Last July, the United States celebrated the 30th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA), the civil rights law that sought to end disability-based discrimination and guarantee the right to accessibility in public spaces. Though the ADA was a monumental step forward towards disability justice, it falls woefully short of upholding the rights it promises. The road to true accessibility remains long and uncertain for those of us who have no choice but to continue to traverse it, even in a tight-knit college community that prides itself on its commitment to social justice.

As a Middlebury junior who is both physically disabled and learning-disabled, I have spent the last three years navigating my way through the entrenched inaccessibility of the spaces in which I live and learn. From struggling up the stairs of buildings without elevators to get to office hours to spending hours trying to justify my academic accommodations to professors, administrators and even the Disability Resource Center itself, I have experienced firsthand many of the ways in which life at Middlebury can make disabled students feel as though we are an afterthought — to be included only when it is convenient.

Though they may appear broad and unrelated at first, all of these accessibility issues stem from the same root problem: the ways in which we view accessibility and accommodation themselves.

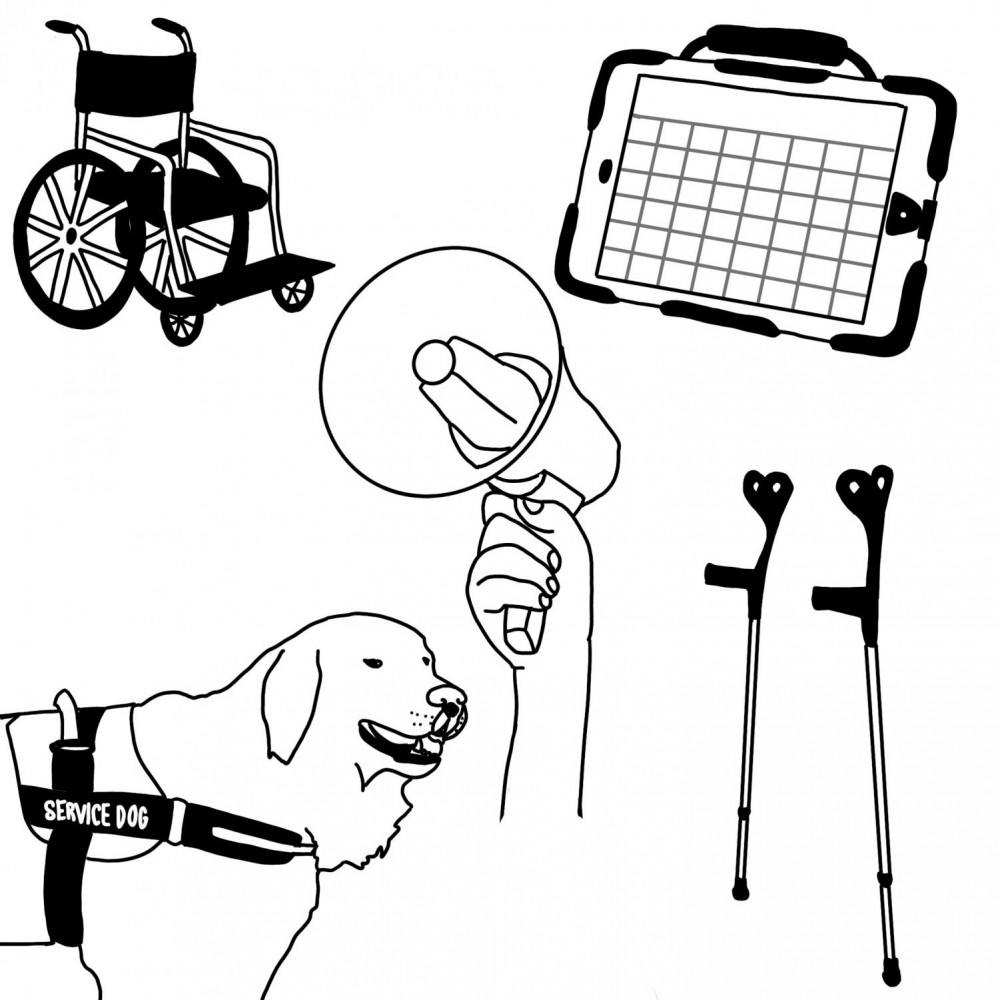

When we think of accommodations or accessibility tools, we often think of things like wheelchairs, service dogs and extended time on exams. But what if I told you that we all use accessibility tools and accommodations every single day, regardless of our disability status?

I’d like you to think about the last time you wore a jacket. A jacket keeps your body warm when your surroundings are too cold for your body to do that on its own. This is, of course, no inherent fault of your body; rather, the cold temperature and your body’s natural need for warmth means that for a time, your body and the environment are incompatible. A jacket serves as a bridge towards compatibility — in other words, an accessibility tool or accommodation. The same goes for cars, glasses, computers and countless other essential tools we use on a daily basis.

You may struggle to think of these ordinary, everyday examples as "accommodations" because the word "accommodation" implies a favor — like someone or something is going out of their way to help you. But access to warm clothing is a basic human right, not a gift, so we don't usually think of a jacket as an accommodation. Why is it, then, that the only things we consider “accommodations” are accessibility tools that appear to only be needed by disabled individuals?

The perception of accessibility as a favor that one can choose to extend to others is at the core of many of the inaccessibility issues we face at Middlebury. Some of the academic accommodations I rely on the most, like occasional extensions on assignments, are considered optional; a professor is permitted to choose whether or not they personally feel such an accessibility tool is reasonable enough to implement.

I have spent hours listening to professors complain to me about how my accessibility needs will make their workflow more challenging or ruin their weekend. However, I can count on one hand the number of times I have heard it acknowledged that significant adaptations to the status quo are only necessary because the systems in place at the course, departmental, institutional and societal levels were not designed with disabled students in mind, thus hindering our ability to succeed.

Placing the blame on the student in these instances is not only harmful to a student’s well-being but also perpetuates the idea of accessibility as a favor that is being graciously granted to someone who should be thankful to receive any consideration at all. Furthermore, it excuses significant inaccessibility if eradicating it would take more than a minor effort by those who already have access to the spaces, learning environments and fields of study that so many of us are still actively excluded from; some of my disabled friends have even been told that perhaps Middlebury just isn’t the place for them.

But who, then, is Middlebury a place for? Who gets to belong here?

I’ll ask you to consider this: if someone's request for accommodation would cause you to change so much about the way you run your workplace, course, event or institution that it seems unreasonable, perhaps it isn't the accommodation itself but rather the fundamental design of your workplace, course, event or institution that is unreasonably inaccessible.

And though addressing those underlying barriers may seem like an extreme shift away from the comfort of the status quo, that is what it will take to dismantle a system of exclusion that digs its roots ever deeper the longer we continue to uphold it.

How can we move forward? As an institution, we need to immediately rectify the physical inaccessibility of many of our campus buildings; a quick glance at the pastel-green campus map we distribute to new students demonstrates that a significant portion of our buildings lack even a single accessible entrance, much less an accessible interior. We must also commit to offering remote opportunities for engagement even after the pandemic is over; recordings of live lectures and Zoom office hours should remain available for students who need them.

More broadly, professors and administrators must begin thinking critically about how to eliminate the underlying inaccessibility within individual courses, departments and campus life. They must also be given the training and resources to address these pervasive problems effectively and sustainably. As students, we can express the urgent necessity of such accessibility measures in our conversations with faculty, staff and — above all — the administration, demanding that significant funds be allocated to address systemic inaccessibility at Middlebury.

Perhaps we have long brushed aside Middlebury’s inaccessibility as an inherent, dismissible consequence of its historical charm and academically rigorous character. Perhaps we have never found the right time to address it sustainably, settling instead for short-term solutions and band-aid fixes. But the myth of a “right time” is just that — an illusion; it’s high-time we start taking accessibility seriously, and we need to do so now.

Isabel Linhares is a member of the class of 2022.

Accessibility isn’t optional, even when it’s inconvenient

Comments