the young son of the white upper-class family, provides a refreshing and innocent presence. Portrayed by Emilie Seavey ’18, who donned a cap over her short blonde hair, Little Boy easily breaks the tension in the room when Coalhouse comes to the family’s posh house in search of his ex-lover, Sarah.

“This is Sarah’s baby,” Little Boy tells him, gesturing toward a crib in the corner. He then asks brightly, “You want a cookie?” — an absurdly innocent inquiry that drew laughs from the crowd. His childish obliviousness and endearing eagerness help to lighten the mood in scenes that brim with tension, fear and uncertainty.

Alongside astounding vocals by the entire cast, the visual effects of the production added a lavish charm that appealed greatly to the audience. One particularly awe-inspiring display featured Tateh flipping through a book of moving sketches with his daughter. As they gaze at the pages, a woman, played by Duffy, dances gracefully behind a transparent curtain at the back of the stage. Strobe lights flash upon her flowing figure, creating choppy movements that gorgeously mimic the effect of paging through a continuous sequence of sketches.

Meanwhile, the upper-class white family — particularly the females — don extravagant clothing that beautifully reflects the fashions of the times, from skirts that flared out at the bottom to high lace collars to pigeon-breasted blouses. Only one element was missing — most women of money wore dresses with lace trains; but seeing as such extensive costumes likely would’ve caused the actresses to stumble onstage, costume designer Annie Ulrich ’13 added ruffles at the bottoms of their dresses instead. Nevertheless, the juxtaposition between the upper-class family’s fancy white outfits — complete with delicate parasols and thin lace gloves — and the immigrants’ dark, tattered rags created a striking visual display of privilege and disparity.

Despite the old-fashioned outfits and radically different culture of ragtime and vaudeville entertainment, the timeless themes of race, oppression and injustice that underlie this stunning musical resonated deeply with the Middlebury community.

“This play is incredibly pertinent to the current atmosphere and the events that happened in the fall, between Ferguson and the New York cases of police brutality,” Ulrich said. “Racism is on everyone’s mind these days.”

Though the final scenes were scattered with tragedy, the story ultimately ended on a heartwarming note, ringing with messages of optimism and new beginnings. Connor Pisano ’17, who played the crotchety, racist grandfather of the upper-class family, encapsulated the juxtapositions inherent in the piece.

“The original author wrote the play for a Broadway audience,” Pisano said. “People go to the theater for an uplifting message or some kind of hope. But [Ragtime] is too tragic for most of the show to have some kind of random happy ending.”

Indeed, there’s no denying that in all of its lavish charm, the musical was strategically marketed to a broad audience. The sweeping score and poignant performances of the Middlebury production are bound to linger in the minds of anyone who was lucky enough to experience this magnificent feat of artistry. And ultimately, whether or not the epilogue accurately reflects the nature of reality, Ragtime serves as not only a rich insight on America’s troubled past but also a meaningful outlook on the turbulence that has continued into modern times.

THT Thrills with Timeless Themes

Comments