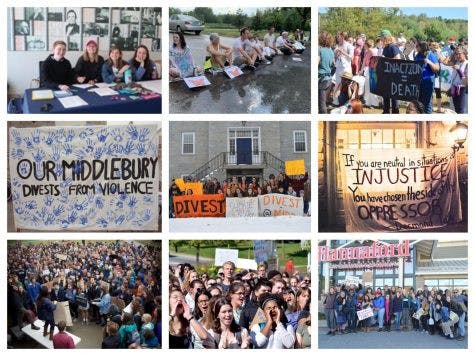

Snapshots of campus activism through the years point to a robust culture of campus activism at Middlebury. But still, report student activists, obstacles remain for those hoping to effect change. (FILE PHOTOS)

“Middlebury College has never been considered a hotbed of political activity,” reads an article published in The Middlebury Campus from November 2002. “Its own students describe the atmosphere as ‘sleepy,’ ‘detached,’ and ‘bubbled-in.’ Those who dare to shatter the quiet are a minority that is sometimes scorned for disrupting this remote paradise. ‘Protest’ is something that is debated; ‘activism’ is something that occurs elsewhere.”

The author noted later in the article that this trend was already changing. Now, 17 years later, most students would likely disagree with the notion that Middlebury students are apolitical.

In the past few years alone, student activists, leaders of campus extracurriculars, and campaign organizers have built websites to direct students to resources surrounding sexual health (go/sexysources); they have also successfully petitioned the college to become a “sanctuary campus” after President Donald Trump’s decision to rescind the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals. Notably, after nearly a decade of work, the student-led effort by Divest Middlebury culminated with Energy2028, a commitment from the college to divest its endowment from fossil fuels companies over the coming years.

These success stories are the glossy stuff of press releases. But the long-winded road to change — enacted by an ever-changing student body amid a minefield of obstacles — is anything but straightforward.

Isolation and insulation: Student activism in the “Middlebury bubble”

The college’s location in rural Vermont can make some students feel disconnected from national and international political issues. Many students reference “the Middlebury bubble” to describe the seemingly impermeable membrane that blocks students from the “real world” and to some, seems to propagate homogenous ideologies.

Annie Blalock ’20.5, current president of Feminist Action at Middlebury (FAM), said that Middlebury’s relative isolation may contribute to the feeling that students are confined in how they can respond to larger issues. Blalock joined FAM to combat this feeling of voicelessness.

COURTESY OF SPECIAL COLLECTIONS

An article from a November 2002 article in The Campus.

An article from a November 2002 article in The Campus.

“As time passed during my first semester, I felt the weight of the Middlebury bubble every day [in] that new inhumane policies were introduced or protective legislation taken away,” Blalock wrote in an email to The Campus. “I turned to FAM to stay educated about current events and take action in an accessible, fun environment.”

Madison Holland ’21 has been involved with the college’s branch of Amnesty International, an international organization that focuses on human rights, and Juntos, a campus organization that advocates for quality working conditions for local farm workers. She said she enjoys building relationships with members of the community through her activism.

“It’s important to realize the broader picture, that that there are other people off campus with real lives and real stories,” Holland said. “Especially considering we’re only here for four years and there’s a world out there that we’re going to have to encounter eventually, so we might as well start now.”

The college’s small size has other impacts as well: the activist community is very insular, according to Taite Shomo ’20.5 and Grace Vedock ’20, two students with long resumes of campus activism.

Amongst other initiatives, Shomo and Vedock are the organizers of It Happens Here (IHH), a storytelling event that draws attention to campus sexual assault. They also helped coordinate The Map Project, which documents locations of incidents of sexual assault on campus with red dots on a map. Last spring, Shomo and Vedock helped organize the peaceful protest that was scheduled to occur during the Ryszard Legutko lecture that was set for Wed., April 17. The lecture and the protest were unexpectedly cancelled by administration due to “safety risks,” which were left ambiguous when first announced.

“A lot of people who are leading activist charges, it’s the same group of people over and over,” Shomo said. “What I find very frustrating is that I think the Middlebury population constructs itself as aware and involved and liberal. But in my experience, when we have asked people to step up and be part of things, they’re not there.”

According to Shomo and Vedock, the core group of activists — those who organize most of the major protests and campaigns on campus — is so small that students have created various group chats to connect with other students who are committed to using activism as a tool of social change.

“Student activism is difficult for so many reasons. It takes so much time and so much emotional energy. Usually the people that are involved in certain initiatives have been directly affected by those initiatives, ” Vedock said. “If the burden is on the affected population to change the culture, it can be extremely bleak.”

Vedock said that student activism can be “exhausting,” and Shomo said that doing activism takes energy away from friends, school, family and her own health. This is a common constraint that many students face when organizing changemaking efforts on campus: they are students first, with the primary goal to obtain a degree.

With time already a scarce resource in college, it can be difficult to mobilize students for a particular campaign or event.

“Students are stakeholders in so many different areas of campus, so I think that’s a struggle — not necessarily in getting people to voice their support but to act on that support,” Holland said.

Student activists also must navigate the rules set by administration for student organizing, a process which Blalock said is “unnecessarily burdensome.” The consequences for violating college policy, however, can be serious.

Prior to the visit of His Holiness the Dalai Lama to Middlebury in 2012, five students who dubbed themselves the “Dalai Lama Welcoming Committee” circulated a mock press release to students, faculty and media outlets announcing that the college would divest from industries of violence. The students were charged and ultimately found guilty by the Community Judicial Board during an open hearing and were given a reprimand, but were not subject to any official college discipline.

CAMPUS FILE PHOTO According to The Campus, the student taking down the flags in the photo above, Anna Shireman-Grabowski ’14.5, was "one of the College’s most passionate student activists."

In 2013, a student was suspended for one year for uprooting thousands of flags that were put in the ground as part of a memorial to commemorate the victims of 9/11. The student claimed that the memorial sat on top of an Abenaki burial site, and should be treated with respect.

More recently, when students protested and shut down the 2017 lecture of controversial sociologist Charles Murray, the college punished 74 students with sanctions ranging from probation to official college discipline. Students were accused of violating the section in the Student Handbook that prohibits “disruptive behavior at community events or on campus.”

“If we have to be afraid of being suspended because of engaging in protest, that’s a very precarious situation to be in,” Shomo said.

While some students do not engage with student activism, many feel compelled to act, no matter the risks.

“People don’t engage with activist activities for a variety of reasons — maybe you’re working a job, maybe your course load is so difficult — but for some people it takes an enormous amount of privilege to not be concerned about things or to just not think about things,” Vedock said. “When you’re engaged with these initiatives, you have to ask yourself: Who are you fighting for?”

Changing the world … in just four years

Though students encounter unique challenges when trying to create change, some have identified strategies that have proved repeatedly effective in moving their campaigns forward. Megan Salmon ’21 serves as president of Amnesty International and is the student activism coordinator for Amnesty USA, meaning she oversees all efforts by Amnesty chapters at universities in the state of Vermont. She said incentivizing students can be effective in persuading people outside of the core group of activists to show up to events.

“Whether it’s a musical performance, or it’s interactive, or there’s food, or prizes — it gets them off the couch, basically,” Salmon said.

Holland said coalition building can be an effective way to show that an issue is important beyond one group. Early this month, Olivia Pintair ’22.5 and Hannah Ennis ’22.5 organized the Milk with Dignity campaign at the Hannaford supermarket in Middlebury. The campaign was one of about 20 campaigns across the Northeast that was organized by Migrant Justice, a nonprofit that advocates for economic justice and human rights of farm workers.

“Our organizing included… networking with other groups on and off-campus in order to get as many people as possible to attend the action itself,” Pintair wrote in an email to The Campus.

According to Pintair, Middlebury Refugee Outreach Club (MiddROC), Juntos, Sunday Night Environmental Group (SNEG), a church group in Middlebury, and Standing Up for Racial Justice (SURJ) all “contributed in different ways to the action.” Some members of these groups made signs to display at the event, while others attended the rally. Pintair said activists from Migrant Justice were also present, leading chants in both Spanish and English. They also hand-delivered a letter to the manager of Hannaford at the protest, urging the supermarket to “ensure human rights for the farmworkers behind the company’s milk.”

FILE PHOTO: MICHAEL O’HARA

As a result of the Charles Murray protest, 74 students received punishments from probation to official college discipline.

As a result of the Charles Murray protest, 74 students received punishments from probation to official college discipline.

“I sometimes find student activism challenging on campus with how many different clubs and groups there are at Middlebury, each with their own specialty,” Ennis wrote in an email. “I was really inspired by the action and rally on Nov. 2 at Hannaford because of the way many different student organizations came together for this one cause. I hope to see more events in the future with groups working together.”

Change is slow, Ennis said, and it’s important to “connect with people, create a network, and build outwards.” Students attend Middlebury for four years, but larger structural changes may take longer. According to Vedock, movements must “cultivate institutional memory” to have a degree of longevity.

Divest Middlebury, a movement created to divest the college’s endowment from fossil fuels, has been able to sustain itself throughout several generations of Middlebury students. The movement can be traced back until at least 2012, when the students from the Dalai Lama Welcoming Committee pushed the issue into prominence.

Many activists feel responsible for passing along information and resources to younger students, lest the movement die from lack of participants. Divya Gudur ’21, who has been involved in various environment-focused organizations such as SNEG, the Divest Middlebury movement, and Environmental Council, said that SNEG has a Google Drive folder filled with documents containing information from past events, and that they also have a reliable alumni network.

“Over the recent years we have been more and more intentional about our recruiting efforts and have been working towards making sure that underclassmen feel like they have ownership in the organization and the campaigns,” Gudur said. “SNEG has often struggled with retaining activists not only because of burn-out, but also because there seems to be a dichotomy of you’re either all in or on the outside, and we need to make space ... for all levels of participation.”

Students have also found they can build institutional memory by collaborating with a group of people who will remain at Middlebury much longer than themselves: faculty.

Last spring, research assistants for the Gender, Sexuality, and Feminist Studies (GSFS) Department, Ruby Edlin ’19.5, Elizabeth Sawyer ’19 and Rebecca Wishnie ’20, gave a presentation titled “Collective Memory, Collective Action: Building a Digital Archive of Student Activism” which explained the ongoing efforts to build a digital feminist archive of campus activism. The project was supervised by Sujata Moorti, who was the chair of the GSFS department at the time, and Karin Hanta, director of Chellis House.

Comments