Like the class of 2019.75, the class of 1918 was forced to leave Middlebury early. Just before the end of the fall 1917 term, The Campus reported emergency schedule changes that would reduce Christmas vacation by a week and move the class of 1918’s Commencement from June to early May of the following spring. This was to allow students to return home to their farms in time for the spring planting season. Farm workers, as with all types of workers, had been in short supply since the U.S. joined the war in Europe in 1917.

This was just one of many changes that the war would require. The college was raising $400,000 to secure it against wartime changes just as the men’s college senior class was “suffering depletion continually” as “one by one they drop out” to enter military service, according to a December 1917 Campus report. Nonetheless, campus life carried on. KDR continued to hold notable parties. The Campus exchanged heated op-eds about current events.

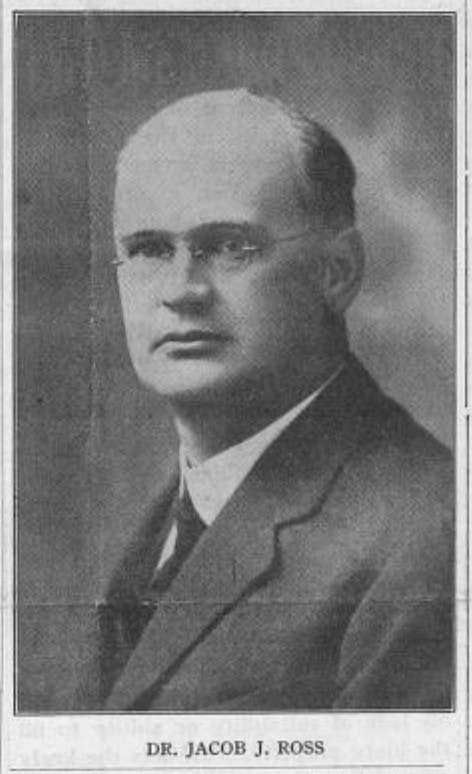

Dr. Jacob J. Ross led physical education at Middlebury in 1917 before enlisting in the Army Medical Corps. He is pictured in the 3 Oct. 1917 issue of The Campus.

Little did they realize what was waiting for them when they returned.

The so-called Spanish Flu had been spreading across Europe since the spring. Vermont Secretary of Health Charles Dalton, like many of his counterparts across the U.S., knew it was only a matter of time before the deadly influenza pandemic would reach his state. Finally, it hit Vermont in September 1918, just as students were returning from their homes across the country. By Sept. 21, 40 “Middites” were sick. Five days later, student Charles Thompson had died. His death was followed a week later by that of another student, Charles Dana Carlson. The College implemented a quarantine and, a few days later, the state banned all public gatherings.

Initially, college officials were not overly concerned with the cold-like symptoms displayed by students. Yet, they quickly reversed course as Thompson’s health rapidly declined. The college converted Hepburn Hall, already commandeered for the new Student Army Training Corps (SATC), into an infirmary. Townspeople had set up an armed guard to ensure that students stayed on campus. The town itself was struggling to meet the medical needs of its residents, ultimately leading to a high death rate.

“[W]ires to Middlebury from New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and other states nearby were kept hot with anxious messages,” reported The Campus. “[F]athers and mothers came to town, and all was alarm.”

Middlebury’s quick and thorough response proved crucial; one student complained that six doctors visited her in a single morning. The (delayed) first issue of The Campus on Oct. 16, 1918 reported that the quarantine might soon be lifted. In the meantime, quarantined students were entertaining themselves: Marion Young, the physical director of the women’s college, organized daily hikes, exercises and soccer games for the residents of “Pearsons and Battell Cottage.” The men’s college organized an intramural football game to replace the canceled game against Williams. Classes resumed on Oct. 25.

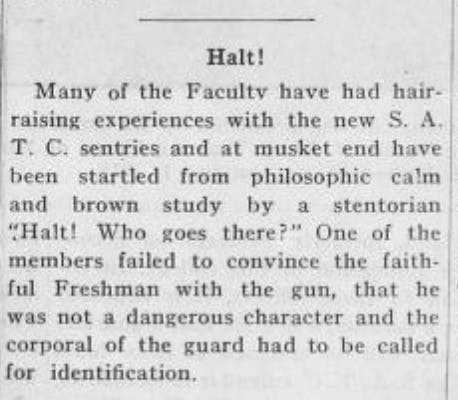

An excerpt from the 16 Oct. 1918 issue of The Campus recounting a faculty member's experience with the SATC.

Despite two deaths and the “military quarantine,” the flu wasn’t the only news story of the day. The SATC had taken over Starr and Hepburn halls. Their Oct. 1 induction exercises took place in a modified, pandemic-response form from the steps of a one-year-old Mead Chapel. Armed, uniformed students could be found patrolling campus day and night for the rest of the semester.

Effects of the war were felt in more subtle ways as well. A myriad of fundraisers, including the continuing endowment fundraiser, the United War Work Campaign, and a collection to eliminate The Campus’s debt, were continuously promoted — all had a connection to war disruptions. Those who remained on campus wished they could “get into the game” in Europe, as a Nov. 1918 Campus editorial read (FOMO, apparently, was as strong then as it is now).

Nonetheless, the college was slowly regaining a sense of normalcy. Although November’s Charter Day festivities had to be reduced, quarantine was lifted only two days later. This prompted an impromptu “visitors’ day on the Hill,” full of friends and family who were finally allowed to visit students.

By the next week, rumors began to spread of peace in Europe. Lieutenant Miles Jones, commandant of the Middlebury SATC, banned the SATC from celebrating until the official declaration of peace the following Monday, Nov. 11. Former college president Ezra Brainerd gave the benediction at chapel services that day. Classes were canceled and the study body flooded into town to celebrate. The troubles of this unusual semester seemed to be firmly in the past.

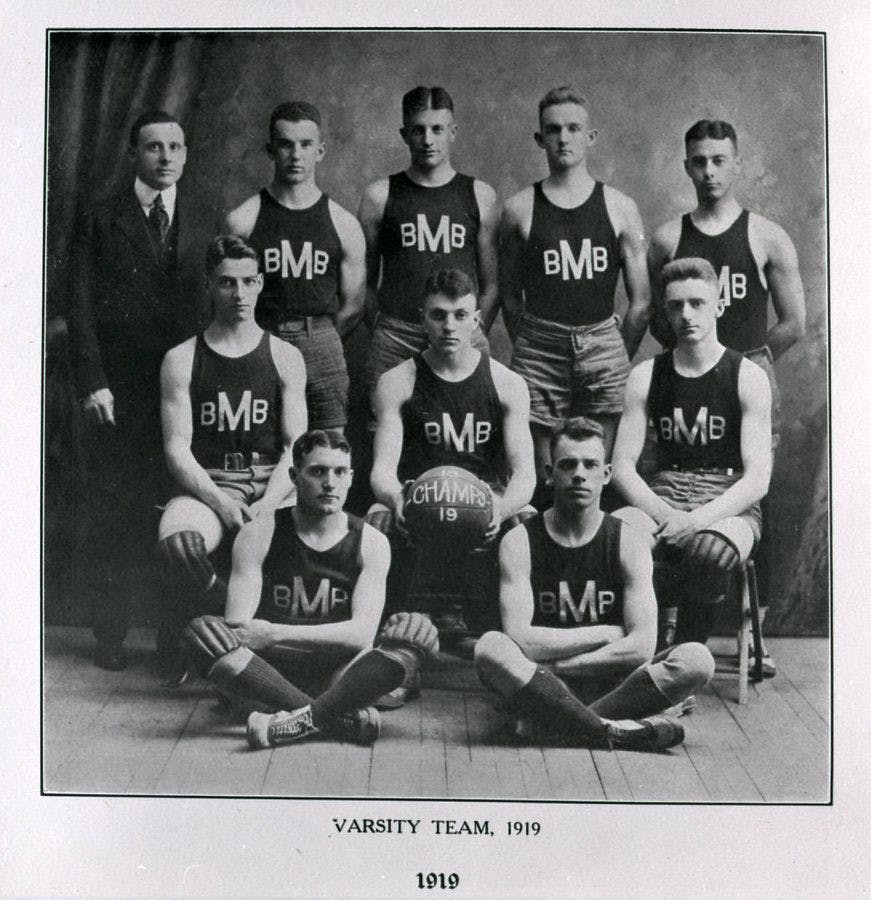

A team photo of varsity men's basketball in 1919.

Now in 2020, as we wait for stay at home orders to end, for vaccines to be developed, for good news regarding our summer and fall plans, we can find comforting words in a December 1918 Campus editorial. “Middlebury faces almost daily changes. It is with a feeling of wonder as to what will come next that we greet each day and it is not strange that under such conditions the student body should be unusually restless and undecided.” Even after the war ended and the campus recovered from the pandemic, change was the rule of the day.

This isn't Middlebury's first time dealing with a pandemic

COURTESY OF SPECIAL COLLECTIONS

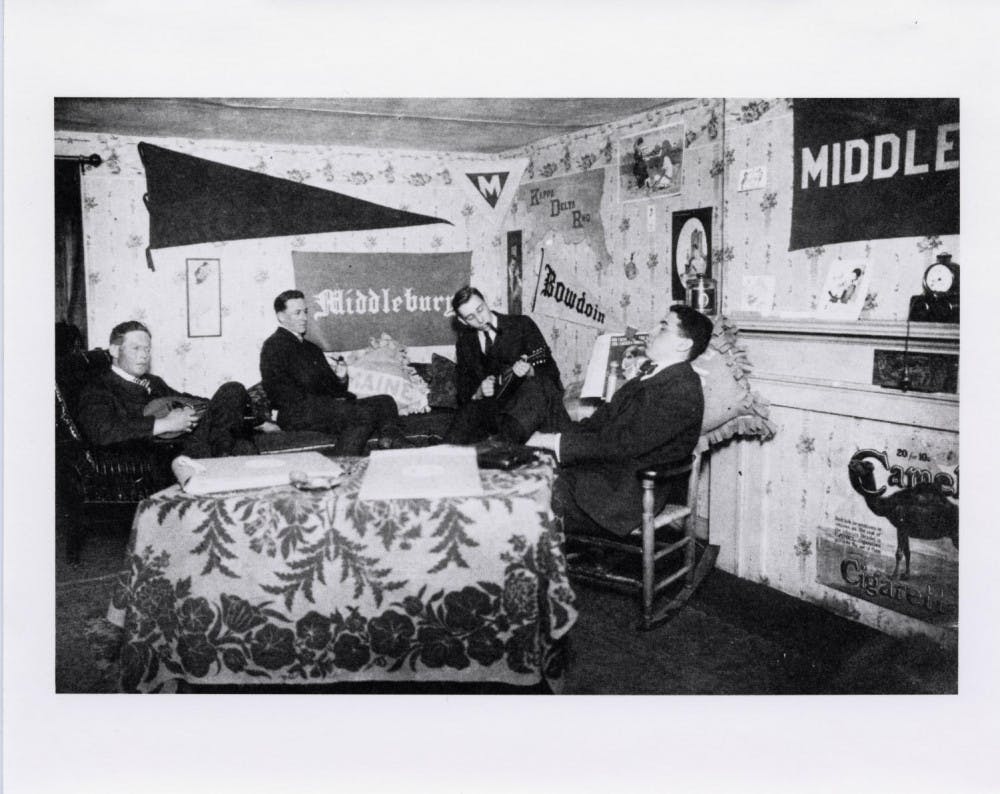

Four students sit in a dorm room in 1918.

Four students sit in a dorm room in 1918.

COURTESY OF SPECIAL COLLECTIONS

COURTESY OF SPECIAL COLLECTIONS

COURTESY OF SPECIAL COLLECTIONS

Comments