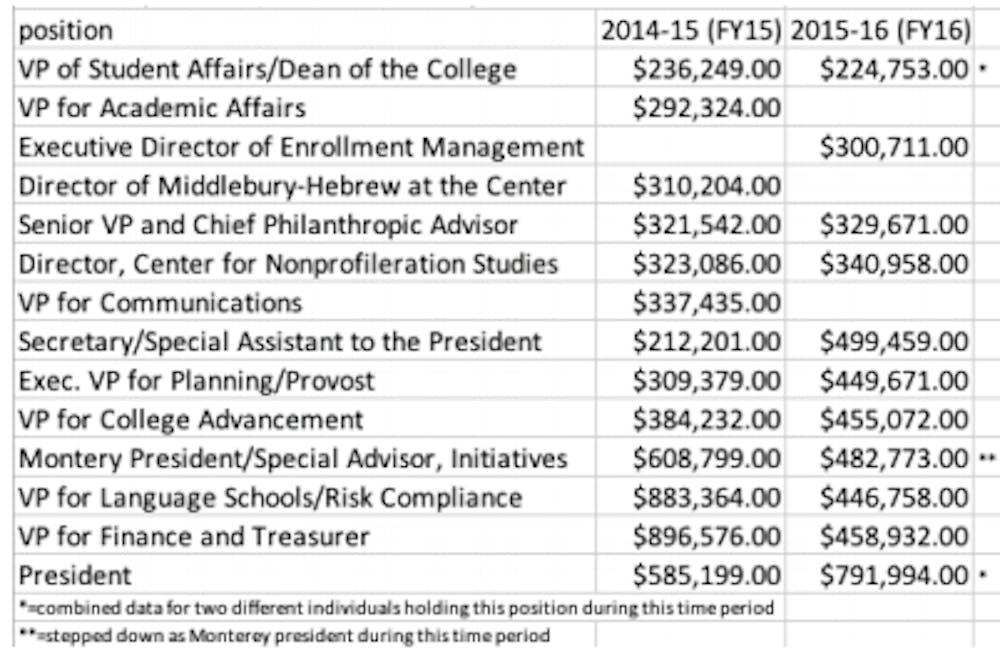

In case you don’t know me, I’m that guy at our financial meetings — the one who’s always asking questions (but not necessarily getting answers) about Middlebury’s executive pay. The data I’m talking about, the total compensation of our top administrators as listed in Middlebury’s IRS-mandated Form 990 filings for 2014–15 and 2015–16 (the most recent available), are shown in the accompanying chart.

I suspect that many students, faculty and staff will find the sheer magnitude of these numbers infuriating, especially at a time when tuition increases are significantly exceeding and average faculty and staff salary increases are lagging behind the rate of inflation. But I would argue that it is even more important to scrutinize executive compensation for the same reason we need to pay top executives well in the first place: because incentives matter.

According to the administration, a major contribution to these total compensation numbers has been a program of “stay bonuses.” Nominally associated with the presidential transition in 2015, these payments have been justified by the administration as a necessary tool to prevent senior executives from leaving for other institutions. According to our available Form 990 filings, top administrators accrued these bonuses regularly over several years (at least six in some cases). However, because these bonuses are paid out as lump sums, we account for them as one-time expenses, meaning that they are taken directly from the endowment rather than falling within the constraints of the operating budget. In other words, they are funded by dipping into our long-term savings — an approach that is often suggested, and rightly rejected, to address budget gaps in other areas.

While the administration has pointed out that our compensation committee sets executive pay to be competitive with peer institutions, it has also acknowledged that this comparison does not take these bonuses into account. And although this bonus program originated before she arrived, President Patton reported to Faculty Council in February 2017 that she has continued it and added additional bonuses for current administrators. At that meeting she also reported that former President Liebowitz is due a bonus that has not yet been disclosed in the available filings.

Since the right incentives can easily pay for themselves through the institution’s overall success, evaluating this approach requires us to reflect on Middlebury’s financial performance over the corresponding time period. Despite a strong economy, we swung to eight-figure deficits that peaked in 2015–16 at more than $22 million, roughly triple our worst shortfall during the 2007 financial crisis. Our credit outlook was downgraded, our auditors found “material weaknesses” in our financial statements, and we recognized that our accounting had underestimated depreciation costs for our facilities compared to generally accepted accounting principles. We added a new $46 million field house featuring a $7.8 million squash facility, a new office in Washington, D.C., and new off-site summer programs at the same time as we did little to address the college’s academic space needs, so that we are now scrambling to build a temporary building to accommodate growth in science enrollments and create swing space for overdue renovations. A New York Times report on family income of domestic college students listed us as the #9 college in the country for the highest ratio of the top one percent compared to the bottom 60 percent.

These outcomes have followed alongside growth in spending. We entered into an agreement to lease a spacious new townhouse dormitory, trading upfront building costs for ongoing rent payments. We committed to pay $14 million over 20 years to the town for a new municipal building and recreation facility, enabling us to establish a park entrance to campus on the site of the former town hall. We added new layers to the administration and created many new administrative positions. We brought in gifts and grants through new initiatives, centers and facilities, but now face the costs of continuing programs past the “fiscal cliffs” when their initial funding expires, along with the ongoing expenses associated with administration and maintenance. The Monterey merger and other ventures that were justified on the grounds that they would generate positive net income, or at least break even, have instead required millions of dollars in subsidies to cover their deficits, indirect costs, opportunity costs and assumed debt.

While faculty do not have access to the detailed financial numbers behind these trends, one data point from our Form 990 filing is that we spent $69.7 million on management and fundraising in 2015–16, compared to the $89.1 million we spent on instruction. It is taking nothing away from the dedicated individuals working hard at the jobs they were hired to do to question whether this allocation of resources reflects the core values and goals of a nonprofit educational institution.

One can argue that the value of these efforts justifies their costs, and that hindsight is 20/20; we should be willing to take risks, not all of which will succeed. But the structure of our executive compensation casts significant doubt on those arguments: Highly compensated administrators with one foot out the door might naturally be expected to focus more on short-term, externally visible benefits and correspondingly less on long-term costs and planning.

In this light, it is also natural to ask how these incentives interact with our decision-making, either explicitly or implicitly. To what extent did the opportunity for administrators to increase the scope of their responsibilities, and therefore their compensation, enter into their decisions to merge with the Monterey Institute, to embark on our now-terminated Middlebury Interactive Languages joint venture, or to expand administrative programs and staff? As we used to say when I worked in the software industry, maybe it’s not a bug, it’s a feature.

It is particularly dangerous, as became clear after the dot-com bubble, to judge executives by the revenue they bring in without paying corresponding attention to the associated costs. But that is essentially what happens if the administration is evaluated by its ability to hit fundraising targets. Doing so creates a powerful incentive to solicit donor support in the areas that will yield the largest gifts, rather than focusing on the most lasting and cost-effective contributions to our highest educational priorities.

None of this is to suggest that anyone actively plotted to undermine the institution’s long-term well-being. As biology teaches us, systems will evolve in response to selection pressure alone, without the need for an overarching design; if one set of practices leads to growth and rewards, it will become dominant. Unlike the natural world, however, in our ecosystem these incentives are within our control because they are created within the institution itself.

Success in higher education is, fundamentally, a long-term proposition. While it’s easier to quantify quarterly fundraising revenue, it takes time to separate true progress from window dressing. As a result, our compensation practices should establish incentives that reflect long-term educational outcomes. They should be applied proportionally across the institution rather than to a select few, and should reward effective deployment of resources over mere expansion. Creating such a system is easier said than done, but facing up to and learning from our past experience is a good place to start.

Noah Graham is a professor of physics.