Chicken. Sweet potatoes. Vegetables. Chicken. Sweet Potatoes. Vegetables. Over and over again, I filled container after container of food until it became almost robotic, studiously ignoring my grumbling stomach, parched throat and sweaty hands steaming inside my vinyl gloves. There was no time to rest, only time to prepare for students to arrive.

On Sept. 17, I went to work a dinner shift at Proctor Dining Hall to speak to staff and see first hand what it is like to work in the dining halls under the Covid-19 restrictions.

When I arrived at 5 p.m., the area where staff serve food, known to those who work there as “the line,” was full. Three student workers, four full-time staff members and I stood at the ready. It was the most workers one senior staff member, who wished to remain anonymous, had ever seen. For him, it was a welcome relief.

Throughout Phase One, only three staff worked the line most days due to staff shortages. Three people alone had to manage all the normal operations of the kitchen — cooking extra food and refilling the food pans — in addition to all of the new responsibilities that came with Covid-19 guidelines. The typical self-serve buffet style dining is no longer possible due to Vermont-wide Covid-19 restrictions. Instead, dining staff have had to serve students on top of their normal responsibilities. And they have to do it with fewer staff.

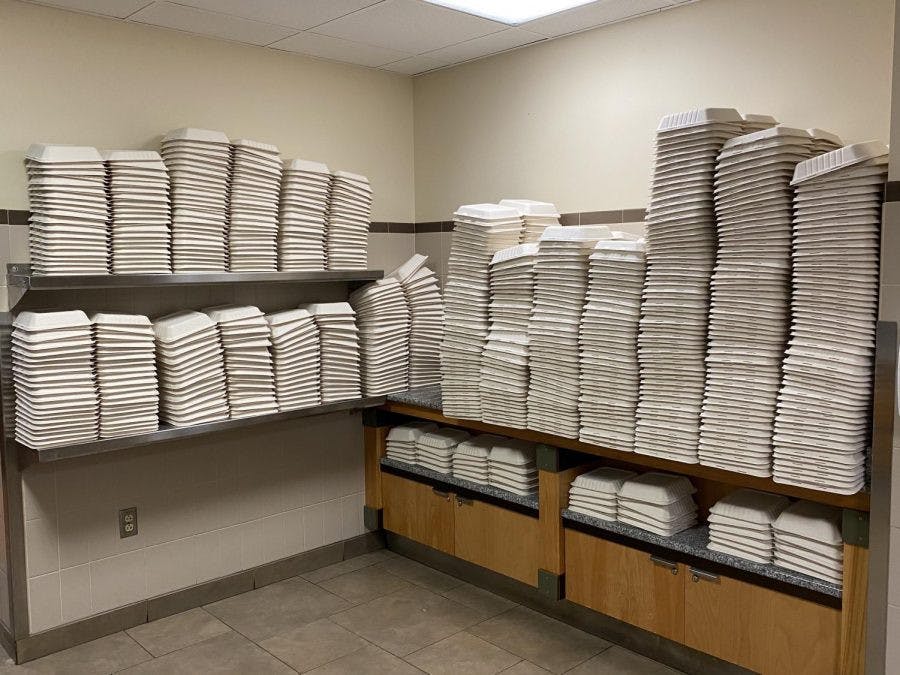

During meal times, staffers are frantically filling and stacking to-go containers in preparation for the dinner rush. At my station, we tried to have more than 50 containers ready to go at all times. The day I worked was the first day of Phase Two, and the rush never really arrived, probably because everyone was enjoying their newfound freedom. But most days during Phase One, especially Mondays and Tuesdays when the Grille was closed, students came crashing in like a tidal wave at 6 p.m., overwhelming the staff and quickly wiping out the stock-piles of meals no matter how diligently staff prepared in advance. The number of meals served frequently reached 800 to 900 during Phase One, according to the staff member.

When three staff work the line, one has to serve pasta, another the meat course, and the third the vegetarian option. When something runs out, they have to interrupt the serving to switch out trays of food, causing the entire operation to fall behind.

One of the most onerous tasks is stacking the to-go containers. They all have to be brought up from downstairs, unpacked, and neatly stacked in a little alcove at the serving stations, a task that can easily take two people over an hour and must be done multiple times a day. If they run out of stacked containers during serving times, one of the three employees has to leave the line, interrupt their work, and get more, throwing the whole operation off balance.

The dining halls have also had problems with food supply, which has been irregular and temperamental. They have frequently had to make last minute changes to the menu and have sometimes run out of food midway through the meal, wreaking havoc on the existing workflow as someone has to frantically whip something up.

With so few staff, the little tasks that make work easier and more efficient — like separating and cross-stacking serving dishes for easy access — have to fall by the wayside in favor of the immediate need to serve students. Instead, staff have to confront those issues as they pop up. Without those crucial time-saving preparations, the work and stress only continue to build, according to William Anderson ’20.5, who has worked as a kitchen staff helper since Oct. 2017.

Each shift thus turns into a frantic race to keep up with the deluge of students. When things get busy, even the short amount of time it takes to leave the swelteringly hot line, take off your gloves, gulp down a few sips of water, and replace your mask and gloves feels like an unaffordable luxury. Each time I pierced the crispy breaded layer of the fried chicken with my tongs to serve hungry students, I was taunted by the scents of rich, buttery deliciousness. With none to spare, my grumbling stomach was left to complain to itself.

Just one shift takes a “physical toll” on your body, according to Betsy Oullette, a catering employee who has been reassigned to work in dining twice a week. This exhaustion only builds for staff who have been forced to work more days and longer hours. Though dining staff’s responsibilities increased, the college’s hiring freeze prevented Dining from hiring new workers to replace those who did not return to work this year due to fears of contracting Covid-19. During Phase One, one staff member worked 21 out of 23 days. Most staff regularly worked upward of 50 hours a week, according to the anonymous staff member.

After returning to my dorm at the end of my shift, absolutely spent, I realized that I had forgotten my camera in the locker room. I rushed back at 9:30 p.m., expecting everyone to be gone, only to find one employee still working. His shift began at 9 a.m. — he had worked more than 12 hours that day.

Things have been improving now in Phase Two. During evening meals, servery staff have been helping serve at the line, freeing dining staff to resume their normal responsibilities. Meal counts are also down slightly as students can now go into town to eat or buy groceries.

Still, even amid all the stress, new Covid-19 guidelines and short-staffedness, the dining hall was cheerful and emanated a welcoming comradery.

“You really, really, really only get through a busy or tough shift with humor and we have that in abundance there,” Anderson said.

Anderson joked with his friend on staff as they planned to go for a hike on their day off, and showed off to everyone the knife the friend had spontaneously given him. Oullette asked one of the new first year student workers about her classes as they served vegetarian meals. Everyone traded tips on the most efficient ways to fill meal boxes, and Oullette or others would often intervene to help me manage my stack of containers. Calls of “behind you with a hot plate!” interrupted the choreographed rhythm and concentration of filling boxes. Anderson described the kitchen dynamic as that of a family, with younger staff joking around like siblings and supervising staff functioning as alternatingly stern and understanding parents, managing the chaos.

The occasional “thank you” from passing students felt like a jolt of energy, a small motivation to hurry my dragging feet. As the shift wore on and I grew more and more tired, these small motivators made all the difference. Anderson says that he appreciates when students treat him and the staff like actual people, thanking them or briefly conversing with them as they pass along in line. Behind the counter, it's easy to feel invisible. Dressed in a dining hall uniform, with a comically big blue chef’s hat covering my hair and a mask covering my face, I made direct eye contact with a number of friends who completely failed to recognize me, only to startle in surprise when I said hello. Many students ignored me completely.

The best moments are when students compliment food from previous meals, according to Anderson. The staff work hard to prepare meals for students and take pride in their work, though it often goes unrecognized. In those rare moments where someone does take the time to compliment their hard work, it makes all the difference.

Sophia McDermott-Hughes ’23.5 (they/them) is an editor at large.

They previously served as a news editor and senior news writer.

McDermott-Hughes is a joint Arabic and anthropology and Arabic major.

Over the summer, they worked as a general assignment reporter at Morocco World News, the main English-language paper in Morocco.

In the summer of 2021 they reported for statewide digital newspaper VTDigger, focusing on issues relating to migrant workers and immigration.

In 2018 and 2019, McDermott-Hughes worked as a reporter on the Since Parkland Project, a partnership with the Trace and the Miami Herald, which chronicled the lives of the more than 1,200 children killed by gun violence in the United States in the year since the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shooting in Florida.