After wrapping up the college's year-long workforce planning initiative this May, a process that saw 37 staff members take voluntary buyouts and caused a redistribution of workload among remaining staff, administrators announced via email to all college employees that the process had been a success — Middlebury could reduce its deficit without resorting to layoffs.

But an external email sent to facilities staff on Aug. 8 suggests the starkly different story, that some workers didn’t think workforce planning had been so “voluntary” after all.

“Middlebury Needs a UNION! -read on your break” the subject line of the email said.

It spelled out some of the pitfalls of the workforce planning process: Staff felt voiceless, overworked with insufficient pay, and as though the ground had been pulled from beneath them when they were offered buyouts and switched into new roles. Facilities staff specifically — those who work in maintenance and operations jobs, like custodial and groundskeeping services, as well as jobs in planning, design and construction — have reported to The Campus feeling exhausted and frustrated by failures in communication, too-long hours and last minute call-ins.

“I don’t know a bunch about unions — still don’t,” one facilities staff member said. “But I know the way that people get treated here. I’ve seen it. I just feel like we’ve got to do something.”

Throughout the summer, the email’s sender, David Van Deusen of the Rutland-based branch of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME), met with facilities staff who sought to discuss how organizing a union would mitigate the heightened voicelessness brought on by the workforce planning process.

Not enough facilities staff have signed union authorization cards to trigger a vote to organize. Many said they see this as a sign that union efforts have failed. But Van Deusen remains adamant that efforts are ongoing. And facilities staff are insistent that something has to give.

Most of the 12 facilities workers The Campus spoke with for the story spoke on the condition of anonymity, for fear of retribution from peers and upper management.

Workforce planning raises “unanswered questions”

Most Middlebury students don’t know what workforce planning really means. But for staff, the process — which the college announced in June 2018 as a way to cut personnel costs and distribute work more efficiently — was ever-present for the better part of a year.

Department managers were tasked last fall with leading discussions within their divisions about how they could reorganize work more efficiently and cost-effectively, with the aim of shrinking staff compensation costs by 10% amidst an exigent budget deficit. That winter, senior leadership, in collaboration with human resources, finalized a list of positions that they would cut based on those findings.

The college identified 150 staff positions to be eliminated, though 100 of that number were “were already vacant through attrition and restrictions on re-hiring over the last few years,” The Campus reported in May. In February of 2019, the college handed out applications for buyouts — formally called Incentivized Separation Plans (ISP) — to 79 staff members, in hopes of cutting 45 of the remaining positions. Twenty-eight of those applications were offered to facilities and dining staff specifically.

The college sent more applications for the buyouts than were necessary, in the hopes that enough staff would elect to take them and the college would not have to resort to involuntary layoffs. If more staff than necessary applied, the most senior staff were offered buyouts first.

The college also created “close to 40” new staff positions based on needs identified during work reevaluations, according to Vice President of Human Resources Karen Miller. Applications for those positions were first made available to the staff who were offered buyouts, giving them the option to apply to stay at the college, rather than taking ISPs. To protect the privacy of the individuals who opted to take buyouts, the college has not made public the list of eliminated and added positions.

Ultimately, 37 staff took the buyouts, nine of whom were employees within facilities and dining. The college had hoped more staff would apply, but the number proved sufficient — the college did not have to resort to layoffs.

“This process has been both lengthy and challenging, and caused many in our community significant uncertainty and discomfort,” said President Laurie Patton in a May email to staff. “Thanks to your participation, the process was successful.”

Last year, The Campus reported growing anxieties among staff as they waited to hear from the administration about the futures of their jobs. For staff in some departments — like dining, in which a natural reduction of positions left few to be forcibly cut — these uncertainties have since mostly subsided. But in facilities, anxieties have subsisted. In some cases, they have worsened.

“There were a lot of unanswered questions. There still are a lot of unanswered questions,” said one Middlebury facilities staff member, a supporter of the union.

A 2017 survey, administered by the consulting firm ModernThink, shows that staff discontent surged even before workforce planning began. That survey showed frustration with communication from the Senior Leadership Group — Patton’s 17-member advisory council — a lack of transparency with decision-making and dissatisfaction with compensation, among other areas.

Still, workforce planning seems to have exacerbated many staff concerns. Some, for example, are frustrated with how work has been redistributed since some positions were cut, which has caused employees to feel overworked and underpaid.

“The work amped up with fewer people to do it,” said the aforementioned facilities staff member. “A lot of the extra stuff is taking away from the stuff that we need to do daily.”

The worker said he was frustrated with what he felt was a murky process. Decisions about the “voluntary” process were often made behind closed doors, he said, and the redistribution of work showed a lack of understanding about the work being done. “There was nothing voluntary about it,” he said.

Norm Cushman, vice president for operations, said communication can be a challenge in a department with so many workers. “It would have been very difficult to have solicited everyone’s input,” he said.

Cushman said the process of work redistribution will play out piecemeal, as employees who took buyouts gradually leave the college and their departments develop strategies for how to “do less with less.”

Low pay forces employees who work two jobs into a “balancing act”

The Campus has previously reported low wages as a source of dissatisfaction among employees. Separately, pro-union staff who spoke to The Campus said low wages were a major reason they sought to organize.

Many employees have to hold multiple jobs to survive. That balancing act, another facilities employee said, can become incredibly burdensome when workloads at the college are also increased in light of workforce planning. When many facilities staff did not show up to work after an unexpectedly severe snowstorm last year, for example, administrators questioned staff priorities.

“We had a meeting with a manager who was extremely unhappy because a lot of people weren’t here helping,” the employee said. “He told us that if we had second jobs, we needed to not go in and instead had to come in and shovel.”

The college has consistently framed workforce planning as a way to make staff feel more invested in the future of the institution. But according to staff, it doesn’t always feel like that.

“Yeah, you could say workforce planning is for us, because now [the college is] financially sustainable,” said Staff Council President Tim Parsons. “But if you’re only making $12.07 an hour and your shift in the custodial wing starts at 4 a.m., workforce planning doesn’t really feel like it’s for you.”

These low wages have led to shortages in some areas, like custodial and recycling services. To address these shortages, the college is currently spearheading a compensation review with an external consulting group. The aim of the study is to gather “market data” — information that will indicate what the college needs to pay going forward to make itself a competitive employer.

David Provost, executive vice president for finance and administration, said the college is undertaking the review now because it has been nearly a decade since the last one of its kind. He also said that the college has seen increased turnover in the last two years in positions within the lowest two pay bands, in which many facilities positions fall. Wages for OP1 positions — for example, some dining hall servery positions — begin at $11 an hour, while OP2 positions — including some groundsworking and custodial jobs — begin at $12.07 an hour.

“Benefits here are a lot better than what you would find anywhere else around here,” said one facillities employee. “But I can’t go down to Hannaford and buy groceries with my benefits.”

Meanwhile, staff spoke about how comparable positions in town had wages that started three or four dollars higher, although without comparable benefits. Separately, custodians told The Campus that hiring shortages in custodial services might be due to the high costs of living in Addison County, costs which workers on an OP2-level budget are often not able to shoulder.

“We know over the last 18 to 24 months it has been more difficult to attract and retain OP1 and OP2 level positions,” Provost said. “If the review suggests we need to increase these salaries, then we will.” He added that the decision would have to be contingent on timing and availability of financial resources.

The college had to tackle workforce planning before the compensation review, Provost said, because addressing its financial management had to be a fiscal priority, given the severity of the deficit.

Provost said he is expecting the study’s data to show that the college should pay its OP1- and OP2-level employees higher wages. The study is set to be done by the spring. At that time, the administration will begin to work its findings into the budget for the 2021 fiscal year.

“A slap in the face”

The college did not officially lay off any employees. Some felt the offers they received backed them into corners anyway.

One employee, a servery worker who has been at the college for 31 years, said her situation felt like “a slap in the face.” She was previously employed in a facilities office job before her position was cut.

[pullquote speaker="" photo="" align="center" background="on" border="all" shadow="on"]At the college, seniority has never meant anything. I’ve been here 31 years — I’m a loyal worker, have always been on time, never been sick. Didn’t matter at all.[/pullquote]

Even though she shared a similar workload with the two other employees in her previous office, she had a different job title from her co-workers and hers was the only position that was cut. In other offices, where multiple workers held the same positions, the process was more “voluntary,” since one worker’s choice to take a buyout or job transfer meant others could refuse.

The servery worker was, as multiple staff members put it, “workforce planned.”

“At the college, seniority has never meant anything,” the employee said. “I’ve been here 31 years — I’m a loyal worker, have always been on time, never been sick. Didn’t matter at all.”

The staff member was informed by supervisors that her position would be cut toward the end of that phase in the process. But she couldn’t afford to take the buyout package the college was offering. The staff member instead applied for several of the then-newly-created positions posted on a private portal. Many of the available job postings required degrees, she said. “I don’t have a college degree,” she said. “Doesn’t mean I didn’t have the qualifications — I didn’t have the degree.”

All jobs for which she was eligible required higher levels of physical activity than she was used to. After working at a desk for so many years, the transition to a job that requires her to carry heavy loads and stand for hours at a time has taken a toll. Last week, she suffered a workplace injury.

Contacted by AFSCME while she was still in a facilities position, the staff member attended initial meetings and supported the effort to unionize. She said she would support unionization among facilities staff, even in her new role, “Because you’d have someone else looking out for you besides the people who are higher up here,” she said. “They expect the lowest paid people here to work the hardest.”

Despite low wages, staff like the servery worker identified the benefits the college offers to its faculty and staff as exceptional in comparison with other positions in the area. Among them are good healthcare, extensive retirement plans and paid time off, as well as discounts at some stores, free gym passes and roadside assistance.

“If it was not for the benefits, 90% of these facilities people would not be here,” the first facilities employee said.

“Benefits here are a lot better than what you would find anywhere else around here,” said the other. “But I can’t go down to Hannaford and buy groceries with my benefits.”

“Middlebury Needs a UNION!”

Van Deusen, the union rep and the president of the Vermont American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO), said he was contacted by facilities employees over the summer about starting a union.

While some staff concerns, like low pay and abrupt, last-minute shift scheduling, have been prevalent for a long time, Van Deusen believes this round of workforce planning catalyzed the staff’s outreach.

After their first meetings in Ilsley Public Library in July, Van Deusen said he was in contact with “dozens of facilities staff.” At subsequent off-campus gatherings, he spoke with interested parties about what the union could offer them. Many were intrigued.

One of the facilities workers told The Campus he “absolutely” supports the formation of a union, “Mainly for pay. And also, to have a voice.” He cited the workforce planning process as a period during which he felt particularly left in the dark by his superiors.

The servery worker said she would be in favor of a facilities union, “because of the seniority part of it. And to negotiate a better raise,” she said.

Some workers were also inspired by the successful union effort at St. Michael’s College. In 2012, custodians there unionized with AFSCME. They later negotiated $15-per-hour pay in their second contract.

Despite this recent win for Vermont labor advocates, Sociology Professor Jamie McCallum, who specializes in labor studies, said union decline in the U.S. has been happening since the 1950s and picked up speed in the late 1970s.

Once word of mouth began to spread about the Middlebury union effort, Van Deusen handed out authorization cards for interested employees to sign. What followed was a flood of information and rumors circulating between staff and the administration. On Aug. 19, one month after union authorization cards were first distributed, Miller, the vice president of human resources, replied to the initial drive in a letter that administrators hand-delivered to all facilities employees.

“Middlebury supports your right to choose whether to unionize,” the letter said.

“We know that many of you have raised legitimate and important concerns about your jobs,” it later added. “We also believe that joining an outside labor union to address those concerns is not the answer.”

The letter highlighted some commonly cited “disadvantages” of forming a union, such as the potentially high cost of monthly dues.

A few days later, Van Deusen sent an email to facilities employees responding to the administration’s outreach.

“AFSCME, the labor union many of you are seeking to affiliate with, is aware that Management has been spreading false and misleading information in an effort to get you to NOT form a Union,” it said, before addressing what it called “actual FACTS” about forming a union.

In the days following, some staff opposed to the union left flyers in certain shops and break rooms on campus, countering Van Deusen’s points. Shortly after, the administration sent a list of FAQs to staff, based on questions it had received from facilities when administrators traveled shop-to-shop with Miller’s first letter.

The union effort has not yet reached the strong majority within facilities that it needs to move forward. There is no specific benchmark for that number, Van Deusen said, but it would have to be a number with which the group would feel comfortable. Some staff said they see the slowing momentum as a sign the effort is doomed. But Van Deusen said authorization cards have not been circulating for long enough to determine whether the effort will succeed or not. He plans to continue to collect and tally cards.

If he could gather enough, staff would then need to file paperwork with the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), an independent federal agency that protects the rights of private sector employees to better their working conditions and wages. The NLRB would then conduct a secret ballot election among facilities staff to decide whether a union would be formed.

If a majority opted for the formation of a union, the new effort would hold internal union elections for a bargaining team. From there, it would bargain a binding contract with the administration.

“This time next year, we would like to announce that a new union, with a contract, will be formed at Middlebury,” Van Deusen said. He hopes that contract would address staff concerns by forming a labor management committee, creating a binding grievance procedure and paying better for longevity and overtime, among other measures.

Not every staff member is in favor of a union coming to campus. One custodial worker said she would not support the formation of a union because she is worried about losing her benefits in the negotiations, although she is unhappy with her current wages. She was offered a buyout last winter, but did not have to take it because another worker on her team did.

“I enjoy my vacation time,” she said. “The health insurance isn’t what it used to be, but that’s changing in November, too. I enjoy my benefits.”

According to Miller, the college will put in place a new healthcare system this November, to go into effect in January, that will introduce more choice into the current plan.

Although some employees worry their benefits will be at risk if they unionize, McCallum said he finds it hard to believe that the college would target workers’ healthcare and benefits in negotiations.

Flyers outside a breakroom in the service building display messages from the college about employee benefits (top flyer) and a flyer detailing information about AFSCME dues (bottom flyer).

“If Middlebury were to threaten the good benefits that workers now receive if they decided to go union, it would be joining a long list of union-busting corporations,” he said.

Besides, he said that employees would have to agree on any union contract with the college.

“Workers vote on any contract a union signs, and they would only vote ‘yes’ on a contract when their benefits improved or stayed the same,” he said.

McCallum said he sees collective bargaining as an “essential ingredient of a democratic workplace.”

“We need a living wage here, where everyone can live and work with dignity, and that will mean paying workers what they deserve, not just what the market dictates,” he added.

Middlebury’s “Black Tuesday”: A union effort three decades ago

The servery employee, who has worked at the college for 31 years and supports a union, was freshly employed at Middlebury when a series of job cuts in May 1991 destroyed a long-held perception of the institution as a reliable place to work. She remembers the day those positions were terminated, which has since come to be known by some as “Black Tuesday,” as a day filled with tears and disbelief.

The college administration has taken measures to avoid an event like Black Tuesday from recurring. Patton told two Campus reporters in an article published by VTDigger this fall that memories of 1991 have influenced how the college currently handles staff reductions, emphasizing its focus on giving people more of a choice and inviting them to think about the long-term trajectory of the institution.

Miller emphasized a similar sentiment in her conversation with The Campus.

“I can say that we were intentional to make this as humane as we could, to make sure that this was not a surprise to people and that they were engaged in conversations,” she said about this year’s workforce planning. “We really worked hard to do that. Were we 100% successful? I hope so, but maybe not.”

As in 1991, this recent round of workforce planning eliminated specific job “titles” rather than “people,” and both years saw efforts to organize. In September of 1991, The Campus reported that staff across campus were “exploring ways to increase their input in administrative decisions.” This included attempts by some to form a union, organizing for which would last four years before ultimately breaking down in 1995 after failing to garner enough support.

Those attempts were aimed at creating a wall-to-wall bargaining unit — a unit that would include all staff, unlike this year’s single-department effort in facilities. Bill Jaeger, director of the Harvard Union of Clerical and Technical Workers (HUCTW), an AFSCME affiliate, helped spearhead that effort. His team was contacted by Middlebury employees in 1991, two years after HUCTW negotiated their own first contract.

Jaeger said attempts to unionize arose because of anger about the layoffs, but that at its core were more permanent longings for democratic change at the college.

“People were feeling like their eyes had been opened to how consequential and important it can be to have some breadth and some inclusion in important policy matters and in decision making,” he said.

HUCTW members visited staff in Middlebury to talk about the union, at times once per week. Most interest came from those in administrative and technical jobs, although there was some level of support and involvement in all staff departments, Jaeger remembered. In response, the administration called all-staff meetings to address the efforts.

That union was not able to pique sufficient interest, but Jaeger said staff who were involved were united around a shared sense of excitement for what they were building. “Most people are driven in the most steadfast way if they’re really building toward something that’s going to make a positive difference in the long term,” he said.

By 1995, when the effort fell, the college seemed to be undertaking corrective policies that gave employees some reason for hope.

College looks forward, staff still waiting for change

The college has reiterated time and time again that workforce planning is not a one-time process. This means that administrators are still assessing its successes, as well as where it’s fallen short.

Administrators are hopeful that the workforce planning process will allow the institution to run more efficiently and proactively in the future. Some of the new jobs, for example — including some of the positions offered to staff whose positions were cut, requiring college degrees — are more specialized, and were intended to take into account potential demographic shifts in Vermont so that the college can be an “employer of choice for the next generation,” Miller said.

“The whole purpose of the workforce planning is we’ve got to be prepared for our future,” she said. “I know it was a difficult process for many, but for some, I think it really helped us to transform and leap into that future state,” she added, citing the How Will We Live Together review as a concurrent, future-oriented process.

Miller said that the administration is committed to revisiting any “pain points” among staff and addressing them accordingly. At an Oct. 24 staff meeting, Patton announced that Special Assistant to the President Sue Ritter will do a listening tour throughout staff departments to hear employees’ concerns. The administration laid out its plan for the compensation review at that meeting, as well as several other measures, like a restatement that Senior Leadership Group would attend the holiday party this December, that suggest an effort to reinforce commitment to community-building.

The custodial worker and nearly every staff member interviewed for this article spoke about an intangible change that has made the working environment feel more corporate, and less warm and community-centered.

“When I first came here, it was different,” the custodial worker said. “It was more family-oriented, and everybody looked out for each other. It’s not like that anymore. It’s more sterile.”

Parsons, the staff council president, said Middlebury used to be a small institution with a real family feel. “As we have grown and expanded both our physical footprint here and our global footprint, we have somewhat lost touch with that,” he said.

“It would be a real challenge to bring that back,” he added.

Staff also overwhelmingly expressed large amounts of pride in Middlebury as an institution, a collective sentiment that is backed up by data in the 2017 ModernThink survey.

“It’s a great place,” the first facilities worker said. “And the benefits are great. We’re just underpaid for what we’re doing.”

This pride seems to leave many staff members feeling hopeful. But they’re also worried that the college will continue to disappoint them. Some left initial workforce planning meetings a year ago with the impression that “everything was going to be open and that communication was going to flow.”

“But it never did,” one staff member said.

“With workforce planning, there were so many unanswered questions,” he added. “The administration wouldn’t have been able to do that without talking to the union first.”

As the dust settles on the consequences of workforce planning, staff are still waiting to see tangible changes.

Citing low wages and ‘voicelessness,’ some facilities staff push for union

SADIE HOUSBERG

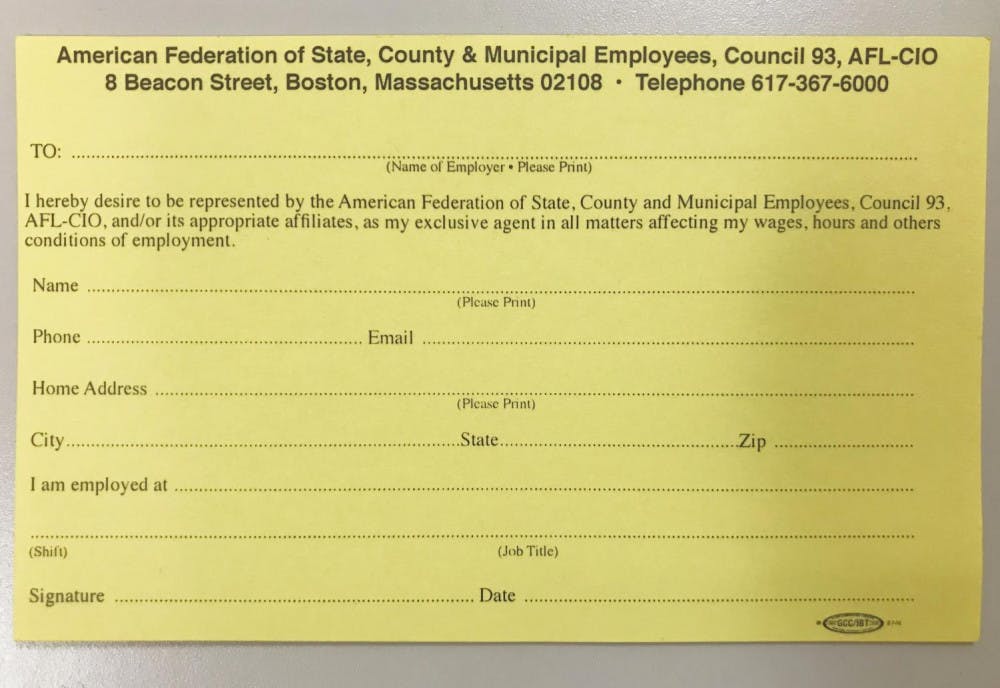

Authorization cards, like the one above, were distributed to some facilities staff starting this summer. At this juncture, not enough cards have been returned to the union representative to warrant moving forward with the effort.

Authorization cards, like the one above, were distributed to some facilities staff starting this summer. At this juncture, not enough cards have been returned to the union representative to warrant moving forward with the effort.

MAX PADILLA

SADIE HOUSBERG

Comments