In the wake of a high-profile student protest and amid a growing university movement to combat climate change, Middlebury College announced in early December that it would initiate steps to address the feasibility of divesting its endowment from the fossil fuel industry.

In a campus-wide email, College President Ronald Liebowitz expressed his willingness to “engage the community on an issue of great interest and import to the College and its many constituents”—a commitment to expand dialogue on concerns previously only discussed seriously in activist forums. He explained that Middlebury would host a series of panels on divestment with representatives from the College’s endowment management firm, Scholar-in-Residence Bill McKibben, and veteran investors. “A look at divestment,” he continued, “must include the consequences, both pro and con, of such a direction, including how likely it will be to achieve the hoped-for results and what the implications might be for the College, for faculty, staff, and individual students.”

In an unusual and impressive demonstration of transparency regarding the College’s finances, Liebowitz also disclosed the percentage of the institution’s $900 million endowment currently invested in fossil fuel companies: roughly 3.6% or $32 million. The statement provided a degree of openness that many say has been missing since 2005 when the College began outsourcing the investment of its endowment to Investure, LLC, an investment management company with an aggregate portfolio of approximately $9.1 billion.

Liebowitz’s announcement was met with enthusiasm from McKibben, the founder of grassroots sustainability organization 350.org and chief spokesman for the organization’s Do The Math tour, a national campaign encouraging colleges, churches and pension funds to divest their endowments from the world’s top 200 fossil fuel companies.

“President Liebowitz used just the right tone and took precisely the right step,” said McKibben in statement released by 350.org. “It won't be easy to divest, but I have no doubt that Middlebury—home of the first environmental studies department in the nation—will do the right thing in the right way.”

On the rural Vermont campus, some students were more tempered in their reaction to the statement. Why wasn’t the College considering more definitive steps, committing to fossil fuel divestment like Unity College in Maine, or pledging to invest in sustainable and socially responsible companies, like Hampshire College in Massachusetts?

“We want to see change happen faster,” said Sam Koplinka-Loehr, a senior environmental justice major. “Panels and discussions are not new,” he explained, “they have been happening since before I arrived on campus.” Koplinka-Loehr was one of five students disciplined by the college for the dissemination of a fake press release in November—a prank designed to raise awareness about divestment and encourage the college to take action.

Other students wondered how the College’s practice of outsourcing its endowment management to Investure—which pools Middlebury’s funds with the endowments of twelve other institutions or foundations—might impact the viability of divestment. The President’s email included a disclaimer noting that the financial information provided was not based on a comprehensive review of Middlebury’s holdings, but rather “the underlying long positions of the Investure Funds of which Investure has actual knowledge from third-party managers.” While this model permits greater efficiency and economies of scale, the many steps of remove limit transparency and could complicate the divestment process.

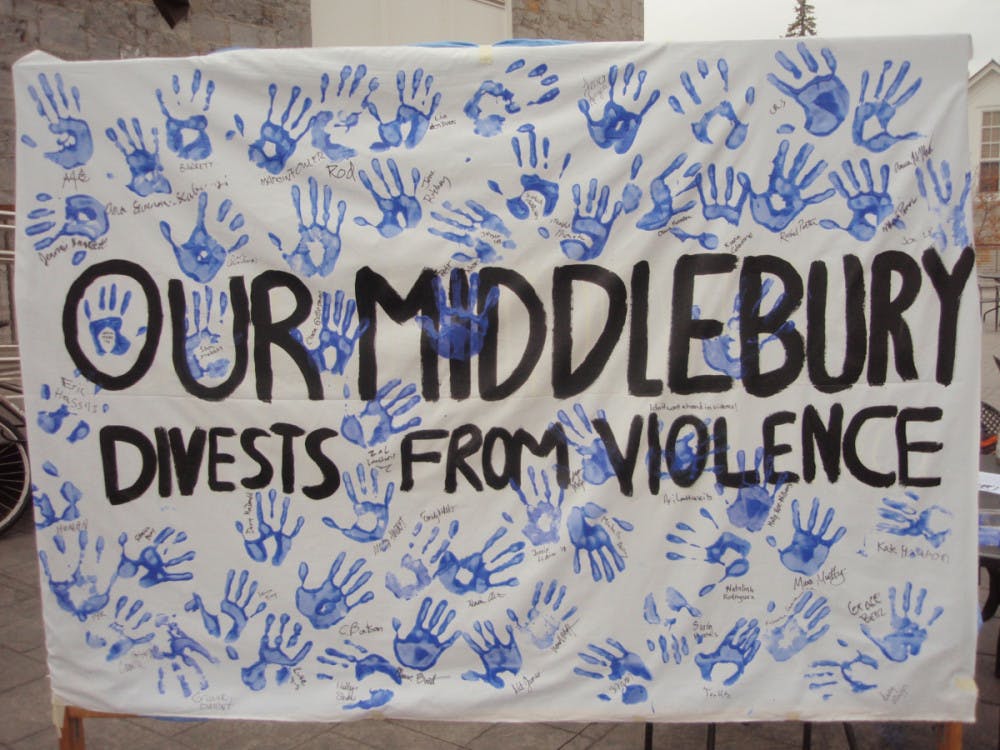

Members of the student group Divest for Our Future, however, argue that Investure’s co-mingled endowment structure opens up potential for collaboration. They have been in contact with similar student groups at Investure-managed schools such as Smith College, Barnard College and Trinity College in an effort to coordinate initiatives, hoping that acting in unison might encourage Investure to alter its investment policies across the board.

This type of joint effort has a history of success. In 2010, Middlebury students teamed up with representatives from Dickinson College and the Rockefeller Brothers Fund—both of which have endowments managed by Investure—to establish the Sustainable Investments Initiative, an Investure-managed portfolio dedicated to environmentally responsible investment. With $4 million from Middlebury, $1 million from Dickinson, and $70 million from the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, the portfolio has yielded high returns, says Ben Chute, co-leader of the Socially Responsible Investment Club at Middlebury.

Outside of the logistical debate on feasibility, divestment as an effective strategy to strike a blow at the fossil fuel industry has faced criticism. Nation contributing editor Christian Parenti has questioned the effectiveness of using coordinated divestment as a tool to affect the bottom line of fossil fuel companies, suggesting that if universities were to sell their shares, someone else would likely scoop them up.

Jon Isham, an economics professor and director of Middlebury’s environmental studies program, thinks that while the direct effects of divestment on fossil fuel stock prices may be negligible, the move—if widely adopted—could significantly damage the industry and encourage investment in sustainable energy. “It’s wrong to say that divestment in and of itself is going to effect change solely based on the implications for stock prices,” said Isham. “But it might still make fossil fuel companies worry—it could mean that stock is viewed as something nobody should hold, which happened in tobacco. Divestment is an attempt to give the industry a black eye.”

The divestment movement “is something college students can latch on to,” explains Isham. “They understand their campus, they’re on their campus, and they are very keen on making a difference in the world, not only around climate change, but also around poverty and human rights. This is a way they can make change on campus.”

Indeed, Middlebury students have pushed for the upcoming panel discussions to incorporate representatives from student organizations such as Divest for Our Future and the Socially Responsible Investment Club. “If there is true intent to listen to student voices, the administration should provide avenues for students to engage in these issues,” said Koplinka-Loehr. “We need the opportunity to engage in critical dialogue on equal footing with the administration if we are to be successful.”

KELSEY COLLINS contributed to this report. The article was originally posted to the Extra Credit blog in the Nation.