Trigger Warning: Many artists who have been accused of sexual assault and sexual impropriety will be referenced in this review. For campus resources surrounding sexual assault, visit go.middlebury.edu/sexualviolenceinfo. Also, visit MiddSafe’s site at go.middlebury.edu/middsafe or student group It Happens Here at go.middlebury.edu/ihh.

To report a sexual assault, contact Middlebury College’s Title IX Coordinator Sue Ritter (sritter@middlebury.edu) at 802-443-3289. Her office is in Student Services Building 213.

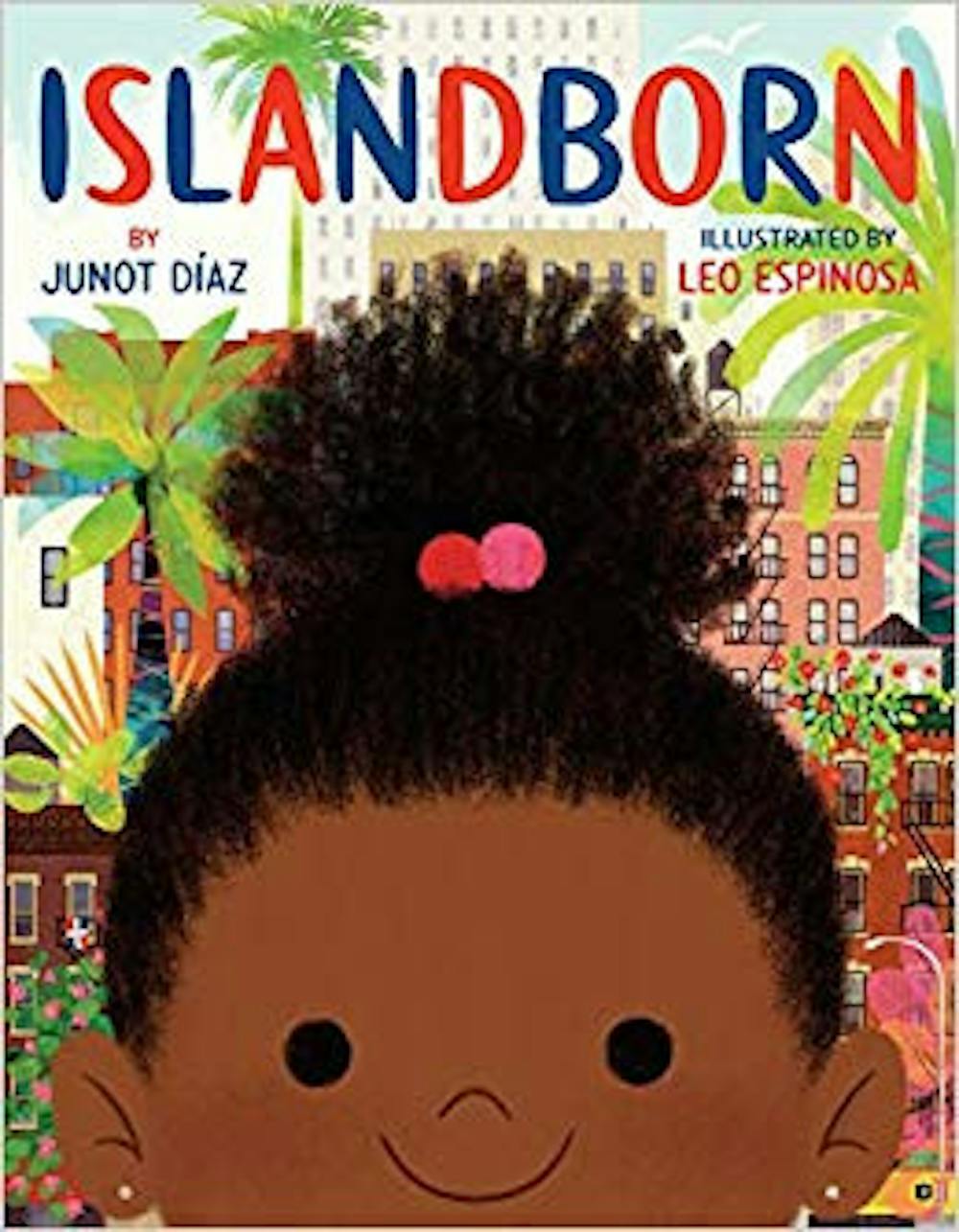

This children’s (?) book is an absolute love letter to the Dominican Republic, all of the brown people born there and those who populate its diaspora. Pulitzer Prize-winning author Junot Díaz scribes a brief and endearing tale around Lola, an elementary school student who was born on the Caribbean isle but can’t seem to recall any of its details. Lola’s teacher gives her ethnically and racially diverse class an assignment of drawing a picture about where they are from and Lola must tap into her community, asking neighbors and relatives about their memories, in order to create a picture of an island that lives within her.

Díaz’s narrative has much in common with his own: he was born in the Dominican Republic and came to the United States as a child. His identity then, like Lola’s, is transnational — rich because it is informed by two places, yet negotiated, too, as it is a hybrid. On the journey, readers tour a neighborhood that is filled with people who trace links to the Dominican Republic and cultural products that come from the island, like empanadas. The omnipresent music, too, is a cultural motif. What Lola and readers realize is that many Dominicans are in diasporic spaces because they were escaping a reality that was less favorable. Without ever explicitly mentioning the Dominican Republic’s former dictator, Rafael Trujillo, and the many deaths that resulted from his power, Díaz is able to conjure a time when living on the island was equivalent to living under an ominous and encompassing threat.

The book is impressive in that it features a brown girl with highly textured hair leading an adventure of historical memory. There aren’t many I can readily name that do this. A better choice could have been made in terms of the size and style of the font used within the work. The text is fine and narrow and sometimes exceeds 100 words per page, which suggests this work is not intended for young children. In that respect, I think Díaz struggled to truly identify his audience. If the readership is, say, aged 5-10, like the main character, “Islandborn” comes off as text-heavy and the political overtones that reference a dictatorship may be lost on children without a good deal of contextualization. That is, without a parent or adult nearby to provide explicit explanations of an era of pain and oppression, children attempting to read this work independently are likely to miss an important layer of the narrative.

I suspect it would be remiss to review one of Díaz’s works without acknowledging the accusations against him in the wake of the #MeToo movement. To some people it is not reaching to say that over the last 15 years, particularly following the publication of “The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao,” Díaz had been elevated to the status of a literary god.

Díaz became known as a go-to author who would champion the voices of the marginalized and oppressed and has received non-stop invitations to speak on all sorts of topics including the politics surrounding writers of color and transnational writers in the United States. I, too, sought out his thoughts and takes on contemporary politics, following his Facebook publications with attention, admiration and gravitas. I was also impressed by his professorship at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and his participation in workshops designed to further develop the work of new writers of color. In short, my admiration ran so deeply, I wanted to marry this man.

Then some deeply concerning reports were made about his character and his behavior regarding how he has treated women and how his power allowed him to treat women abusively without repercussion. As my inclination is to believe people when they identify perpetrators of abuse, misconduct and misogyny, the stability of the pedestal upon which I and we, collectively as a culture, had placed him, was shaken. My trust as an avid and faithful fan was compromised.

If he behaved poorly in the dark — which I believe he did — then what was “Islandborn” when placed in the light? Did he really believe in the power of a story featuring a young Caribbean girl of color? Or was it just a convenient marketing ploy that further branded him in a favorable light? Or something in between? Did he realize that young girls of color mature and become women of color? And that those women of color were being disrespected and violated by his allegedly abusive behavior? Are humans identifying as female only worthy of respect and protection before they develop secondary sexual characteristics that can make them desirable to men? Are they afterwards “prey” and “fair game”?

Perhaps needless to say, I can’t read his work with the same eyes I would have in 2017. Díaz’s works have their merit, sure. But divorcing the writer from the work he/she/they produce(s) is, in a word, challenging.

Another writer whose character has come under similar scrutiny following accusations of sexual harassment is Sherman Alexie, author of “The Absolutely True Diary of A Part-Time Indian.” Bill Cosby, too, star of “The Cosby Show,” is serving time for three counts of aggravated indecent assault against Andrea Constand. Comedian Louis C.K. from “Louie” publicly confessed to exposing his genitals to his female colleagues, another form of sexual misconduct. Aziz Ansari, creator of “Master of None,” has been accused of misconduct. And Dr. Avital Ronell of New York University, author of many works in our collection, including “Crack Wars” and “Stupidity,” has been accused of sexual harassment, sexual assault, stalking and retaliation.

I live in a conflicted space because I love(d) what some of these artists produced and, simultaneously, I hate their misogyny and abuse.

If you want to read another work that treats a transnational narrative stemming from the Caribbean, see Edwidge Danticat’s “Breath, Eyes, Memory,” which, admittedly, is triggering in a host of different ways but features Haitian characters and engages a transnational discourse.

Literatures & Cultures Librarian Katrina Spencer is liaison to the Anderson Freeman Center, the Arabic Department, the Comparative Literature Program, the Gender, Sexuality & Feminist Studies (GSFS) Program, the Language Schools, the Linguistics Program and the Department of Spanish and Portuguese.

The Librarian Is In: “Islandborn”by Junot Díaz, illustrated by Leo Espinosa, 2018

DIAL BOOKS FOR YOUNG READERS

Comments