After a two-week period in which an offensive chemistry exam question came to light and a problematic cartoon was shown in a geology class, increased attention has been focused from students, parents and faculty on the sciences — specifically on the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry — to address how classes in those departments could be more inclusive.

Many students said that in the midst of this renewed focus, they did not want the discussion to start and stop with specific incidents. Rather, students hope the conversation will shift toward the deeper-seeded issues within both the chemistry department and the STEM program that make certain students feel unwelcome, especially women and students of color.

The Curriculum: An Ethos of Erasure

Many students said that the way knowledge is framed in science classes does not do enough to address the harmful history that often accompanies scientific research, which can leave women and students of color feeling ignored or unseen in the classroom. While several students framed their experience in the context of the Chemistry Department in light of recent events, they also spoke about a wider culture that spans multiple academic departments.

“There is an overwhelming sense in STEM classes that what we do is scientific and logical and based in reason, and so it has nothing to do with diversity, inclusivity and what people view as more social issues,” said Vee Duong ’19, a comparative literature major who also completed the pre-med track. “There’s very little sense that we as students and professors in STEM have some sort of stake in creating more inclusive environments. And there’s very little conversation about what that inclusive environment might look like.”

Duong said that some professors highlight women and people of color who have contributed to scientific advancement, but not every professor takes the time to acknowledge the work of those who are often overlooked. She also pointed out that in her experience this problem is not unique to science classes but rather occurs in all academic programs.

According to Duong, the decontextualized environment in the sciences puts pressure on students of color to achieve at high levels and defy stereotypes.

“There’s this sense that in the classroom I need to prove myself and perform well and be different,” she said. “When you feel like you need to meet objective standards that are really not objective because they have been created to marginalize certain communities it becomes a really tough mental personal battle to assert yourself and build a space for yourself in that classroom.”

Another student, who asked to be referred to as Kayla, said that this struggle to assert yourself can cause students to drop out of the sciences, which perpetuates a larger issue of underrepresentation. Kayla spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of retribution from faculty.

“There’s already a lot of widely documented evidence and studies showing that students of color from low income backgrounds who come from underfunded public high schools have higher rates of getting out of STEM, even if they come in studying STEM,” she said.

Rachel Hemond ’19.5, a molecular biology and biochemistry major, pointed out that these concerns relate to the student-led movement to decolonize the curriculum, which has gained momentum this spring. That initiative asks professors to change which perspectives are actively taught in their classes.

“We never talk about where our knowledge comes from in STEM, and in other disciplines, that is so unacceptable pedagogically and epistemologically,” she said, adding that she believes many professors have this knowledge but may be unsure of how to integrate it effectively in their curriculum.

“There’s this idea you can separate the subjectivity of history from the objectivity of scientific knowledge and that’s not the case. Everything is situated,” Hemond said. “It doesn’t surprise me that BiHall has issues with prevalent and systemic sexism and racism and classism because the very disciplines of science that they are professing to teach us are filled with those things and fundamentally built on them.”

Kayla agreed that in STEM classes professors do not always incorporate discussion that puts knowledge in context.

“There’s a history in science of people from more privileged backgrounds claiming and taking credit for other people’s work,” Kayla said. “And we never talk about that in class because we’re always focused on the hard science and getting through what you need to to get into medical school and PhD programs and the next thing you’re going to do in lab.”

Bob Cluss, the chair of the Chemistry and Biochemistry Department, said that the 12-week semesters make it hard to incorporate social issues into the curriculum to the extent that some professors would like to.

“If we had a 14-week semester and we were still covering the same topics, we would be able to integrate social issues better, we would be able to use contemplative practices, we would be able to do a lot things we’re not doing now,” Cluss said.

Cluss, who has been chair of the department for two years, said he believes it is deeply important to make space for discussions that contextualize scientific knowledge, but that it has to be done correctly, which requires both time and proper training for professors.

“If we’re talking about something that is difficult then we all need to have the time to look at all the nuances that connect to it,” he said. “But I think that’s what we should do. Science is a part of society and we really should be connecting these things, not pulling them apart.”

Problems With Professors

Many students also reported that one professor — Steve Oster, who teaches the organic chemistry lab sessions — creates an environment that favors some students over others and often makes women and students of color feel uncomfortable. Oster is the only lab professor for those courses, which are required or recommended for many STEM majors and the pre-med track.

“He’s someone who shamelessly makes it obvious to the class who his favorites are, which is usually a very predictable demographic, and he always directs his attention to validate them in the classroom,” Kayla said. “This can imply that some students’ educations are valued over others in a classroom and that can get internalized by students who are being ignored, making them think that they don’t matter and that they don’t belong in STEM.”

Kayla, who identifies as a student of color, said that Oster’s behavior often goes beyond favoritism.

“It is very intimidating being in a classroom where the professor is a white male joking about things that are often racist or sexist and expecting you to laugh along, and if you don’t laugh along he just walks past you and doesn’t bother to have a conversation with you,” she said. “I have particularly had experiences where he has called me by another brown girl’s name and doesn’t bother to get to know who I am but does get to know everyone around me who is not a person of color.”

Duong had a similar experience of feeling marginalized in Oster’s class.

“He never engaged with the students of color in the same way that he engaged with white students,” she said. “When he was going around to introduce himself to everyone in the class, he would go to everyone’s laboratory hood but he completely skipped over mine. I could tell, I could see him looking at my name, and he didn’t know how to go about saying my name, I guess, so he just skipped over mine and went on to the next person.”

For many students, especially women, Oster’s reputation preceded him because older female students warned them about his behavior before they took his class. This was the case for Charlotte Cahillane ’19.5, who said that she went into Oster’s class on alert because of what she had been told. Still, Cahillane said she believed she would have been uncomfortable in Oster’s class regardless of any preconceived notions she brought with her.

“I’ve heard he might not have this anymore, but he used to just carry around this golf club and just stand behind students with it over his shoulders, waving it around, sort of wielding it in a way that made you feel moderately threatened at the same time that you felt confused. Why would you have a golf club in a chemistry lab? There’s so many breakable objects, people break objects without golf clubs, you don’t need a golf club in there,” she said. “In general, he doesn’t make me feel comfortable as a professor. I wouldn’t want to be alone with him in a room talking about chemistry. Especially with the door closed. Not because I think he’s going to do something, but because I know I would not feel 100 percent in control.”

Other students cited their frustration that Oster’s bias also seemed to extend into his grading as well.

“You could take two lab reports that basically have the same things written on them, almost always the guy will get a higher score than the girl,” Maggie Phillips ’19 said. “It feels like he’s always standing over the women to make sure they know what they’re doing but lets the guys do their own thing.”

Phillips said she worries about the impact that Oster’s attitude toward women has on her fellow students.

“I think that a lot of people know that he’s outrageous and don’t take him seriously, but when you’re watching women and students of color be treated differently, you’re subconsciously going to think that they’re dumber or more inept,” she said. “I’ve noticed in my upper level classes that I’ve been talked down to by my male classmates and I wonder how much of that has been learned by seeing faculty members treat women and people of color differently. And I would almost argue that’s more damaging.”

Cluss said that he cannot speak to specific personnel issues, and he pointed out that different students have different experiences in the same classes. He also reiterated the department’s commitment to making their classes welcoming spaces for all students.

“There are a range of student opinions about faculty. That said, we want all students to feel that they’re welcome in a class and that they’re treated fairly. That’s really critical. We’re more committed to that than ever,” he said. “If there are students that feel that certain students were favored or certain students were marginalized, that’s never a good thing. And that needs to be attended to.”

Oster did not respond to the The Campus’ request for comment.

All of the students interviewed for this article who mentioned they had issues with Oster said that they left comments in their course response forms at the end of the semester that reflected their negative experiences with Oster, but that nothing seemed to change.

Course response forms can be viewed by the professor who taught the course, the chair of the department, and the dean of faculty, as well as by the the Promotions and Re-appointments Committees for any faculty member under review.

“Course response forms are intended to provide students with an opportunity to give feedback — positive and negative — on their experience in a course,” Dean of Faculty Andi Lloyd told The Campus, adding that the forms did not originate as a way for students to report serious concerns or problematic behavior, nor are they used that way now.

“That’s not to say that there would not be follow up on something reported in a course response form, but, depending on the situation, there might be better or more effective ways for someone to raise a concern,” she said.

Lloyd recommended department chairs, program directors, advisors, Commons faculty heads and Commons deans as good options for students to report a specific concern. However, many students said they did not have a clear idea of who they should approach with these concerns while they were in Oster’s class.

Several also mentioned their complaints to other professors, but were unsure what other options were open to them.

“I talked to faculty members about him but I didn’t know I could do more than that other than complain about him on my course response forms and talk to my advisor,” Phillips said. “When I would bring it up to faculty they would say I know, this is a problem, we’re addressing it. But then nothing would really happen.”

Kayla echoed this, saying that the faculty she spoke with also seemed aware of the issue.

“All of them said that this was a known problem in this department and that they also did not like the way this professor carried himself around, but it didn’t seem like there was any foreseeable way to have him do something to change,” she said.

Despite the negative experiences that students have with aspects of the STEM program, they cautioned against the assumption that STEM classes are the only academic spaces on campus with a bias problem.

“I actually don’t think that BiHall is the worst on this campus by any means. I think that it gets a lot of publicity because people expect to see it there and I think that’s also problematic,” Hemond said. “I think that BiHall is a microcosm of this campus as a whole.”

Kayla agreed.

“There’s always micro-aggressions everywhere,” she said. “That’s not unique to STEM, that happens everywhere.”

Upcoming Changes, Ongoing Conversations

In light of recent events, Cluss said his department has been engaged in a lot of conversations about how to respond to recent issues.

“There’s a lot that’s been happening in a very short period of time at a very busy time of the year,” he said. “I feel like we’re doing everything we can right now, and we need to. This is a very important issue.”

The week after the all-school email about the offensive chemistry test question, the faculty held a meeting to gather feedback from their majors. Phillips, who is a Chemistry and Dance double major, was one of the students at that meeting, and decided to organize a sensitivity training for chemistry professors through her connections in the dance department.

“I went to talk to dance professors Lida Winfield and Crystal Brown to ask if they could potentially do a training with all the science faculty and students who would be interested and they said yes, and that they had actually been doing a bias training with all of the Addison County elementary school students and we could do the same thing for the science faculty,” she said. “I think a lot of faculty are open and wanting to make a difference but they just don’t know how. And I think a lot of faculty are busy and it doesn’t seem important.”

The training was set to occur on Wednesday, May 1, after the print deadline for this article.

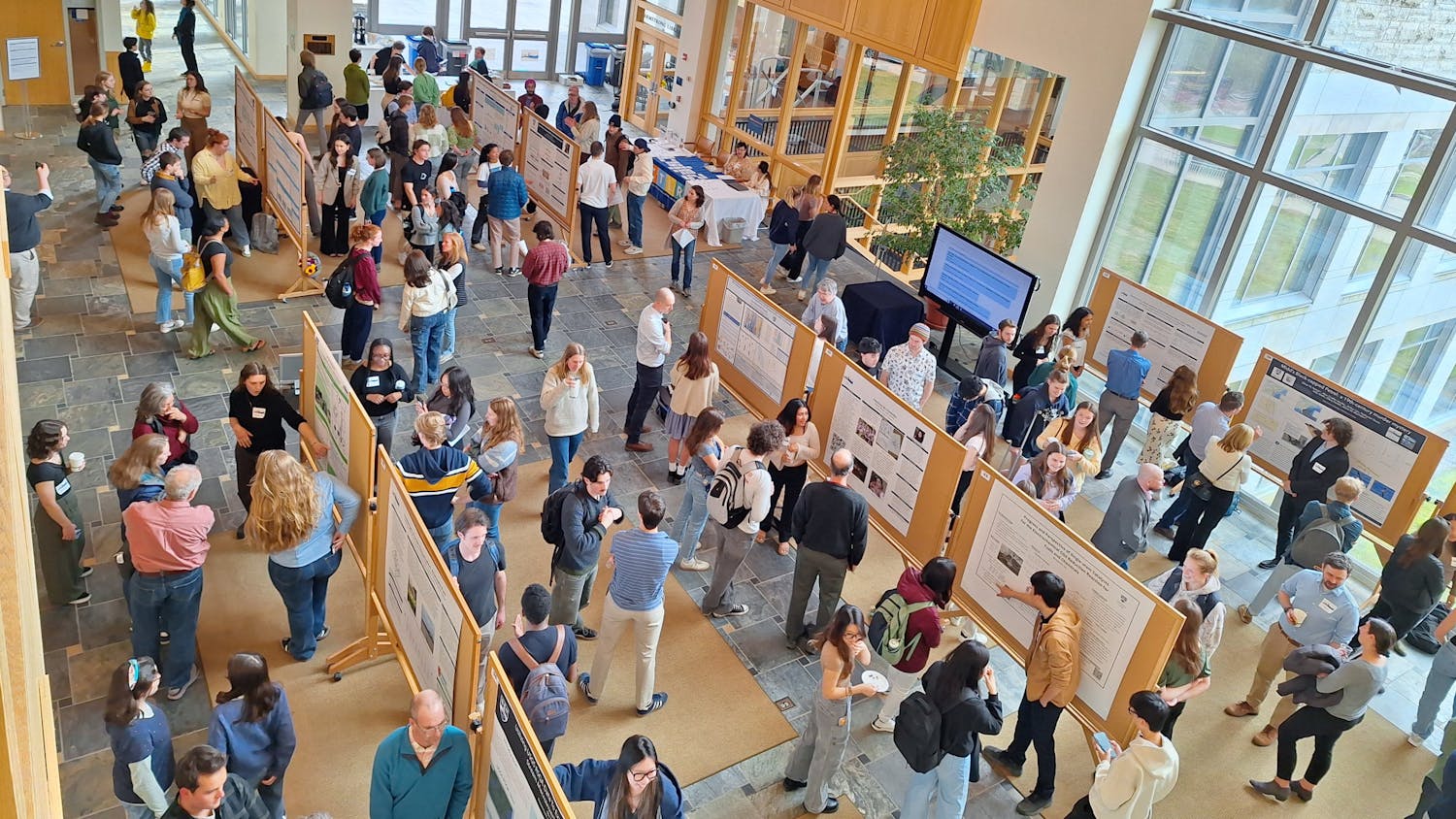

The STEM Pedagogy Group, a group of about 60 STEM faculty and staff who want to implement better and more inclusive teaching practices, also recently sent out a survey, which they had been working on for about a year and which they hope will help them get feedback from students.

Associate Laboratory Professor in Biology Susan DeSimone, a founder of the STEM Pedagogy Group, said that the goal of the survey is to collect accurate data about how students in STEM feel about their classes.

“Our conversation over the semester last spring made us realize that one of the things we really needed was to understand how our students perceive our environments,” she said.

DeSimone said the survey was sent to the roughly 1,800 students who took a STEM class during this academic year on April 24.

“The goal is to collect data to address the question and not presume that we know what is or isn’t happening in our students’ experiences,” she said. “One of the things the group really wants to do is to create more inclusive pedagogies and more inclusive spaces, and so this survey could be used for us to develop practices to potentially look for grant funding to do that.”

Cluss said these new discussion come in a long line of cultural shifts he has observed in the community since he has been here.

“This is a very different place than it was even five years ago,” he said. “I think our community throughout is more diverse. I think everyone’s voice really needs to be heard and in some instances it almost takes a critical mass of people for that to happen and I think we’re there in our community. And that’s good, that’s important.”

“We have a heightened awareness of this now,” he said. “Sometimes you need to shine a very bright light on things but we’re learning from it. This has been really, really hard for our community, but these are the times where we learn and grow, too.”

Comments