Past a locked glass door and a chair that belonged to Robert Frost is Special Collections within the Davis Family Library, the space in the Library’s basement that primarily comprises the books you will not find shelved in the stacks.

“It’s both a collection of materials that are either very rare, unique, expensive or fragile, so there are a few different varieties,” Director of Collections, Archives, and Digital Scholarship Rebekah Irwin said. “Generally, the oldest books in the collection are here, and some special collections are set aside.” Within Special Collections are the collections of books such as the Abernathy Collection – a trove of manuscripts and rare books from great American authors of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Priceless books such as Henry David Thoreau’s personal copy of “Walden” are kept in Special Collections.

“So that’s a very valuable and, of course, irreplaceable item which is kept in a safe,” said Assistant Curator of Special Collections and Archives Danielle Rougeau. Even if they are not books, items of significance to the literary world are also housed in the collections.

“Thoreau’s father and Thoreau for part of his young adulthood were pencil-makers. So we have Thoreau pencils and a box that the pencils came in,” Irwin said. “I don’t know how many students know that the chair that sits in the front is Robert Frost’s chair and his moth-eaten sweater that sits on top of it, and his radio from the Frost cabin in Ripton.”

Other collections are more unconventional, such as the Helen Flanders archive, made up of recordings collected by the eponymous researcher and folklorist who traveled across Vermont during the mid-1900s to record folk songs.

“We have 250 or so of her Edison wax cylinders that she used to record as well as thousands of records and early reel-to-reel tapes that she made,” Irwin said. “It is a collection wthat is very popular among folklorists, musicians and researchers who are interested in how folk music traveled from Europe to America.”

Rare Books and Manuscripts holds the books that, for the sake of preservation, have to be kept in certain conditions and not tossed in a backpack and walked around campus. These books are instead used in the Special Collections reading room.

“The Manuscripts part of [Rare Books and Manuscripts] is unique manuscripts, usually from authors,” Watson said. These manuscripts include drafts of books before they are published, as well as letters and research papers.

Oftentimes, these manuscripts reveal information about an author.

“We have those collections, so if someone is interested in the process an artist or writer goes through, we have those raw materials,” Irwin said. “And that is something you can study to learn about the person or the process of writing.” Rare books also includes a growing collection of Civil War letters.

A recent gift came from the spouse of an alumnus who was a niece of Ernest Hemingway and gave many of personal diaries and letters from the family.

“So if you’re really into Hemingway, you’d be thrilled the collection here,” Watson said. “It’s the kind of thing that we would have researchers coming nationally or internationally to do research on.”

The College Archives, a collection of any items and publications produced by people associated with the College, is an important part of Special Collections’ mission.

“By the nature of being as old a school as we are, we have an amazing range of materials in the collection dating back to 1800 and before,” Irwin said. “It reflects what is happening in society by the activities happening here and we have the benefit of over 200 years of collecting.”

While the priceless items in the collection are of use to researchers, the Special Collections staff primarily serves students as well as administrators.

“When the College does new things, they also like to look backwards,” Irwin said. Especially when considering changes to departments, such as the split of History of Art and Architecture and the Fine Arts department in 1997, according to Irwin, administrators like to examine the precedent that can be viewed in the Archives.

“We’re supplying them usually with research information that they need to produce flyers and brochures but they’re also asking us for images often,” Rougeau said.

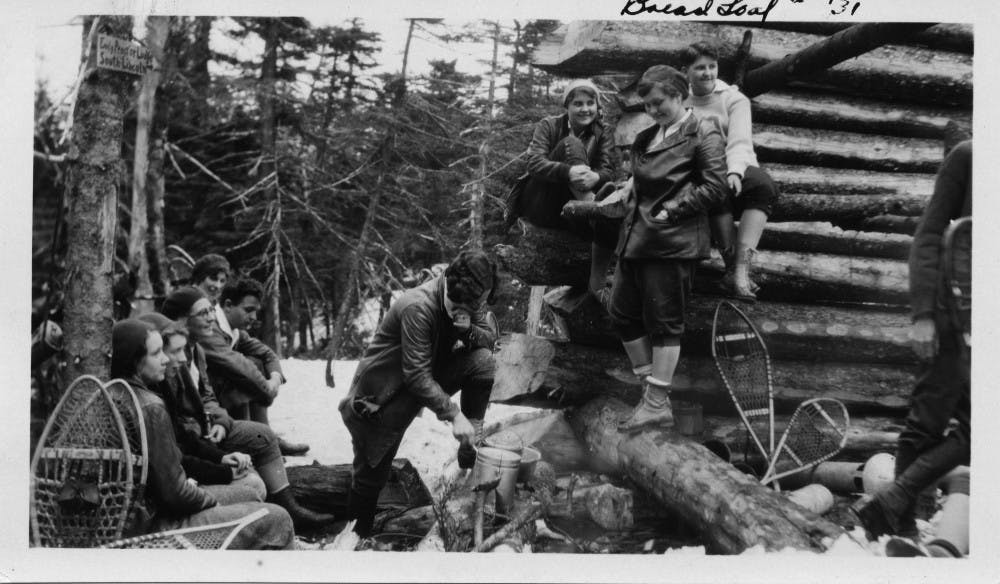

According to her colleagues, Rougeau’s ability to recognize and name the faces in the photographs of the Archives is unrivaled.

“She’ll look at a photo of a dinner in 1905 or 1911 of the alumni group in New York City, and she names 10 people in the photograph,” Watson said. Rougeau speculates that working with the materials since 1994 is why her memory of the people in Middlebury’s past is so keen.

“I feel like I have a responsibility to try to document this so that the names are there and it’s available,” Rougeau said.

At the end of the day, however, Special Collections can only delay the inevitable.

“All things made of paper are made of organic materials, and all organic materials slowly degrade whether it’s our bodies or a tree or a piece of paper and the point of preservation is to slow that down as much as you possibly can if you want to keep it in the future,” Watson said. This reality has led to a digitization effort, with photographs, manuscripts, and materials from the Archives are being scanned in order to preserve them. Nevertheless, the ability to digitize has its downsides.

“We have photos and scrapbooks and letters and diaries of students of Middlebury College through the 1900s and into the 20th century but the last time one of you or your classmates wrote a letter to a friend, kept a journal on paper or took a photo and made a print of it, it’s been a long time,” Irwin said.

The Internet and digital media are hampering the Archives’ ability to tell the story of events that happened on campus.

“A student can come to our archives and can study how women at Middlebury organized themselves around women’s suffrage or abolition or any big political movement because we have documents that tell that story,” Irwin said. “But if a student 10 years from now wants to understand what was happening around climate change on campus or divestment, so much of that was happening not on paper but on social media and digital cameras and cell phones and on blogs. We need to make sure that we can tell that story and that a student doing a history thesis a decade from now is able to see those materials.”

Preserving the Past for the Sake of Midd's Future

Comments