What does it mean to combine laughter and healing? To be the “perfect” survivor? And what do clowns and “panda puppies” have anything to do with it? Trying to explain the Post Traumatic Super Delightful (PTSD) play to those who did not watch the show was challenging at best. Performed in Hepburn Zoo on Thursday, May 5, Post Traumatic Super Delightful is most simply described as a one-woman show about a community trying to heal after a sexual assault. In practice, it is a heartbreaking, hilarious and nuanced tale of survivors, perpetrators and bystanders – and the impacts of a system that has not done anyone any favors.

Post Traumatic Super Delightful is written and performed by Antonia Lassar, directed by Angela Dumlao, stage-managed by Olivia Hull and further supported by a large team of women with varying backgrounds and skill sets. The fictionalized content stems from interviews with survivors, perpetrators, administrators, faculty and staff within the judicial system, and contains only two moments from Lassar’s real life. Director of Health and Wellness Education Barbara McCall, Molly McShane ’16 and Rebecca Coates-Finke ’16.5 worked to bring the play to campus through the Department of Justice Grant.

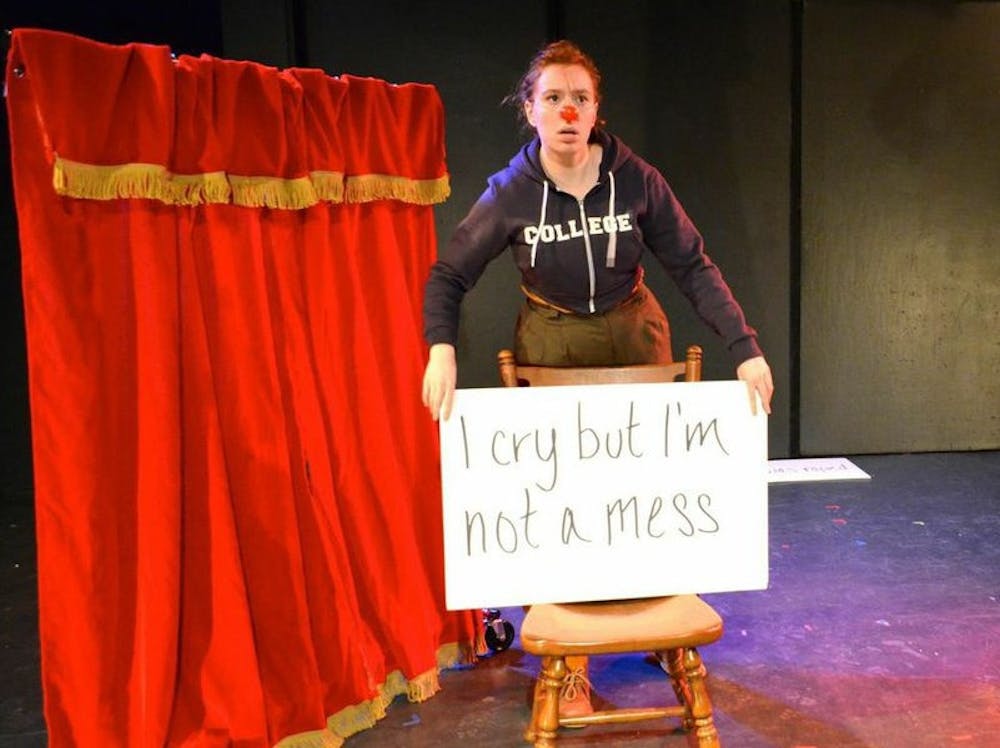

First, we meet the clown – a woman dressed in typical clothing who dons a red nose and performs ridiculous antics against the backdrop of voiceovers and music. Each interlude featuring this nameless, smiling character is infused with humor and stark realizations. At one point, the clown walks out with a pile of placards and begins to dance to the pulsing beat of “Survivor” by Destiny’s Child. One by one, she shows the front side of each placard: “I’m pretty.” “I’m white.” “I’m a girl.” “I’m the perfect survivor.” (She pauses after “I’m white” to show off her most awkward and invigorating dance move yet, before pointing to the sign again in a hilarious, self-deprecating recognition of her own whiteness.) Flipping the cards to the opposite side, she continues: “I’m not like the angry ones.” “I cry but I’m not a mess.” “I hate my rapist.” “None of you know him so none of you doubt me.” “I’m also perfect.” “At rolling my tongue.”

The clown proceeds to roll her tongue repeatedly with impressive dexterity, causing the audience to laugh in bewilderment. The contrast between this hysterical demonstration and the difficult truths conveyed by the placards is strategic and intentional. Society has constructed the narrative of the “perfect survivor” of sexual assault – white, female, pretty and not too teary-eyed, among other characteristics – to the detriment of anyone who does not fit this elusive mold. The clown highlights these identity politics by presenting the situation in the most straightforward manner possible.

“The play takes the trauma and pain that may be associated with being a survivor and doesn’t try to define it, which is the purpose of the clown,” Coates-Finke explained. “It’s responding to the myth of the perfect survivor, the narrative of what one should do and how one should be. The clown takes away identity in some ways, and just gives space.”

Lassar, who drew on her own training as a clown to create Post Traumatic Super Delightful, sees great potential in healing through laughter.

“Clowning has been used in sacred rituals in some cultural contexts. The sacred clown can be a presence that reflects back the truth of the community to the community, and mimics what you are doing,” she said. “The laughter is a recognition that we do act like that, people do talk that way. Getting a group of people to laugh about anything is to acknowledge that it exists. This is very powerful in a society that often invalidates survivors’ experiences.”

Though Post Traumatic Super Delightful was written largely for and by survivors, “Julia” – the fictional college student who was sexually assaulted by “Bryan” – never makes an appearance. Instead, her name comes up only in heated conversations featuring Lina, the school’s Title IX Coordinator, faculty member Dr. Margaret Roach and Bryan himself. Because it is a one-woman show, however, these conversations are enacted in a one-sided manner by the ever-evolving actress Lassar. Responses are implied rather than uttered aloud – and due to prominent changes in vocal and physical expressions, there is never a doubt as to which character is speaking at any given moment.

Lina uses brash language cloaked in a thick Russian accent, with inflammatory statements such as, “But I push her [Julia]! You know, I can file complaint myself, but if she won’t let me use her name, it won’t go anywhere. I’m not upset. I am upset. I shouldn’t be upset, but this is my first case. I want justice!” In contrast, Margaret speaks with a stiff, high-strung formality, while Bryan’s light Texan drawl marks all of his confused, frustrated and painfully honest musings.

In featuring a variety of voices, Post Traumatic Super Delightful is a reflection of how sexual assault is perceived by – and therefore affects – an entire community.

“Instead of hearing a story from a very singular perspective – which is a really important perspective of a survivor, but which can be limiting in terms of a full understanding of sexual assault and the ripple effect – we get a context and a way to process the pain,” Coates-Finke said.

“It allows us to think bigger about what the possibilities for awareness and activism are – the way that sexual assault affects people beyond the two or more people involved in one encounter,” McShane added. “It’s exciting both for people who are new to this conversation and for people who have been having this conversation for a long time.”

Through the dialogue, the audience becomes aware of the ways in which harmful narratives are reproduced.

“Bryan is not capable of rape. He is not a monster,” Margaret, his faculty advisor, says at one point.

“Julia does not look like a rape victim, okay? I had her in class. I know her.”

In response to the question “Do you think she was making it up?” Margaret states, “When you’re a drinker, there’s always the possibility you misremembered.”

Bryan’s pain and misconceptions also come to light through his interactions with Lina, the Title IX Coordinator who is adamantly advocating for Julia.

“I’m a freaking 21-year-old-boy! I’m going to have sex!” Bryan exclaims. “Rape is about power, it’s not about sex. What if this was just about sex?”

“I knew a guy in high school who got raped, real raped. And it’s really different. It’s like, I mean, he was bleeding. It was like on a walk home from a bar, and someone just appeared on the street. That’s rape. When you have to fight.”

Faced with these faulty assumptions – that drunk sex does not ever count as rape, that only monsters are capable of rape and that rape victims must look and act a certain way – it becomes clear why sexual assault has become such a blurry and complicated issue, particularly on college campuses. Post Traumatic Super Delightful addresses this complexity partly by stating these misconceptions aloud in the first place, and partly by emphasizing the humanness inherent in everyone involved.

For instance, though Lina demonstrates care and compassion, she is not always great at her job. She pressures Julia to file a Title IX complaint in the name of “justice,” but then realizes, “What is point of justice, if survivor will still be hurt?”

Meanwhile, Bryan is an accused perpetrator – yet his goofy demeanor and adoration for baby animal videos defy the common expectation that rapists cannot possibly be human. According to an anonymous feedback form submitted by an audience member, “It was tough to watch/hear from the perpetrator, because he was so nice… Ugh. I guess it’s easier to think of perpetrators as horrible evil people.”

Amid the stress of the judicial process, Bryan explains that all he can handle at this point is watching videos of “panda puppies” – a confession that drew huge, perhaps empathetic laughs from the crowd. Combined with his genuine, pleading questions – “I don’t know what I did! How could you not know if you raped someone? What’s non-consensual? What’s consensual?” – Bryan’s confusion becomes obvious. And in some ways, his actions become understandable. Like everyone else, Bryan is the product of a system, his thoughts shaped by a flawed education and harmful media messaging. All of these factors have led him to misunderstand what it takes to hurt another individual, or what it means to be a “good” or a “bad” person.

If certain lines from the play resonated with you in a strange or uncomfortable way, it may help to remember that we are all products of a system. Through our words, actions and willingness to listen to those around us, however, we can all play a part in dismantling rape culture.

“Even if you think you don’t know a survivor and you think you don’t know a perpetrator, everyone is so connected and complicit and responsible and in a positon to do something about sexual violence,” Coates-Finke said, “because you definitely know a survivor and you definitely know a perpetrator on this campus. Especially on one as small as ours.”

The multifaceted characterization within Post Traumatic Super Delightful proves that nothing and no one exists in black-and-white terms. Through its nuanced telling, the story becomes more real, and thus more relatable. Above all, it shows that laughter can, indeed, serve as an unexpected catalyst for healing.

Perhaps the anonymous feedback from the audience phrased it best: “I am feeling heavy and light simultaneously,” a 21-year-old female stated. “Trauma and sexual assault is not an easy topic to face, but I feel the load is always a bit lighter with the aid of the community and new tools.”

“As a survivor, I thought it was healing to see this performed in a serious and comedic way,” a 19-year-old male wrote. “I feel hopeful.”

PTSD Play Finds Laughter in Healing

Comments