Fifty years ago today, students, faculty, staff and administrators crowded together in the pre-dawn light to watch a fire consume Recitation Hall, a temporary building behind what is now Carr Hall. Earlier, at 4:15 a.m. on Thursday, May 7, 1970, a student doused rags in gasoline, placed them against the base of the building and set them alight. The flames engulfed the wood-frame structure at the height of the 1970 student strike over the Kent State shootings and Vietnam War.

While it later emerged that the arsonist was not politically motivated, the fear and tension ignited by the event epitomized the emotion and turmoil on campus and across the nation.

The Campus spoke with former student leaders and activists, faculty, and administrators from the 1970 strike about the triumphs, pitfalls and lasting legacy of the strike and the surrounding years of anti-war organizing.

The Strike

Just three days before, on May 4, protests against the Vietnam War and the bombing of neutral Cambodia engulfed Kent State University. The Ohio National Guard was called to intervene, and in the ensuing chaos, used live rounds on the students, killing four and injuring nine others.

The deaths of affluent, white college students engrossed the nation, bringing home the horrors of war to many in a way the far-off deaths of working class Americans and Vietnamese civilians had not. Calls for a national student strike spread like wildfire across college campuses. Five hundred miles away, the spark of radical anti-war activism finally reached the sleepy town of Middlebury.

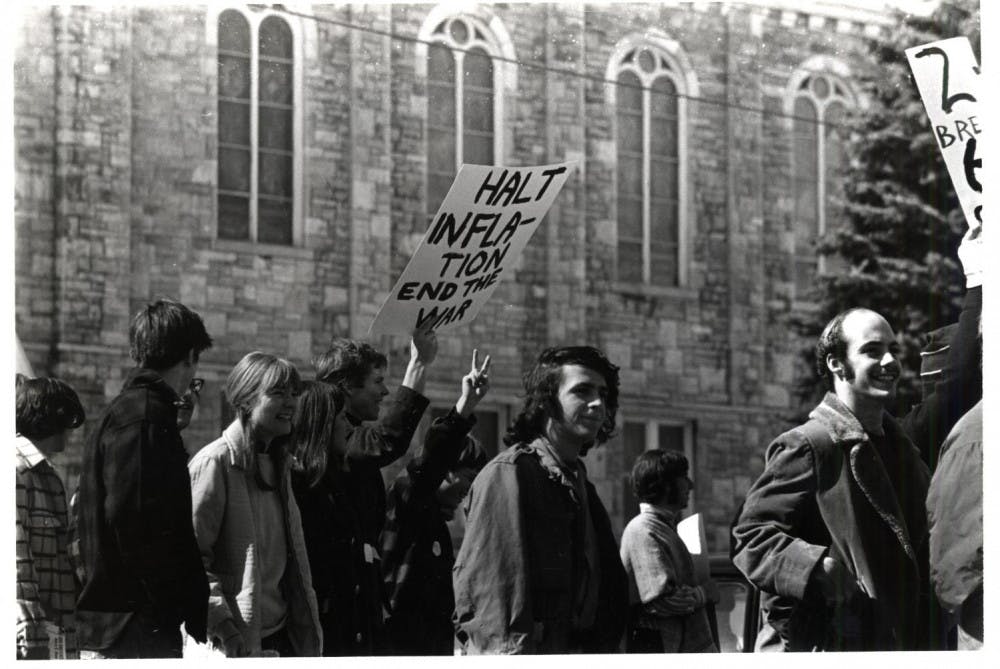

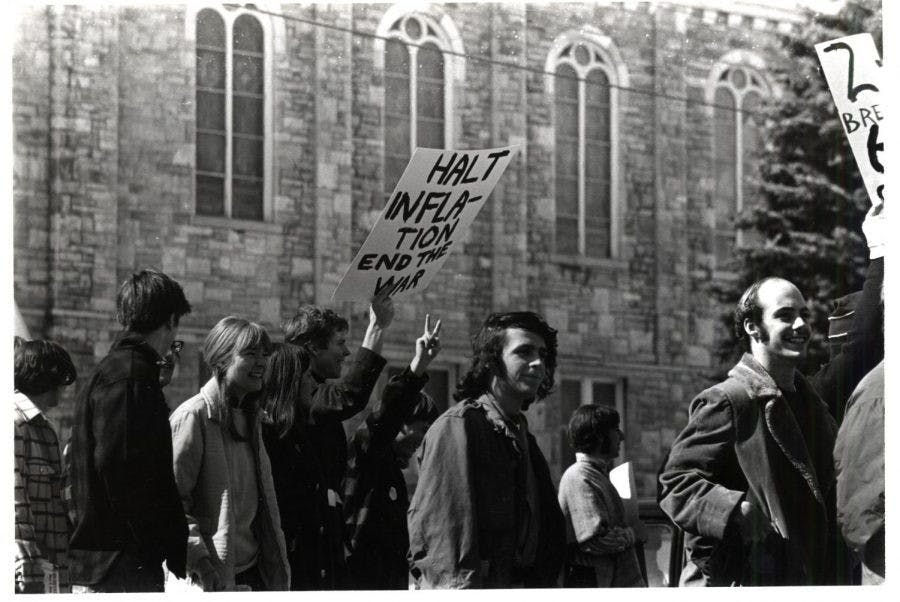

Protesters gathered against the Vietnam War during the March 1970 student strike.

“For six years, now, the flood waters of frustration and alienation and hopelessness have been rising behind the dam,” reads an article from the 1970 Middlebury summer newsletter. “The shooting down of the Kent State demonstrators finally cracked the facade, and all of this accumulated despair poured forth.”

For Howard Burchman ’73 and his band of fellow student activists, May 4 was a night of frenzied activity and organizing. In the WRMC-FM college radio office, Burchman manned the teletype, a machine that sends and receives typed messages, to follow the news coming out of Kent State and traded phone calls with student organizers across the country to coordinate political action at Middlebury. Students covered campus sidewalks with graphics calling for a strike and superglued padlocks on classroom doors so no one could attend class the next morning. At 7:00 a.m., Burchman called Dean of Students Dennis O'Brien to inform him that the students were striking.

By midday, the College Council and faculty had voted and approved a resolution to suspend classes for the rest of the week, both to grieve and memorialize those killed at Kent State and to protest the war in South Asia, joining over 800 colleges and four million students nationwide in the largest student strike in U.S. history.

That evening, students packed into Mead Chapel for a memorial service honoring the four dead students and for the first rally of the strike, which began immediately afterwards. Burchman recalls the space overflowing with bodies as 1,000 students crowded into the aisles of the chapel, designed to hold only 700. The choir sang “Absalom,” a haunting hymn whose lyrics poignantly encapsulated the grief, shock and anger of the student body (“When David heard that Absalom was slain, he went up to his chamber and wept, and thus he said, ‘O my son, Absalom my son, would God that I had died for thee!’”).

Students demanded that the college end its complicity with the U.S. military by removing the Reserve Officers Training Corp (ROTC) from campus; called for the federal release of political prisoners, including jailed Black Panthers; and urged for an immediate withdrawal of American troops from South Asia.

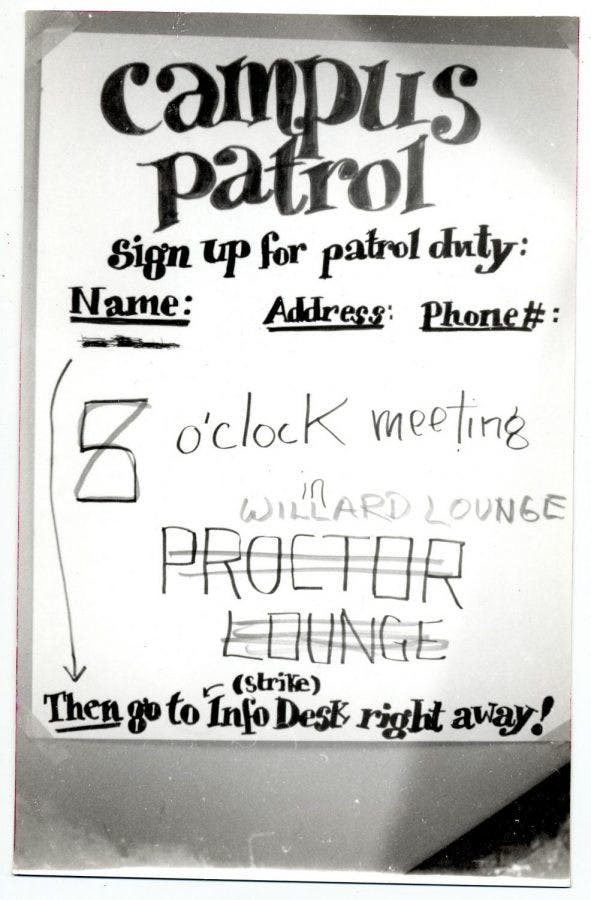

Throughout the week, students spent their days attending teach-ins, workshops and rallies to learn about the war, the draft and Black Panthers. Students marched through Middlebury Union High School to “liberate” the high schoolers and inspire political action. Activists canvassed throughout the town, engaging residents in conversations and aiming to educate the conservative-leaning community about the anti-war cause, according to Steve Early ’71. After the burning of Recitation Hall on May 7, many spent their nights patrolling the campus to prevent further destruction and to avoid the widespread violence witnessed on college campuses nationwide.

Poster at Middlebury College during the May 1970 student strike.

The town residents feared similar violence, and the fire seemed to only reaffirm those fears, causing tension to emerge between the campus and community. In an effort to improve public relations, Obie Benz ’71 organized a group of students to stay in Middlebury over the summer. The students engaged in community service work to try and mend the town-gown relationship and reassure locals that Middlebury students were not like the violent anti-war radicals frequently featured on their TVs.

Results

Classes resumed on May 11 with academic exceptions made for students who took the rest of the semester off to protest the war. The College Council, faculty, and student body voted to broadly affirm the national strike goals, substituting the demands of national leaders for more moderate language.

The Middlebury administration worked hard to maintain Middlebury’s reputation and reassure parents, alumni and community members that the college-wide activism was moderate in tone. Middlebury President James Armstrong never referred to the events as a “strike,” describing it instead as “suspending normal activities,” being “in extraordinary session” and deciding whether or not to “resume classes,” according to Baehr. In the summer newsletter to parents, the college framed the strike as “a united searching — by students, faculty, and administrators — for the most useful set of responses to the national situation.” The newsletter failed to mention Black students’ efforts to raise issues of race, or calls for solidarity with the Black Panthers. That year set the then annual fundraising record high of $272,000.

Still, the strike was a catalyst for widespread student anti-war action at Middlebury in the years that followed. Radical Education and Action Project (REAP), founded by student activists Early and Burchman the following fall, brought speakers to campus and hosted rallies, with the goals of inspiring political action and thought through education.

Burchman recalled groups of students routinely burning draft cards outside of Proctor Hall in shows of public defiance against the war. Burchman himself faced disciplinary action when he protested Navy representatives publically advertising beside the cafeteria line. He set up shop next to them and projected images of napalm-ravaged villages and mutilated Vietnamese children until the Navy representatives left.

“It's not like the student strike happened once and there was no more unrest,” Burchman said. “The great mass of Middlebury returned into its slumber, but there was an activated core of hundreds of students who remained very very committed.”

While immediate responses to the strike and student anti-war organizing at Middlebury may have been tepid, students’ efforts did make a long term difference. O'Brien cited the strike as a major reason for the college’s ultimate decision to remove the Military Studies Department as a credit-bearing program and relegate ROTC to an off-campus extracurricular in 1976.

“The collective activity, unexpected and unprecedented in scale, put pressure on lots of other people [like Armstrong], drew them in, and made them part of the process of seeking solutions to the situation,” Early said. “Students became a conscience for people in positions of authority, including elected leaders and heads of institutions.”

On a national level, many consider the widespread student activism on college campuses instrumental in pressuring the U.S. government to withdraw from Vietnam in 1973.

Issues of Inclusion

Anti-war efforts at Middlebury struggled to include more diverse voices.

While the killing of four white students at Kent State galvanized the campus into widespread action, the shooting of Black students by the National Guard, resulting in two dead and 12 injured, at Jackson State University in Mississippi just 11 days later hardly registered a response at Middlebury. Efforts by Black Students for Mutual Understanding (BSMU) to organize around the shooting and raise consciousness around the Black Power movement went largely ignored by the student body.

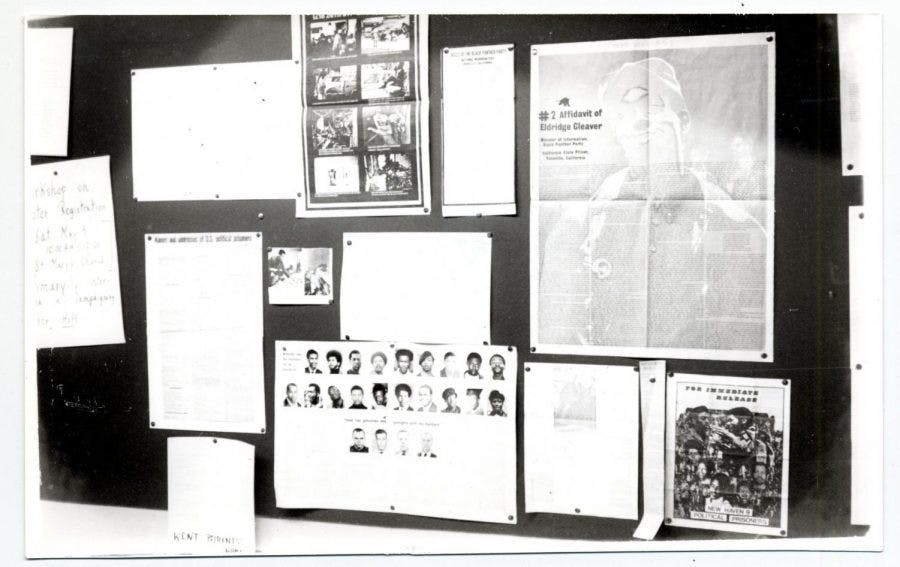

Bulletin board at Middlebury College during the May 1970 student strike, displaying material from student organizers, the Black Panther Party, etc.

“The death of the four Kent State students was a very tragic event for Kent State and the parents of those students,” read the BSMU position paper published May 6. “However it would be hypocritical of this organization and its members to pretend that these deaths have rendered us emotionally bankrupt; for many of us, and the vast majority of Black people, death and suffering has become a very real part of life.”

“We barely paid even lip service to the urgent issues Arnold [McKinney ’70, the leader of the BSMU,] and others were trying to have us see during the strike,” wrote Kaarla Baehr ’70 in an email to The Campus. “Not surprising given the time and place, but painful.”

Just as Black activists were excluded from the mainstream conversation, women were sidelined as men took center stage in the anti-war movement at Middlebury and beyond. Baehr, the Student Senate president at the time, was the only prominent female voice during the strike.

When she came to the stage to speak to the assembled crowd at Mead Chapel on May 5, the entire rally had to pause for several minutes as she attempted to lower the microphone positioned well above her head. That struggle was indicative of an entire movement structured around an assumption of male leaders, Baehr said.

The summer newsletter to parents made that divide even more apparent.

“Striking blonde reads a letter to her teachers explaining why she was quitting for the rest of the year,” read an article detailing the chronology of the strike.

Class also divided student protesters. Calls to shut down the campus for the rest of the semester failed to inspire many low-income and first-generation college students, who did not want to jeopardize their hard-won and expensive education, according to Baehr. While some students took the summer off to protest the war, Early, a dedicated activist and major organizer of the strike himself, had to start work flipping burgers at McDonalds immediately after finishing his finals in order to afford his next year at Middlebury.

Learning to Lead

The gaps in representation during the 1970 strike gave rise to opportunity. Torie Osborn ’72 transferred to Middlebury in the fall of 1970 after being inspired by the anti-war activity of the previous fall. She became one of the most visible figureheads of the modern women's movement at Middlebury, helping eliminate curfews for female students, advocating for access to birth control and organizing an abortion underground to Montreal where it was legal in the days before Roe v. Wade.

She learned how to organize and lead as an activist through her anti-war activism at Middlebury. Those skills helped shape her decades-long career as a queer feminsit activist, which has included serving as the executive director of the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force and a term as senior advisor to the mayor of Los Angeles, focusing on reducing homelessness and poverty.

“I was used to being one of thousands of followers. When I got to Middlebury, I learned how to be a leader. I learned how to organize,” Osborn said. “The skills that I learned and the passion that was reinforced at Middlebury for social justice activism has shaped my whole life.”

Many of the organizers of the 1970 strike and subsequent anti-war activity went on to lead lives as prominent activists, like Early, who is known as an organizer, union representative labor activist, lawyer, and author. He said his time at Middlebury taught him how to successfully organize action and the importance of patience in long-term social justice efforts.

Burchman was a freshman in 1970. Leading anti-war activism over the next three years, he learned how to take advantage of the power of crises to galvanize the masses and create longstanding positive change. He later used those lessons to fight the ’80s HIV/AIDS epidemic in New York City, advocate for community health and residential care and work to develop solutions for homelessness across the country. He is now working remotely to advocate for the homeless in Nebraska in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic.

“[The strike and anti-war activism at Middlebury] gave me a direction in life. The war gave me an understanding of the basic question: Who benefits?” Burchman said. “I’ve been able to have a wonderful professional career orientated towards issues of social justice... that I’m so grateful for. It gave me a great life.”

Beyond the individual lives of Middlebury graduates, the 1970 strike and anti-war activism of the late 60s and early 70s has left an indelible impact on the landscape of education nationwide.

In a Jacobin article, Early cited student walkouts over the Iraq invasion, Parkland shooting and climate change as echoes of the 1970 strike continuing to influence national politics.

“The memory of [the student strike] hangs on and hangs on,” said O'Brien. “The effect of that one moment, that one week, has impacted into the student DNA [at Middlebury and beyond].”

Sophia McDermott-Hughes ’23.5 (they/them) is an editor at large.

They previously served as a news editor and senior news writer.

McDermott-Hughes is a joint Arabic and anthropology and Arabic major.

Over the summer, they worked as a general assignment reporter at Morocco World News, the main English-language paper in Morocco.

In the summer of 2021 they reported for statewide digital newspaper VTDigger, focusing on issues relating to migrant workers and immigration.

In 2018 and 2019, McDermott-Hughes worked as a reporter on the Since Parkland Project, a partnership with the Trace and the Miami Herald, which chronicled the lives of the more than 1,200 children killed by gun violence in the United States in the year since the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shooting in Florida.