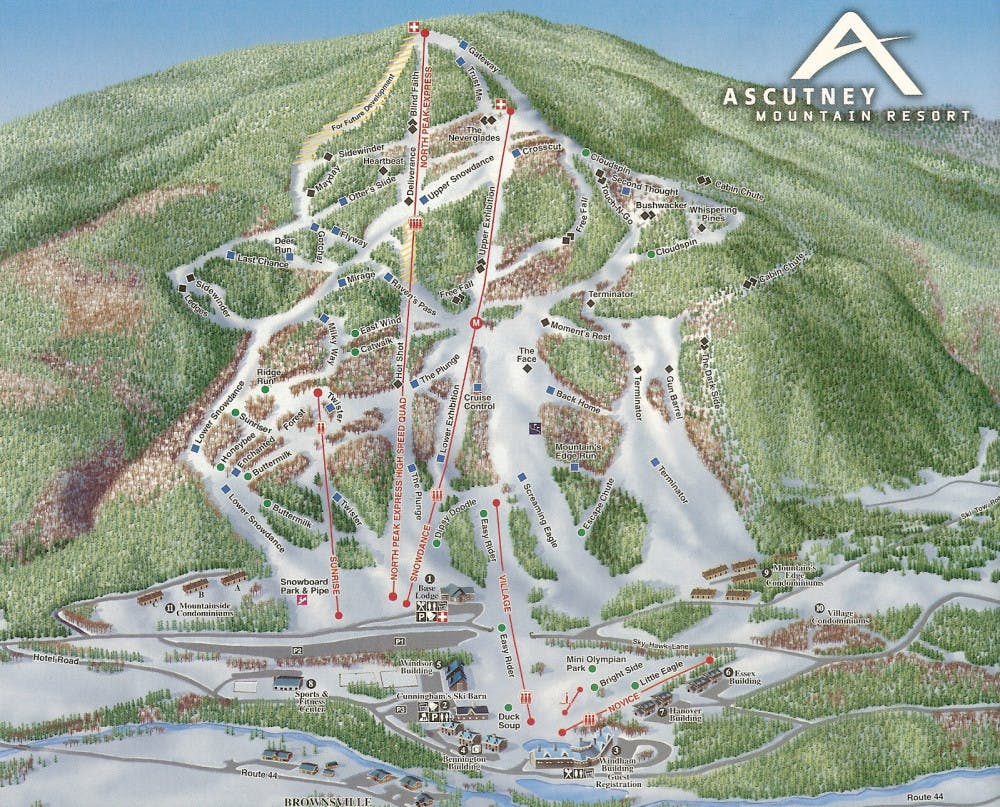

Ascutney Mountain Resort, located in Brownsville, Vt. is poised to enter its third consecutive winter of inactivity. The mountain resort operated 57 trails and six lifts across 200 square miles and 1800 vertical feet of skiable terrain until 2010 when it filed bankruptcy. Ascutney is the most recent addition to a growing list of closed ski areas across the state, and Vermonters are worried about the future of the sport — the Vermont ski industry peaked in 1966 and has been steadily declining ever since.

At its height, Vermont had a whopping 81 ski areas in service. Over the years, the number open in a single season has risen and fallen with fluctuating economic and weather conditions, with today less than 20 ski resorts and a select few Snow Bowls still running in Vermont. There are now 113 documented “lost ski areas” in Vermont, according to the New England Lost Ski Area Project (NELSAP).

Tropical temperatures last March cut the ski season short by nearly three weeks. Vermont ski areas suffered not only from a shorter season, but also from persistently poor conditions throughout the winter. Not a single large snowstorm hit the northeast last year, forcing ski areas to bring out the snow blowers or risk bankruptcy.

Mad River Glen in nearby Fayston, Vt. — a mountain committed to resisting modern snowmaking technology — suffered last year as a result of the limited snow accumulation. The ski area uses snow blowers and groomers only sparingly — even last year Mad River resisted the urge to expand snowmaking technology past the 15 percent of trails currently covered by snow guns. Open a mere 71 days last year, the mountain lost money. In order for the enterprise to be profitable, it would need to operate for at least 100 days.

The future of Mad River, and countless other Vermont ski areas, is in jeopardy if current climatic trends continue. Ski towns — dependent on the influx of skiers for business — are struggling as much as the mountains themselves. The lack of skiers in the Brownsville area due to the closure of Ascutney mountain resort in the last two winters has already caused several restaurants in Brownsville to close.

Vermonters remain convinced that the ski industry will remain a fixture in the Vermont landscape for economic and cultural reasons.

Despite the poor snow accumulation last winter, Vermont ski resorts suffered relatively less than ski resorts in other parts of the country; nationwide, resort visits were down 16 percent from the previous season while number of skiers hitting Vermont slopes in 2011-2012 dropped by just 11 percent.

“Skiing is an important part of our heritage and economy,” said Parker Riehle, president of the Vermont Ski Association.

“Skiing is more than just an iconic product, like maple syrup or cheese,” said Vermont native Amanda Kaminsky ’13. “It is an experience that epitomizes the value Vermonters place on the outdoors.”

The experience of many native Vermonters working in the ski industry, however, makes this optimism seem anachronistic. Okemo Ski Instructor Ellen Bevier ’16, of Rutland, Vt. knows at least a dozen Vermonters who have been laid off from ski areas since the recession hit. Snow sports are more than just a pastime for people like Bevier, whose father worked at a ski mountain for the entirety of her childhood.

Governor Peter Shumlin shares the optimistic attitude of many Vermonters despite recent trends. He remains convinced that the fact Mad River and countless other ski areas survived after such a rough year is a testament to the hardiness of Vermont’s ski industry.

“Our future looks bright,” said Shumlin in a televised speech last March at the Vermont Ski and Snowboard Museum. “Our mountains continue to expand and become four season resorts. This grows jobs and economic opportunities for all of us.”

Long before the recession hit, small ski areas were already being lost due to trends toward modernization. Finding $40,000 for a new T-bar back in the day was one thing, but finding $250,000 for a new chair lift is often beyond the budget of small ski areas.

Fewer and fewer people, especially out-of-staters, were willing to go to tiny five-run ski areas without snow guns and high-speed chairs when bigger mountains — Okemo, Mount Snow, Stratton, Bromley and Killington, the five-mountain, five-lodge “Beast of the East” — were just around the corner.

“I don’t think I’ve experienced a single winter here without hearing doubts over whether Magic Mountain would survive another season,” said Vermont native Cheyanne Pugliese ’16, who prefers smaller mountains like Magic Mountain to behemoths like Killington.

Increasing costs of operation and rising skier expectations have forced small mom-and-pop businesses to adapt or perish.

Magic Mountain in Londonderry has managed to remain open through creative strategizing — they rely on community volunteers and conservative spending practices. Both Magic Mountain and Mad River Glen have turned to co-opting strategies to generate enough revenue to remain solvent.

In coming years, the main challenge for ski areas will be convincing skiers to hit the slopes when they don’t see any snow outside their windows. Ski areas are using online resources like Facebook and email alert systems to advertise snow on the slopes. Mountains are also asking skiers to adjust their expectations in the event of another winter like the 2011-12 season.

Vermont Ski Industry Faces an Uncertain Future

Comments