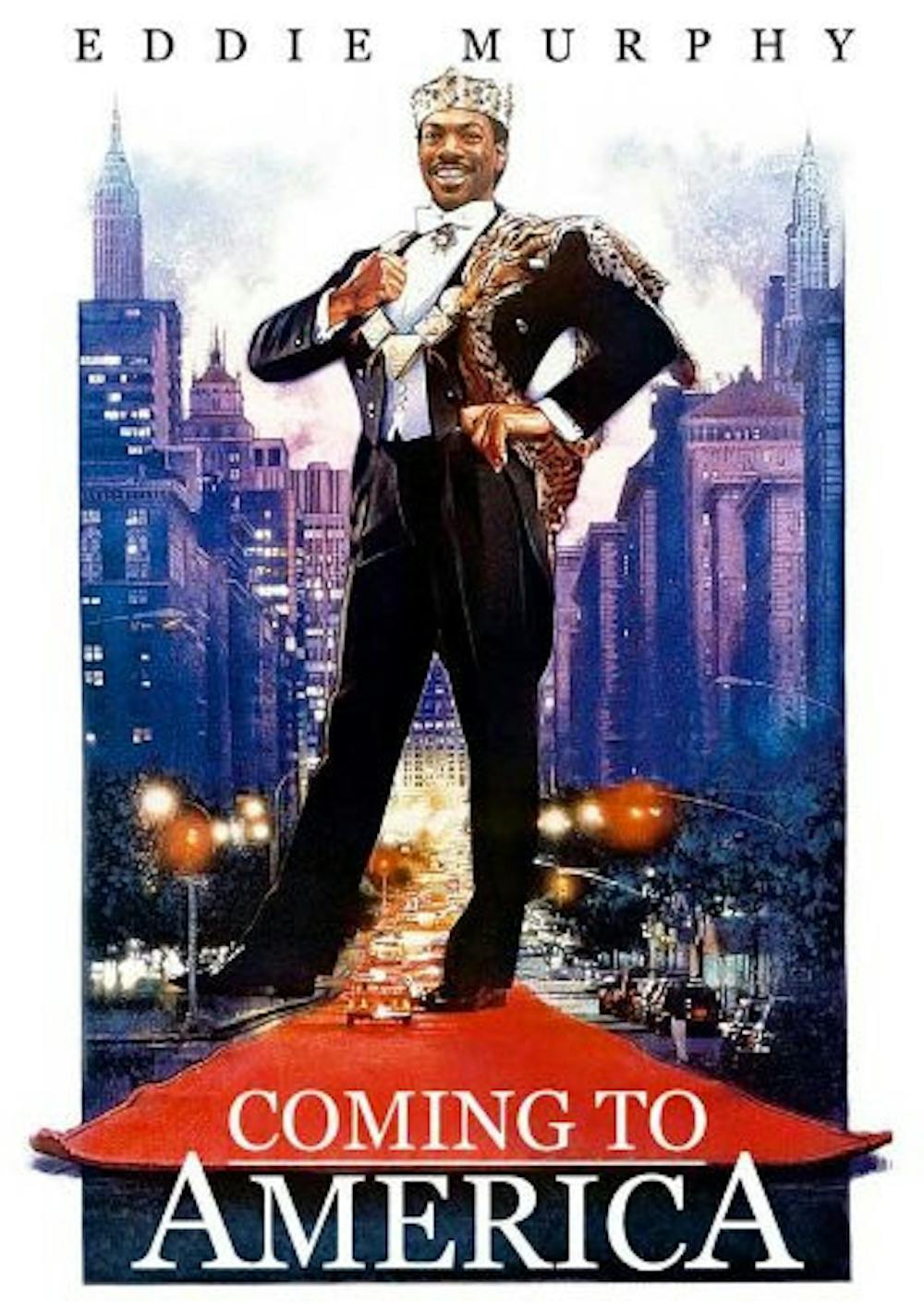

I’m sure many black students on campus will be surprised when I tell them that I first watched “Coming to America,” a bona fide African American cult classic, this year, from beginning-to-end, at age 33, 30 years following its release. I’ll let the shocked gasps and guffaws die down before I go on. *waits.* For those who don’t know, this film, like “Friday” and “The Wiz,” is one many black Americans quote as a demonstration of being part of the “in-group.” Know that “Bye, Felicia!” reference? Yeah, that stems from “Friday.” Sure, I’ve been curious about the film in a lazy sort of way but it wasn’t until “Black Panther” came out that I actually pursued “Coming to America” with any sort of one-mindedness. Why, you ask? Because I knew that “Coming to America” also represented a fictional, African country, “Zamunda,” and I wanted to weigh its representation against “Wakanda.”

Not many African Americans encounter the privilege and opportunity of engaging with African studies or setting foot on the African continent. I have been fortunate enough to do both and for that reason, to some extent, I know how distant from reality the media’s representations of African peoples, cultures, communities and geographies can be. So, part of me actively looks for friction between what is accepted as truth and what I have experienced as truth. You might call it a willful quest for cognitive dissonance — something I recommend for all of you who are being trained in critical thought.

All of this said, let’s talk about the film at hand.

Essentially, “Coming to America,” featuring comedian Eddie Murphy in the height of his popularity, is the story of an African (Zamundan) prince who is bored by the women he finds in his country. They have been trained since birth to please him in any and all ways. They bathe him and if he asks them to hop on one foot and bark like a dog, they do not hesitate to satisfy his request(s). The prince finds this behavior understimulating so he designs a quest of his own in which he abandons his home and heads to Queens, New York to find his “queen”-to-be. His plan, intentionally and comically haphazard, leads him to work in the fast food industry as he feels a need to disguise his riches.

Long story short: he becomes enamored with a local woman and desires to pursue a courtship.

As a feminist, I have some significant discomforts with the patriarchal tropes in the work. However, I must say, if you’re looking for balanced, forward-thinking comedy, it is not Eddie Murphy’s oeuvre you want to search. (Hannah Gadsby’s might work for you. Ali Wong’s is worth exploring. And Hari Kondabolu’s, too, is worth a listen.) I have enjoyed some of Murphy’s works for years — no, decades. But “insensitive,” “crass,” “sexist” and “homophobic” are all befitting of his repertoire. And the further we move into the 21st century, the less we want to take out-moded values with us.

Why does this film remain popular and beloved? The story is “easy” in its predictability; it’s flagrant in its inaccurate cultural representations; it’s extreme in its, well, patriarchy. And apparently that’s what works. Or has worked. The idea that one of “our” beloved cultural films willfully misrepresents African cultures and reduces many African people to caricatures is disquieting to me, and I believe it is ignorance that keeps us from general objection.

How does Zamunda compare to Wakanda? Both represent worlds of extravagance and wealth. Both depict African peoples as living in close harmony with wild animals. Both seem to have a reverence for patriarchal kingdoms and palatial residences, tropes that Hollywood cannot seem to shake. Wakanda, however, elevates women and their roles in the kingdom with the royal security force of the Dora Milaje; it values the latest uses of progressive technology; and the king’s heart is unequivocally engaged with his subjects’ well being. I wonder what a fictional African country will look like on screen in 2048? Maybe there will be no palace. Maybe there will be a neighborhood. Maybe the protagonist’s gender and gender expression will be less central to the plot. Maybe the protagonist will be *gasp* African. Overall, I think it’s important for black people to watch “Coming to America” as it is a historical document that has meaning when it comes to the black canon of film. However, ultimately, I hope we will use it as a measuring stick to demonstrate how far we’ve come 30 years hence.

For more works from the black cinematic canon, see “The Color Purple” or “Roots.” Or consider some television classics like “The Jeffersons.”

Literatures & Cultures Librarian Katrina Spencer is liaison to the Anderson Freeman Center, the Arabic Department, the Comparative Literature Program, the Gender, Sexuality & Feminist Studies (GSFS) Program, the Language Schools, the Linguistics Program and the Department of Spanish and Portuguese.

The Librarian Is In

Comments