I hope I will not appear as too much of a nerd by assuming you know about the world famous Italian plumber Mario. Mario spends his time jumping on turtles and saving Princess Peach in the aptly named “Super Mario” video games. By today’s standards Super Mario is a quaint game as it contains no guns, no real violence or realistic blood splatters. Cartoon characters make funny noises when you jump on their heads and the whole premise is outlandish and whimsical. Mario saves the princess and that’s all there is too it.

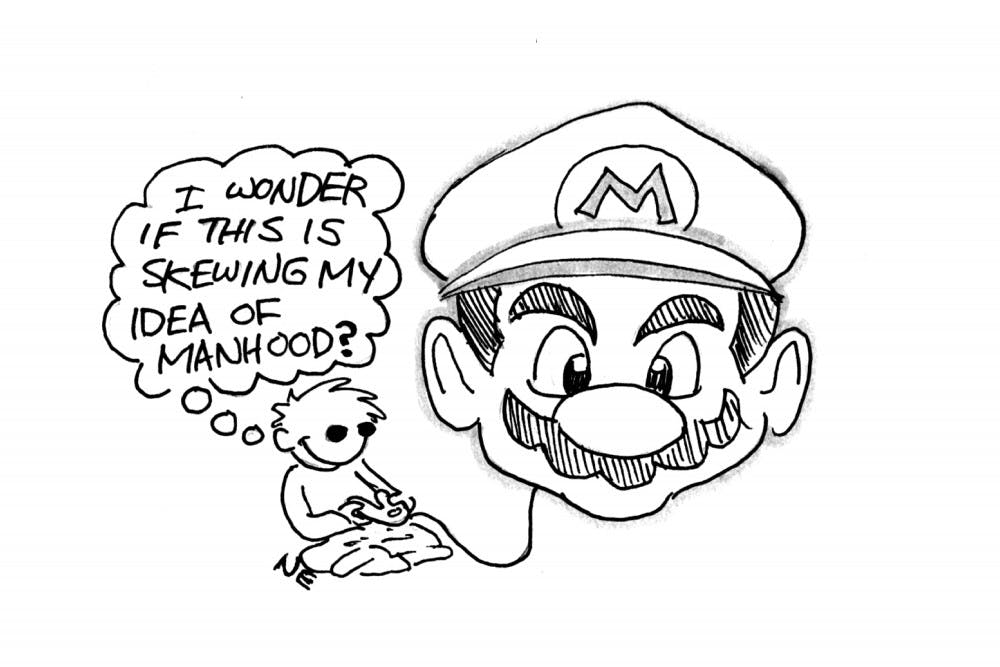

Why is this children’s (or college student’s) game of any consequence? Having two older brothers and a grandmother that liked to dote on us, video games were a fixture in my childhood. For that matter, some of the easiest stories to understand were things like Dr. Seuss and Mario saving a princess. What I did not know was even at that time I was beginning to form my conceptions on how men interact with women.

One of the real tragedies of male adolescence is that these unsaid messages begin to manifest. I’m not going to blame it all on Mario, movies and books did a lot of it too, but certainly I began to think that nice guys always got the girl. That if you persisted long enough in being nice she would eventually give in. In so much of our dialogue concerning sexism and sexual assault we assume a dramatic aggression on the part of male figures. We give little thought to obsessive, perhaps under-developed, not so popular boys who too are putting together a system for how they will later interact with women.

This of course is not something new. After all, how many little girls want to dress up as princesses? How many men grow up expecting a devoted sexual partner? This particular narrative is at once dangerous and disturbing. Yes, society has a clear interest in subduing aggression in the male population, but what do we replace it with? The not so subtle replacement is merely reward for good behavior. The villains will never win and the “good guy,” the one who was there for her when she cried, who offered to beat up the guy who made her cry, the one who sat on the phone for her for hours, will naturally end up with her. If we follow this logic through we end up in distressingly familiar territory, men believing they deserve sex as a reward for their good behavior.

If we could solve this problem it would go a long way towards creating healthier, more stable relationships. No matter how hard we scream, or perhaps how many op-eds we write, simply launching anger will not effectively change the way male self-esteem is formed. It is a far more difficult thing to raise our sons to be courteous, temperate and patient for their own sake, with no reward in mind. This is something churches and governments struggle with, let alone parents. The stories we have told children for hundreds of years enforce men as agents, deserving reward. So what if we just started telling different stories? Would my toddler self enjoy a game about Princess Peach? Maybe we could have fantasy novels with sincere heroines and not sexual caricatures?

It Happens Here is on Nov. 10 and if things repeat themselves, we’ll hear a lot of powerful, often emotionally difficult stories of sexual assault. For those of you that go, ask yourself this: would these situations have been avoided if men had a better image of how they see themselves? I am convinced that if we removed sexuality from what it colloquially means to “be a man,” we would take an enormous step in solving the problem of sexual assault. Keep in mind too that direct sexual assault and violence is one thing, the less obvious issue is the quiet young man believing he will one day be rewarded for his good behavior.

To redeem the video game industry a little, I have to admit that while it is still a male dominated industry, great strides have been made. The ability to play as male, female, gay or straight has become a recurring trend in many games. So it’s not all Mario and the princess. We can tell better stories as students and as a culture. We can tell stories about heroines with normal sized breasts who fight crime, we can tell stories about men who don’t need a woman’s affection to still consider himself a man. Maybe, the Princess got sick of waiting in her tower and maybe the handsome Prince simply helped her down and proceeded to go about his business without thinking much of it.

Artwork by NOLAN ELLSWORTH