Emma ’14 first snorted Adderall halfway through sophomore year.

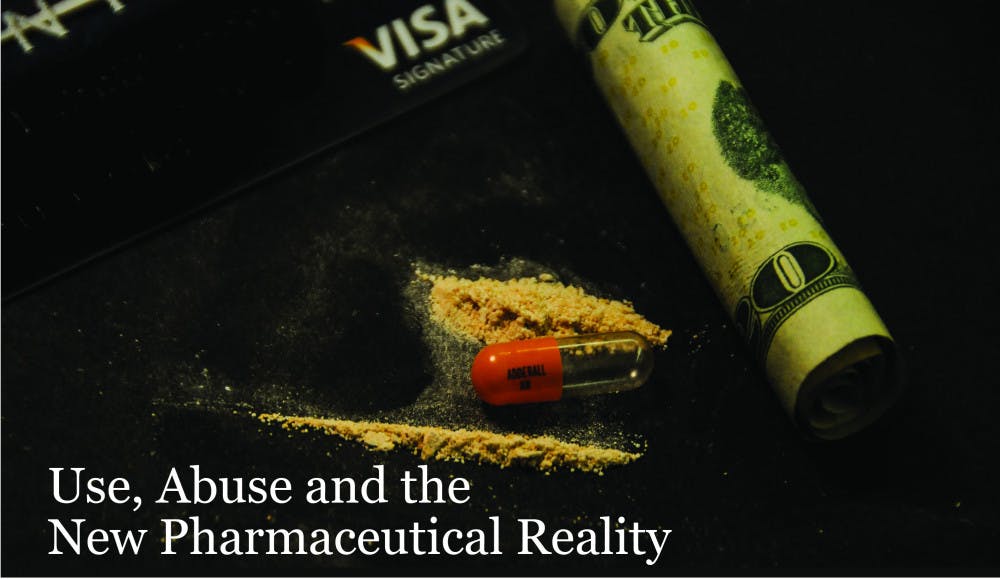

A friend took the orange 20-milligram (mg) pill and crushed it into a light powder with the bottom of a mug, before guiding the mass into four equal lines with a credit card and instructing Emma to get a tampon. She removed the applicator and blew her first line, beginning a recreational use that continues to this day.

“It was almost euphoric, it felt like I could do anything.” she said. “But the next morning, I had the worst hangover I’ve ever had in my life.”

More than two years later, Adderall has become a constant companion to Emma’s academic and social life.

“Recreationally, I wish I never tried it in the first place. Freshman year and the beginning of sophomore year before I tried it, I really liked just being drunk, and that was fine with me. Now in my friend group, that’s never enough. We can’t just all hang out and drink and go out. Someone always wants to do Adderall to take it to the next level.”

Emma’s story is one of an increasing number that point to a new reality across colleges and universities nationwide, as a wave of high-performing and highly stimulated students strive for top grades and are willing to do whatever it takes to get there.

Over the past 13 months, the Campus has followed numerous current and former students — all of whom requested anonymity and were given pseudonyms and, for some, different genders for legal and social reasons — as they grappled balancing their relationships with the powerful psychostimulant with academic, social and societal expectations. The Campus also interviewed experts on the frontlines, from psychologists prescribing the drug to neuroscientists studying their affects on the brain.

Data on psychostimulant use at the College is hard to come by. In a student-led study last spring, 16 percent of Middlebury students who responded to the anonymous survey reported illegally using the drug, slightly above the 5 to 12 percent estimated nationally. Of that percentage, only 4 percent reported having prescriptions. While the data is scarce, the stories of use and abuse paint a complicated picture, in which the line between prescribed use and illicit self-medication is murky at best and farcical at worst.

Whether Adderall is a life-changing medicine or an unfair performance enhancer depends on whom you talk to. What is clear is that we are now living in the Adderall Generation, a reality that is rarely talked about but apparent just below the surface. You may not have a prescription or snort the drugs on weekends, but psychostimulants are here to stay, and they have the potential to affect nearly every aspect of life at the College.

...

When Emma was diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in grade school, her parents refused to give consent for psychostimulant medication, instead resorting to behavioral therapy and tutoring. But when she got to the College, the workload became too much. After struggling to keep up as a first-year, she was prescribed Adderall as she went into her sophomore year.

When Emma was diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in grade school, her parents refused to give consent for psychostimulant medication, instead resorting to behavioral therapy and tutoring. But when she got to the College, the workload became too much. After struggling to keep up as a first-year, she was prescribed Adderall as she went into her sophomore year.“I remember the first day that I took it,” she said. “I felt really uncomfortable in situations other than doing work and didn’t really know what to do with my hands or where to look with my eyes, but when I was doing work it felt like I was in that movie Bruce Almighty when he’s typing on the computer really fast.”

She was first prescribed two 10mg fast acting Adderall a day. When she did not feel anything, the dosage was upped to 20mg three times a day. Her doctor told her to only take two pills a day, but prescribed her three to make sure she did not run out. Because Adderall is a schedule II controlled substance, Emma cannot fill her prescription across state lines in Vermont.

While Adderall has only been around since the late 1990s, psychostimulants have been ingrained in American culture. First discovered in 1887, they had no pharmacological use until 1934 when they were sold as an inhaler for nasal decongestant. Once the addictive properties of the drug became known, psychostimulants became a schedule II controlled substance in the early 1970s.

“If you look at the history of amphetamines, it was a miracle chemical, but they didn’t know what to do with it,” said Assistant Professor of Sociology Rebecca Tiger. “It couldn’t just be thrown on the open market, so they called it a drug, but then they needed to find a disease for it to treat. Amphetamines have been racing around looking for a disease because people want to use them.”

Psychostimulants regulate impulsive behavior and improve attention span and focus by increasing levels of dopamine in the brain. Dopamine is the neurotransmitter involved in natural rewards such as food, water and sex. Depending on the dosage, psychostimulants can boost dopamine levels 2 - 10 times more than a natural reward.

Put simply, dopamine is a key driver of happiness. The chemical is the key to many popular drugs — from opiates like heroin to amphetamines like MDMA. The release of dopamine in the brain after taking psychostimulants causes the euphoria users often feel. But when you constantly feed your brain dopamine, it can diminish your ability to make it independently.

While her grades shot up during her sophomore year, Emma felt the full force of the side effects. Growing up, Emma was outgoing and vivacious, but the Adderall made her reserved and quiet. As a result, she was often forced into a zero-sum game between academics and basic social happiness. Adderall often took precedence.

“I tried to avoid hanging out with people when I was on it, but that’s hard since it lasts a pretty long time, and then coming off it at night, it would make me really emotional and sad. It was really hard when I was coming down off of it to tell myself this is the Adderall and I shouldn’t actually be sad about whatever I was feeling.”

The sadness Emma felt after coming down from her Adderall is called anhedonia, or the loss of pleasure from things we naturally find rewarding.

As her relationship with the drug evolved, she learned basic parameters of what she could and could not do with Adderall. If she took it too late in the evening, she wouldn’t sleep. If she did not take any for a few days, she had to take it early in the day or risk insomnia. But when finals rolled around, all bets were off.

“Especially during finals, it got kind of aggressive. I would take it at like 10 p.m., work all night, go to bed at 4 a.m., wake up at a normal time, take another one, and continue doing work.”

...

There are more than a dozen different medications currently on the market to treat ADHD. While there are slight differences between medications, Adderall and Ritalin have become the poster children for psychostimulants. Emma has tried both.

There are more than a dozen different medications currently on the market to treat ADHD. While there are slight differences between medications, Adderall and Ritalin have become the poster children for psychostimulants. Emma has tried both.If the College has an expert on the psychostimulants, it is Assistant Professor of Psychology and Neuroscience Clarissa Parker. Before arriving in 2013, Parker spent 10 years studying genetic risk factors associated with drug abuse and dependence, including sensitivity to the reinforcing effects of psychostimulants such as methamphetamine in mice. Parker said one of her main concerns is younger and younger ages at which psychostimulants are prescribed.

“For me, the problem lies in the fact that so many people take it during a time when their pre-frontal cortex is still developing,” she said. “We know this part of the brain continues to develop into the mid-20s. When you combine that with the age group that is most likely to abuse drugs — high school and college — it’s dangerous.”

For big pharmaceuticals, stimulated minors means major profits. In numerous articles, the New York Times has reported on how the industry has lobbied heavily to push for medication over behavioral therapy.

“Studies have shown that there isn’t much long-term difference between Adderall usage and behavioral therapy for treating ADHD,” Parker said. “There are other ways to get the same effect, they just aren’t as immediate.”

Parker was quick to draw a line between people who take the drug responsibly under medical supervision and those who take it without a prescription, those who crush and snort their medication or those who take more than prescribed, repeatedly clarifying that the negative side effects affect those who abuse it. But Tiger thinks that line has little to do with medicine.

“The line you draw between people who need it and people who don’t is a cultural construct,” she said. “My interest is in who draws that line, and what their interest is in drawing it. People rarely use drugs the way they are supposed to, so in a way we are all abusing these drugs.”

...

Besides attending the College and taking Adderall, Max ’15 and Emma have little in common. A third-year lacrosse player, Max never encountered psychostimulant use while in high school, but quickly found it at the College.

Besides attending the College and taking Adderall, Max ’15 and Emma have little in common. A third-year lacrosse player, Max never encountered psychostimulant use while in high school, but quickly found it at the College.“I remember when I was a first-year, and I was in this kid’s room, and he was crushing up pills. I didn’t know what they were doing until he just told me ‘doing homework.’ They called it skizzing.”

With the stress of midterms building four months into his college career, Max took Adderall for the first time.

“I wrote a five-page paper in an hour,” Max described. “That’s when I realized, ‘this is nuts.’ There are a lot of athletes on different teams that can’t do work without snorting Adderall. Anything that requires putting your mind to: Adderall. That’s what steered me away from taking it a lot. I couldn’t get like that.”

Max does not have a prescription and estimated that he takes it five times a semester. Across athletics, he estimated that 60 percent use psychostimulants as a tool to get schoolwork done. When asked how easy it would be to obtain five pills, he took out his phone – “one text.”

In the 2013 survey, conducted by Ben Tabah ’13, over 20 percent of males reported experimenting with psychostimulants compared to only 10 percent of females. When asked about the difference, Parker noted that in animal models she had worked with, there were no sex differences in psychostimulant usage.

“You can teach a mouse to self-administer drugs, and there aren’t sex differences in the amount they administer stimulants like cocaine and dexamphetamine (an ingredient in Adderall) which suggests to me the issue is not about sex, but more about gender,” she said.

Social constructions around Adderall are apparent beyond just gender usage. Cocaine is often viewed as a whole different class of drug socially than Adderall, despite their similar chemical makeups, effects, and legal classification.

“Coke is scary to me,” Emma said. “It seems more intense to me because it is illegal and it could be cut with anything.”

“Coke is different than Adderall,” Max said. “The fact that [Adderall] can be prescribed to you means it’s not as harmful. The only downside is that you don’t sleep. That’s the only fight you face when taking it. If the amount of people taking Adderall were doing Coke, it would be considered a huge problem.”

Max is exactly the type of student Executive Director of Health and Counseling Services Gus Jordan is worried about.

“There is the notion that it is a quick fix, and that it’s safe because it comes in prescription form, but you are really playing the edge if you take these drugs without proper supervision,” he said. “We know that if you crush an Adderall pill, and snort it, it hits your brain in ways akin to cocaine, and with similar risks for dependence. This is such a powerful and potentially dangerous medication, that once it gets into a community and used in uncontrolled ways, people get hurt; you’re participating in that by selling or giving it away, and you don’t know if you will really harm someone down the road.”

In his 17 years at the College, Jordan has served in a number of student life roles and taught clinical courses in the psychology department. He said that psychostimulant use and abuse has only really come onto his radar in the past five years.

“Right now, it’s the hype about how great Adderall is that everybody seems to be listening to. But we don’t really know what happens when this drugs is used recreationally or without a prescription. I suspect that there are a lot of darker stories that aren’t being told, especially about the addictive qualities of these drugs, tragic stories that are buried out there.”

...

Asking Emma whether or not she would do it all over again is an impossible question for her to answer. Her views on Adderall are as complex as her usage. On one hand, she vehemently attests that without the drug, she would not be at the College. But she is acutely aware of the power the drug has, from sleepless nights to unwrapping tampon applicators time and time again.

“I think my path was necessary, but I don’t know if it was the right one in hindsight. I wish I didn’t have to take so much, but from trying all the other doses, nothing else really worked.”

Her parents know about her use because they pay for it, but have no idea about the recreational use — “they would be shocked and really mad.”

When asked whether or not she would let her kids take Adderall, she quickly said no before retracing her steps.

“Not until it got really bad, and not before the end of high school or even college. I think it’s going to get banned, or at least prescribed a lot weaker, just because it is addictive and being prescribed so ubiquitously,” she said. “It’s just going to end badly.”

Listen to Kyle Finck discuss this series on Vermont Public Radio.

Additional Reporting by ALEX EDEL, Layout Assistance by HANNAH BRISTOL, and Photos by ANTHEA VIRAGH