Recently, I’ve taken to getting lost. I’ll pull on my sneakers and just run — no map, no plan, no time limit. The first time I did this, it was a mistake; my excitement to step off campus as soon as Phase Two began left me in the middle of a faint path somewhere slightly off of the TAM, a good couple of miles away from where I had intended to be. After dozens more miles, one cow stampede and several additional wrong turns, I’m still at it, wandering by foot on trails all over Middlebury.

I never thought that I would be someone who enjoyed getting lost. I’m the type of person who uses Google Maps every single time I drive just to make sure I arrive perfectly on time. Add in a healthy (but warranted!) concern about wildlife and an abnormally poor sense of direction, and you might think that wandering in the woods doesn’t really seem like it would be that great of an idea for me.

The truth is, most of the time, I do like knowing where I am, what I’m doing and where I have to be. I’m not unique in this: from the time we are in elementary school, we are taught to plan. And most of us, by now, are really good at it. At a school like Midd, this is unsurprising. We plan a lot, choosing our classes around distribution requirements and majors — ones that will be challenging enough to look good on a resume but not too challenging that they hurt our GPAs. We plan internships and interviews and grad school applications.

But what does all this planning get us?

Even as a liberal arts college that aims to create “a transformative learning experience” and “foster inquiry, equity and agency,” Middlebury isn’t immune to over-rationalization because it exists in a world where higher education isn’t defined by the intrinsic value of learning. Instead, a college education is seen as a means to an end. Despite establishing admirable, abstract goals that seem to emphasize a holistic student experience, one look at the admissions website reveals that the perceived value of a Middlebury education revolves around employment or postgraduate education, neither of which are necessarily connected to personal fulfillment outside of the professional sphere.

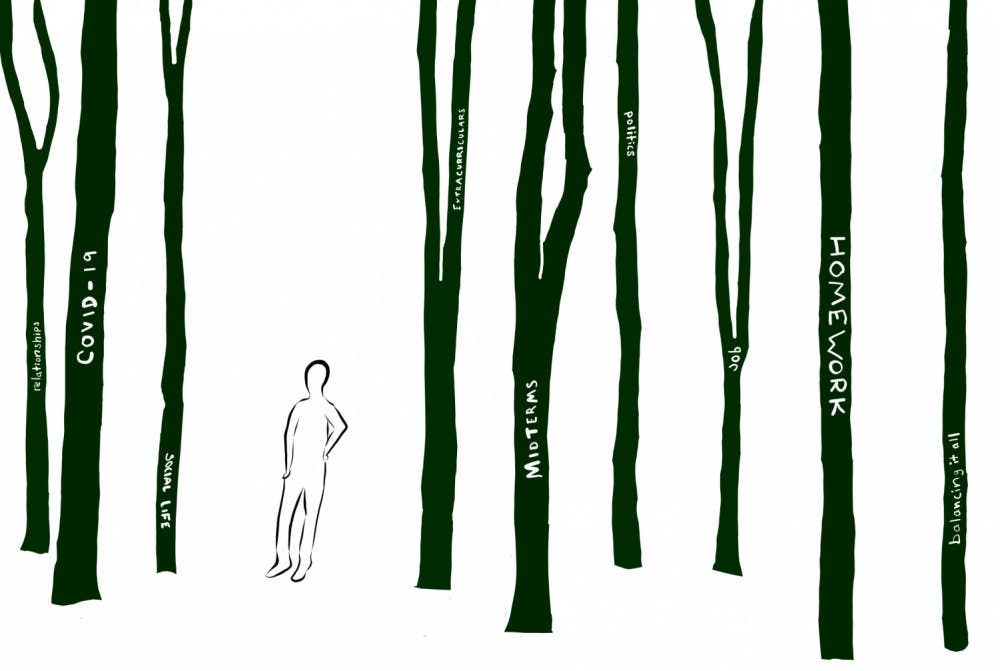

Somewhere along the way, we are taught that establishing concrete goals for our future — with their requisite strict set of steps to get there — will help us reach that all-too-nebulous idea of “success.” But success is often relative, and the completion of one step just leads to the next, leaving us stuck in a mindset of never-ending ascension. With our futures supposedly on the line, there’s not much room for risk-taking, experimentation or creativity. Pursuing interests that may be personally fulfilling but conflict with our concrete ideas of success is therefore discouraged.

There has been a lot of talk recently about being more intentional. New Covid-19 guidelines have transformed the way we interact, allowing the intentionality that drives our academic pursuits to seep into our relationships. Although it can be useful to put more thought into how we connect, as Maria Kaouris and Ben Beese have suggested in their recent op-eds, we need to be careful of letting meticulous planning dictate our personal lives. In a small environment like Midd, room occupancy limits and scrupulous planning of social events seem to lead to the maintenance of already-established connections rather than the development of new ones. Because we no longer have the same outlets for spontaneous socialization, we need to discover new ways of injecting the novelty of random interactions into our everyday experiences.

And so, to counteract all of the structure that is all-too-quickly taking over my life, I get lost. In his WSJ article, “Take a hike and get lost,” Colin Fleming explains the tension between the need for freedom and desire for the comforts of our many plans, writing, “We fight for so much control in our lives, and we feel frightfully unmoored without it.” It’s scary to go headlong into something without knowing how it will turn out. But that fighting is exhausting and, oftentimes, it prevents us from appreciating what is already around us.

It took being quarantined to this campus for me to realize that in my three years here, I have never really stepped outside of it: outside of all the structures and requirements that are simultaneously comforting and confining. New guidelines may require more intention, but more than ever, we need to make time for the unintentional, for the happy accidents, for the sidetracks, for the pointless wanderings.

I run to get away from it all — the list of assignments, the connections I should be making, the structured practices. I run because there is more to life than just a line of checkmarks and an ever-accumulating list of achievements. And a lot of the time, I end up in the middle of the woods with absolutely no idea where I am, but I’ve found that getting lost makes for a better run anyway.

On getting lost in it all

Comments