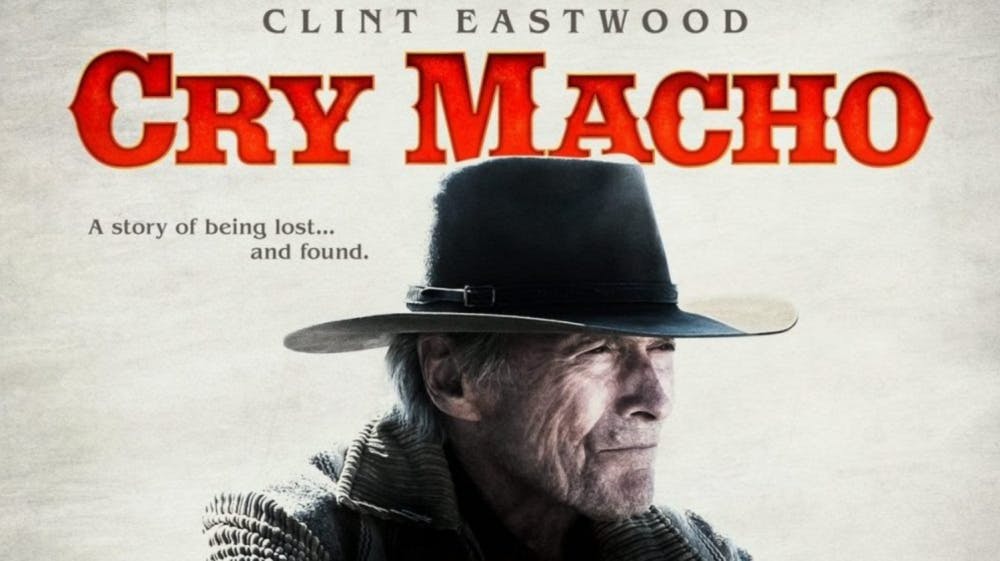

“Cry Macho” opens on a truck driving down a country road. Inside, we see squinted eyes under a beaten cowboy hat glance into the rearview mirror. The truck pulls to a stop, and the camera drops to the ground to watch as two leather boots step out onto the pavement. It then cuts to the driver-side door shutting, and then we see him: Clint Eastwood, the sun at his back, still the archetypical American Western hero at 91 years of age that he was 60 years ago.

“Cry Macho” opens on a truck driving down a country road. Inside, we see squinted eyes under a beaten cowboy hat glance into the rearview mirror. The truck pulls to a stop, and the camera drops to the ground to watch as two leather boots step out onto the pavement. It then cuts to the driver-side door shutting, and then we see him: Clint Eastwood, the sun at his back, still the archetypical American Western hero at 91 years of age that he was 60 years ago.

It is clear in just the first two minutes of the film that director and star Clint Eastwood understands the baggage that he carries with him into this role. Making his first appearance in a Western since his 1993 Best Picture Winner “Unforgiven,” he knows that his donning of a cowboy hat is all that audiences need to feel the years of rich cinematic history packed into this film. Eastwood plays with this connection between the audience and the icon, as silhouettes of his character Mike Milo against the sun setting over the desert erase his age. He could just as easily be the Man with No Name from Sergio Leone’s “The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly.” Herein lies one of the joys of “Cry Macho.” Though it is a film held back by a screenplay that is uneven in its storytelling and blunt in its dialogue, it is redeemed by an endearing Eastwood performance, the beautiful desert scenery and some of the sweetest moments in the director’s filmography.

Mike Milo is a former rodeo star living out the last years of his life alone following the death of his wife and son in a car accident. In return for the financial support he lent Mike following the loss of his family, Mike’s boss Howard (Dwight Yoakam) comes to him asking for a favor: travel from Texas to Mexico to retrieve Howard’s son from his affluent, alcoholic mother. Mike accepts, and after finding the boy in Mexico City, sets off on the road back to Texas. He is all too quickly pursued by Mexican federal police and private enforcers, both sent by the mother to take back her son.

Despite what its plot may imply, “Cry Macho” is anything but a thriller. Much like its white-haired star, the film is gentle, methodical and earnest, which works brilliantly in some regards but fails in others. This earnestness shows up as a problem in the dialogue, much of the issue stemming from Eduardo Minett’s Rafo. The character’s lines are devoid of any subtlety and delivered with binary emotions. Rafo is either one hundred percent happy or one hundred percent sad, never a realistic, complex mix. His spoken words — he at one point says to Mike, “I don’t trust you anymore” — are borderline cringeworthy.

It is a great relief that Eastwood is not tainted by this problem. His portrayal of Mike is natural, filled with moments of sly humor, wisdom and a warm sensitivity that is miles away from the steely intensity of his William Munny in “Unforgiven.” Mike chokes up, recalling his deceased family, and as he lies down in the dark, his hat pulled down over his eyes, all we can see is a single tear rolling down his cheek. These quiet, human moments are what make “Cry Macho” tick, and they are never more bountiful than when Mike and Rafo spend time with a widow named Marta (Natalia Traven) and her family.

Mostly set in the restaurant Marta runs in a small Mexican town, this extended sequence finds the film forgetting about its plot momentarily to settle down and simply breathe with the characters. They eat meals together, they dance, they tend to sick animals and they laugh. It plays like a dream, and the rest of the narrative fades into the periphery. Not only is watching Mike and Rafo form a familial bond with Marta and her granddaughters the highlight of the film, but it is also possibly the most heartwarming sequence that Eastwood has ever shot.

The flimsiness of the screenplay doesn’t allow the film to maintain this emotional power once Mike and Rafo are forced to leave their new home behind. What is supposed to be the final confrontation between Mike and one of the men hunting him lasts no more than two minutes and is extremely anticlimactic. Then, in the most disappointing part of the film, the plot runs its course to reach an expected conclusion without the characters pushing the drama into new territory. Is this an intentional effort by screenwriter Nick Schenk to subvert audience expectations by ending the film and giving them an ending that is almost too obvious? Or is it simply a boring ending?

Thinking back, it doesn’t matter either way. The film was genuinely moving, and audiences got to see one of their favorite Hollywood stars step gracefully back into the role that he defined. You can’t ask for anything more than that.

Jack Torpey '24 (he/him) is an Arts and Culture Editor. He writes film reviews for the Reel Critic column.

Jack is studying English with a minor in Film and Media Culture. Outside The Campus, he works as a peer writing tutor at the Writing Center and is a member of the Middlebury Consulting Group.