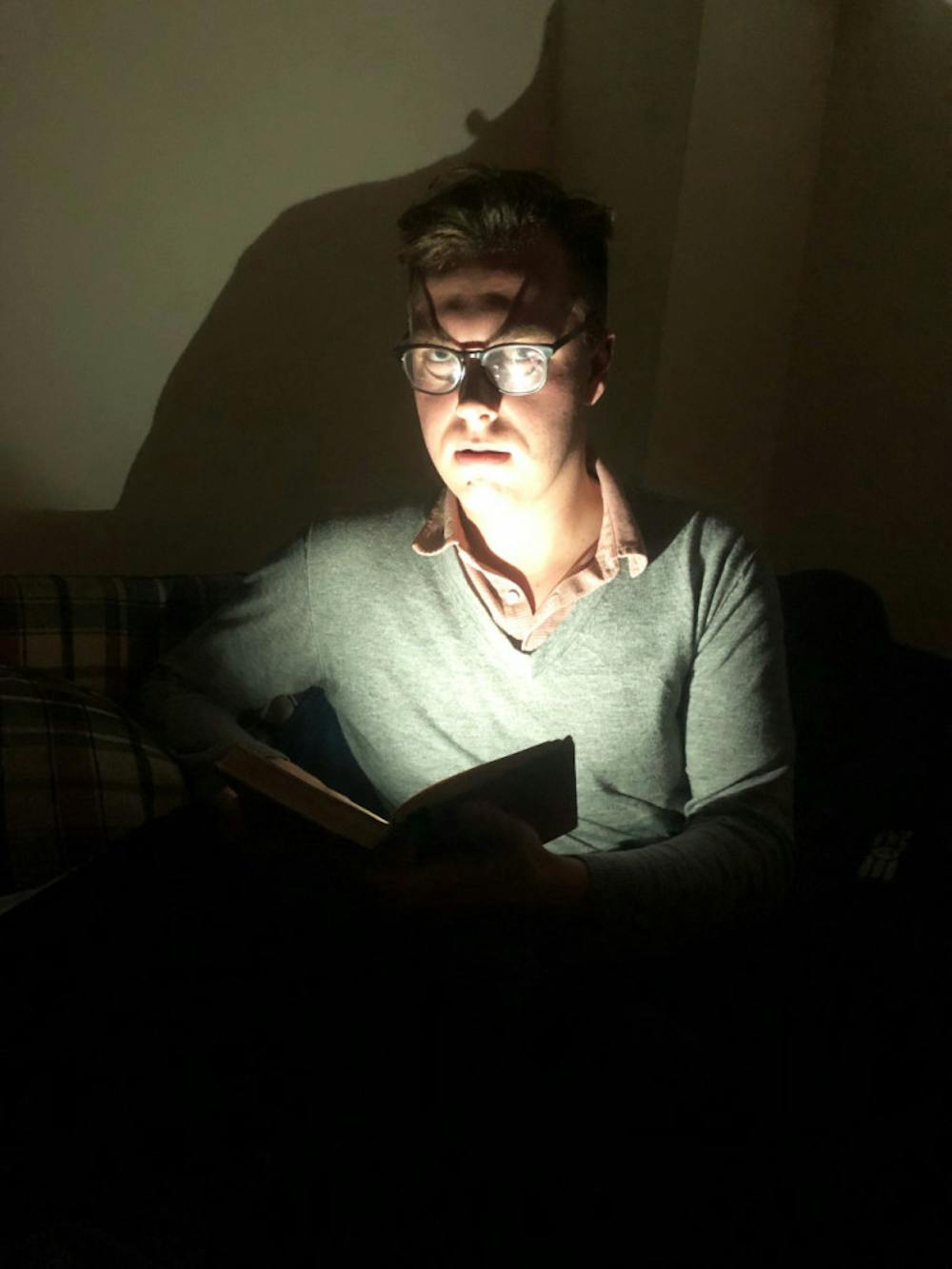

For the bookish among us, Halloween is a perfect time to revisit some of the spookiest tomes ever written. Brace yourselves for my top three fear-inducing books of all time. Don’t read this article alone.

I’m giving third place to Ford Maddox Ford’s “The Good Soldier” (1915). The novel tells the story of four early 20th-century couples: two hopelessly naive Americans, and two world-weary Brits. John Dowell, the American narrator, tries to make sense of his shattered world after discovering that his wife had a long-term affair with Captain Edward Ashburnham, Dowell’s only friend. Meanwhile, Briton Lenora Ashburnham schemes against her philandering husband.

In a sinister plot twist, Ford even adds one or two possible murders. I write “possible” since Ford’s protagonist is a confused, laughably unreliable narrator. Consider this rambling passage: “I don’t attach any particular importance to these generalizations of mine. They may be right; they may be wrong; I am only an ageing American with very little knowledge of life.” Beneath Dowell’s bumbling language lies unnavigable darkness.

Psychological horror does not often feature in romantic novels. The most heart-stopping scene in “Pride and Prejudice” (1813), for instance, is when Jane Bennet gets a bad cold. But “The Good Soldier,” despite its lusty beginnings, slowly becomes an utter nightmare. “I know nothing — nothing in the world — of the hearts of men,” relates Dowell. “I only know that I am alone — horribly alone. No hearthstone will ever again witness, for me, friendly intercourse.” Note the use of the word “intercourse.” Ford writes about sex in the same way that horror writer H.P Lovecraft characterizes the cosmic entity Cthulhu in the eponymous short story: as an ominous, primordial reckoning.

“The Good Soldier” ends with Nancy Rufford, the Ashburnham’s ward, descending into madness. After Nancy falls for Captain Ashburnham, the four main characters unite in banishing her to India. She spends the rest of her days in a madhouse, murmuring “Credo in unum Deum omnipotentem” [I believe in one all-powerful God] over and over again. Like Nancy’s recitation of the Nicene Creed, “The Good Soldier” will haunt you long after you have reached the story’s end.

My runner-up is “The Woman In White” (1859) by Wilkie Collins. T.S. Eliot wrote, in the introduction to a 1928 edition of the book, that Collins’s other great novel, “The Moonstone,” is “the first, the longest, and the best of modern English detective novels in a genre invented by Collins and not by [Edgar Allen] Poe.” “The Woman In White” has even more sleuthing than “The Moonstone” (1868). But while the latter book has a comic tone, “The Woman In White” invokes pure dread.

The novel’s opening scene is simple, but spooky. Walter Hartright, an impoverished drawing teacher, walks through the streets of London late at night. From out of the fog appears a young woman clad in pale tatters. She asks for some directions, but then suddenly flees. We learn that her name is Anne Catherick, and that Anne has recently escaped from a ward for the criminally insane.

Some months after this strange encounter, Walter falls in love with Laura Fairlie, a wealthy art student. All is well for a bit, but developments arise. For one, Anne Catherick is stalking Walter. For another, Laura gets engaged to Sir Percival Glyde, an old rake who values his fiancée’s dowry a bit too much.

I shall divulge no more of the novel’s plot; “The Woman In White” is too good a book to be spoiled. Let us suffice to say that identity theft, mail fraud, false imprisonment and a nationalist Italian spy ring all feature in Collins’s blood-curdling narrative.

What makes Collins’s novel truly terrifying, though, is its main villain, the plumply evil, wickedly charming Count Fosco. The Count likes to sing church hymnals, drug unsuspecting heiresses and murder for money. In a weirdly funny scene, he even talks to his pet mouse. “...And then, Mouse, I shall doubt if your own eyes and ears are really of any use to you. Ah! I am a bad man... I say what other people only think, and when all the rest of the world is in a conspiracy to accept the mask for the true face, mine is the rash hand that tears off the plump pasteboard, and shows the bare bones beneath.” Cynical and sadistic, Count Fosco raises the novel’s stakes to a fever pitch. Move over, “Rebecca” (1938) — “The Woman In White” easily dwarfs all other English country-house thrillers.

I’m giving some honourable mentions before I unveil my top winner. “The Raven” (1845) by Edgar Allen Poe has not lost its neurotic punch over the years. Try reading the poem aloud for optimal spookiness — Poe’s jumpy style suits the spoken word perfectly. Another great scary read is Donna Tartt’s “The Secret History” (1992), a bleak character study about six students at a liberal arts college in Vermont. (If you are a fan of Vermont horror stories, I also recommend our article on the vandalism at Atwater A and B).

But Agatha Christie’s “And Then There Were None” gets my Spooky Story Gold Medal. Unlike my third and second place winners, Christie’s sparse novel can be read in one sitting. It tells the story of ten perfect strangers who are stuck on an island vacation resort. One of the guests, we discover, is a psychopathic murderer. Who could the bad guy be? Phillip Lombard, a dapper gun-for-hire? Thomas Rogers, the creepy butler? Just when you think you know who the murderer is, Christie kills off your prime suspect.

Christie gives a ghostly aura to “And Then There Were None.” In particular, the novel’s dream sequences are unsettling: they contain flashbacks that foreshadow the grisly fates of Christie’s characters. In an eerie scene, an old woman speculates that the murders are a divine judgement. She is right, in a sense: all the people trapped on the island have their own demons to confront. Even before the novel’s climax, it becomes clear that Christie’s characters are all going on a one-way ticket to Hell; the murderer merely expedites their journey. Read “And Then There Were None” once for the scary bits, and then read it again just to marvel at Christie’s athletic prose.

So that’s my list. And, yes: I am aware that I have neglected some of the horror genre’s usual suspects. Stephen King, Mary Shelley and dozens of other fine writers did not make my final cut. I suppose that is because I don’t find fantasy a particularly exciting genre. “It” (1986) and “Dracula” (1897) have fangs galore, but the mundane wickedness of “The Good Soldier” is to me much more terrifying. The books that get under my skin understand the demons of the human condition; true scariness confronts the monsters of everyday life. The horror, dear Brutus, is not in our Count Draculas, but ourselves.

Don't read these books alone

COURTESY PHOTO

Comments