One chilly September morning in 2011, Kristin Lundy heard someone ascend her front steps and knock on her door. When she opened it, police Sgt. Mike Fish asked her to gather everyone living in the house. "Your son is dead," he said.

"I ran up the stairs," Lundy later recalled in an interview with the Burlington Free Press. "I just screamed until I went into shock...I thought he was coming out of the woods. I thought we were beginning to understand this opiate thing.” Joshua Lundy, at just 23 years old, had passed away from a heroin overdose.

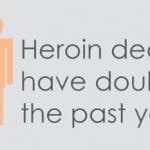

Sadly, Kristin's horror story is a tired one in Vermont. Statewide treatment for heroin addicts has increased 250 percent since 2000, and the number of deaths from by heroin overdose has doubled in the past year.

In last year's State of the State Address, Governor Shumlin asserted optimistically that Vermont was "... healthy, resilient, and strong. We are blessed to live here," he said, "and we care deeply about our shared future."

In his 2014 State of the State address, Shumlin's tone changed dramatically. "In every corner of our state, heroin and opiate drug addiction threatens us," said Shumlin.

Unfortunately, the stigma attached to heroin addiction makes it much harder for users like Joshua Lundy to get clean. Heroin addicts face intense social pressure to hide their addictions, and candid public discourse about heroin abuse is difficult.

In response, Governor Shumlin sought to reclothe the crisis as a medical emergency in his 2014 State of the State Address. "We must address it as a public health crisis," said Shumlin, "providing treatment and support, rather than simply doling out punishment, claiming victory, and moving onto our next conviction," he said. "Addiction is, at its core, a chronic disease."

Many health care professionals and recovering addicts agreed with Shumlin.

“I think that’s hard for some people that struggled with addiction to move on, if they’re always being labeled an addict forever,” said Gina Tron, a recovering addict and local journalist. “If you’re trying to fix a problem as a person or a state it should be something admirable instead of something to be looked down upon.”

“I imagined a heroin addict as, you know, some super-skinny guy laying on the ground in a back alley of New York City,” Tron said. Her perception began to change in 2002, when she heard about a high school classmate — a “very Vermont girl” — struggling with heroin addiction.

Dr. John Brooklyn, cofounder of the state’s first methadone clinic, refuted the idea of a ‘typical’ heroin user. “We think it’s some gangsta in a hoodie sticking up a convenience store,” Brooklyn said. “Not the person serving your coffee, pumping your gas or taking care of your kids at a daycare center.” In reality, Brooklyn knows recovering addicts at each of these professions.

In an interview with ABC, Dr. Richard Besser even asserted that the term ‘Ex- addict’ is a misnomer, because heroin addiction is a lifelong battle. All of the users Dr. Besser spoke with self-identified as “recovering addicts.”

The intensity of this battle is largely attributed to heroin’s extremely addictive nature. About one in four users becomes dependent after their first injection – an addiction rate higher than that of crack-cocaine or crystal methamphetamine.

Whether snorted, smoked or injected, heroin instills its trademark ‘blissful apathy’ by binding exogenous endorphins to opiod receptors in the user’s brain. After extended use, a heroin addict will no longer endogenously produce endorphins, and an ensuing dependency spiral can be lethal. Since opiod receptors are located in the brain stem — the part of the brain responsible for automatic processes like breathing — respiratory arrest is the leading cause of heroin related deaths.

Despite these dangers, “You’re gonna get hungry,” said recovering addict ‘Jen,’ who asked to remain anonymous during her interview with VICE. “Childbirth was nothing compared to kicking heroin."

Another recovering addict said that heroin addiction consumes all other priorities. “The first thing you think about [is] not feeding your kids,” she stated, “It’s how am I going to get high ... ”

Even heroin users brave enough to overcome the social stigma and seek help may not be able to find it. Over 750 people are relegated to wait lists at methodone clinics and rehabilitation centers across Vermont.

In order to supply this burgeoning market, smugglers have ramped up their efforts across the Northeast.“We’re seeing thousands of bags at a time, multiple raw ounces and grams, levels of heroin that we’ve never seen before” said Lieutenant Matthew Birmingham, the head of the Vermont State Police Narcotics Task Force.

Approximately two million dollars worth of heroin is trafficked through Vermont every week. Yearly, this means heroin smuggling is a 100-million dollar industry.

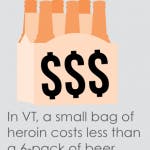

Even a small package of the drug can cause big problems. Heroin is most often sold in 25-40 milligram bags, or ‘folds,’ which are half the size of a sweetener packet. Just one kilogram of heroin provides nearly 30,000 of these bags.

Heroin’s pervasiveness can partly be attributed to Vermont’s geographic location. Interstate highways from Montreal, New York, Boston and Philadelphia all converge in Vermont, in what some analysts have described as ‘the perfect storm.’

During one sting, Burlington police and DEA agents traced Videsh Raghoonanan through his cellphone. The signal traveled from Burlington down interstates 89, 91 and 95 to Ozone Park, Queens. Less than 24 hours later, Raghoonanan retraced his path and arrived in Burlington before midnight.

New York is one epicenter of Vermont-bound heroin. Another particularly lethal type of heroin, known as “Chi” or “Chi town dope,” comes from Chicago. Authorities are often able to pinpoint the heroin origin because of signature ‘stamps’ on the packaging.

If the heroin comes into the state in its purest form, dealers will often cut it with other substances. “I’ve ripped people off by throwing hot cocoa in an empty bag,” ‘John’ told VICE in one interview. “Scoop a little dirt off the ground and throw that in there, dude.”

To make matters worse, some dealers have begun to cut their heroin with Fentanyl, a deadly synthetic narcotic. The powerful drug — between 50 to 100 times stronger than morphine — has been attributed to dozens of grisly deaths throughout the northeast, including three in Addison County. Some of these users were found with the needle still sticking from their arm.

In October of last year, Vermont state police arrested two New York smugglers in one of the largest busts in state history. When Marcus Davis and Eddie Eason were brought into police custody, Davis admitted to having bought 30,000 dollars worth of heroin in New York City.

If smugglers like Davis succeed, their potential profit margin is nearly impossible to comprehend. One dealer in Colchester buys heroin out of state for 6 dollars, and resells it in northern Vermont for 30, a markup of 500 percent.

Accordingly, the drug has brought organized crime with it. “There are real and legitimate organized gangs and organized criminal groups that are operating drug rings … and establishing themselves in Vermont,” said State Police Lt. Matthew Birmingham, commander of the Vermont Drug Task Force.

Still, a stronger police force is not the only solution, said Lt. Birmingham. “You can’t just keep arresting people coming in as runners,” he said.

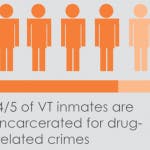

Already, 80 percent of Vermont’s inmates are incarcerated for drug related crimes. The state pays more to incarcerate its prisoners than it does on higher education.

Behind the empty syringes, plastic baggies and gun-toting drug dealers lies a darker reality: heroin addiction often starts with legally prescribed painkillers like Oxycodone.

The opiate crisis arguably exploded in 2010, when Purdue Pharma changed the formula of Oxycodone. By making pills harder to crush up and slower to dissolve into the blood, the pharmaceutical company successfully reduced prescription abuse, from 47.4 percent to 30 percent in the past thirty days. Yet in the same period, rates of heroin abuse nearly doubled.

“It’s like Whac-A-Mole,” said Barbara Cimaglio, Vermont’s deputy commissioner or alcohol and drug abuse programs. “We address one thing and then something else crops up.”

“Let’s be honest about this,” said Shumlin in an interview with ABC. “OxyContin and the other opiates that are now prescribed and approved by the FDA, lead folks to opiate addiction.”

Shumlin’s assertion was not just political maneuvering. According to one poll, 4 out 5 new addicts turned to heroin after abusing prescription painkillers.

Even more tellingly, Shumlin’s claim resonates with many current addicts. 32 year-old Andreia Rossi asked: “Why spend 80 dollars on an Oxy 80 when you can get a bag of heroin for 20 bucks?”

“You’re pretty much doing heroin anyway,” said another anonymous user. “It’s much cheaper than doing Oxys.”

In 2012, roughly a million doses of Oxycodone were prescribed in Rutland county alone.

“Not many things make my jaw drop, but this did,” said Clay Gilbert, director of Evergreen Substance Abuse Services. “[It] figures out to 17 pills for every man woman and child in the county.” Per capita, Grand Isle and Bennington had even higher prescription rates.

Furthermore, just like prescription painkillers, heroin can also be snorted and used intravenously. Combine this with its price and availability, and heroin is the ‘logical’ next step.

To parents who have lost their children to heroin, like Kristin Lundy, painkillers are far from logical. In an interview with The Burlington Free Press, Lundy recalled when her 17 year-old Joshua was administered morphine for a severe stomach bug.

“He lit up like a Christmas tree,” she said. “He said it was the best feeling he ever felt and that he wished he could do it forever.”

Lundy attended the sentencing for Kevin Harris, the smuggler who allegedly sold her son the deadly heroin, five years later. Harris was born in a jail, and both of his parents died before he turned 11.

“I’m sorry you didn’t have a good childhood,” read Lundy’s statement to Harris. “We have something in common. We have both suffered great loss due to drugs and addiction. My hope for you is that someday you will experience the love I felt for Josh, and that he felt for his daughter.”

Local Westland native and rehab worker Michelle Flynn was concerned for her own children. “It scares me for people’s well being that it’s this available,” she said in an interview. “I have two young kids – 18 and 20 year old boys – who have not found [heroin], which I am grateful for. But it scares me for that generation. Your generation.”

“I know what addiction life is like,” she recalled, “and I wouldn’t wish that on my worst enemy. It’s not an easy change to give up on what used to be mind altering. What used to be your escape.”

Paramedics and EMTs on the front lines witness this loss firsthand. When the heart and lungs have stopped, a quick response is critical. Permanent brain damage can occur after 4 minutes without oxygen, and death just 5 minutes later. And even by medical standards, heroin overdoses can be messy. EMT Lisa Northup recalled when one semiconscious patient began to vomit onto her on January 9.

“I kept talking to him,” said Northup, “telling him he was going to be alright. I mean, that’s just what we do.” The patient was lucky. Just hours later, Middlebury Regional EMS arrived too late for another heroin victim. For him, “Everything we could do we had done,” recalled Paramedic Kevin Sullivan. “Unfortunately, he had been down too long at that point.”

Consequently, one wonder-drug has helped pull many patients back from the brink of death, including the Salisbury patient that Northup revived. Naloxone hydrochloride — whose trade name is Narcan — is an µ-opioid antagonist that kicks heroin off opiate receptors in the brain.

The drug is administered intravenously by paramedics, or nasally through a device known as an atomizer. The effects of the drug, which untrained civilians can administer, are almost immediate.

Mike Leyden, Deputy Director of Emergency Medical Services at the Department of Health, said the atomizers are an ‘infallible’ safety net. “[They’re] a good reliable safe route,” he said. Still, since heroin in the patient’s system can outlast the Naloxone’s effects, administration should always be accompanied by a 911 call.

In 2013, Vermont Legislature passed Act 75, which aims to provide a “comprehensive approach to combating opioid addiction and methamphetamine abuse in Vermont ... ” As a result of the legislation, the Vermont Department of Health began developing a statewide pilot program to distribute Narcan, which is now available at many health clinics.

“They’re just going to hand it out to folks,” said Chris Bell, director of emergency medical services at the Vermont Department of Health.

“It is a relief for any family member to know there is something they can do immediately if that horrible occasion might occur,” said Nancy Bessett, who lost her husband to heroin last November. “I will always feel guilty because I wasn’t there. If I had been there. If I had Narcan. Maybe I could have revived him.”

For legislators and medical professionals, preventing overdoses is only part of the battle. Establishing programs to rehabilitate heroin users may prove to be an even larger hurdle.

One such positive initiative is Chittenden County’s Rapid Intervention Community Court (RICC). The program is designed to allow addicts to avoid further prosecution if they accept medical treatment shortly after their arrest. Governor Shumlin has called the program a ‘humane’ option for heroin addicts.

After attending just 90 days of counseling, drug treatment and life skills training, RICC attendees can get their charges dropped. At its best, the ‘pre-charge’ initiative helps recovering addicts avoid a criminal record and take back control of their lives.

Heroin users tried in conventional courts often reoffend shortly after their trials. RICC reduces recidivism by focusing on repeat offenders with no violent record and a clear indication of addiction.

“What we’re trying to do is break the cycle,” said Chittenden County State’s Attorney T.J. Donovan. “We can do the same thing that’s not working, or we can do something different.”

The program is effective: only 7.4 percent of recovering addicts that completed the program reoffended. Of those who did not, 25 percent reoffended.

Despite their success, the novel programs are imperfect. Not everyone who applies is accepted, and rapid intervention is harder to implement in rural areas where applicants cannot easily commute.

Emmet Helrich, a manager at the RICC, said the program strikes at the underlying trigger of criminal activity: the user’s health. “Forget about the court case,” Helrich said. “Get healthy.”

Anonymous recovering addict and Burlington mother ‘Jessica’ appreciated the second chance.

“I just needed somebody, one person, to give me a chance and have a little bit of hope,” she said.

Inspired by the success of RICC, Addison, Lamoille, Rutland and Franklin counties have begun to implement similar programs. Governor Shumlin advocated investing $760,000 to expand and strengthen the programs.

Like Shumlin, Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick labeled opiate addiction a public health emergency. “We have an epidemic of opiate abuse in Massachusetts, so we will treat it like the public health crisis it is,” Patrick said in a statement.

Because of the interstate nature of the crisis, officers from across the Northeast convened to discuss cooperation. On March 28, roughly 90 officials from Vermont, Massachusetts, New York, as well as members of the US Drug Enforcement Administration and Department of Homeland Security met at the Sheriff’s office in Washington County, NY.

The discussion largely focused on two heroin pipelines, Routes 149 and 4, which pass through Washington County into Vermont.

“This will also help us exchange information and tie all the pieces together,” said Washington County Sheriff Jeff Murphy.

Officials determined routes of travel, trends in drug distribution, and began to formalize a cooperation agreement.

Still, Shumlin recognized that solving the heroin crisis in Vermont will take more than just good police work. “We’ve got to stop thinking we can solve this with law enforcement alone,” said Shumlin in an interview with ABC.

Imprisoning a heroin dealer in Vermont is incredibly expensive – around $1,120 a week – or ten times the weekly cost to treat an addict at a state-funded center.

“Today, our state government spends more to imprison Vermonters than we do to support our colleges and universities,” noted Shumlin in his State of the State address.

To many officials, this is an untenable path. Rutland beautification project Rutland Blooms has responded to the influx of heroin with a resilient positivity. The beautification project plants flower gardens around Rutland. It was established by Green Mountain Power and Rutland officials to “highlight the community’s incredible spirit and beauty.”

Yet, Rutland Blooms is more than just flowers. According to their website, the organization consists of over 50 local groups all intent on “supporting and increasing the sense of community that will be necessary to solve the issues the city faces.”

Rutland Mayor Chris Louras has helped spearhead the effort. “This is one more step in efforts to improve the economic and social climate of the community,” Louras said. “Its impact will be visible and symbolic. The outpouring of interest, even before today’s announcement as GMP quietly began planning, has been extraordinary.”

This sense of community is important, especially to those who have lost loved ones to the drug. Skip Gates, whose son Will was studying at UVM when he overdosed, now works to spread awareness of the devastation heroin can cause.

“I never knew anything in human experience could be this hard,” Skip said. “I never knew any human being could feel this much pain. It has redefined the rest of my life.”

In his 2014 State of the State address, Governor Shumlin explained that Skip “speaks for all grieving families.” At the end of the speech, Shumlin called the state to arms: “All of us, together, will drive toward our goal of recovery by working with one another creatively, relentlessly, and without division. We can do this. I have tremendous hope for Vermont, and for our efforts to overcome this challenge and keep the Vermont that we cherish for generations to come."

Graphics by OLIVIA ALLEN