Have you seen the movie Boyhood? I watched it on my plane ride back to school this January — United had free movies for once, shocker! — and the film left an impression on me.

For those who don’t know, it follows a boy, Mason, over a twelve-year period as he grows to be an adult. Boyhood therefore doubles as a sort of societal documentary, spanning from 2002 to 2013. That chronology aligns perfectly with my own growing up. I, and all other 90s babies from the year of the dog or year of the pig, experienced our righteous tween and teen years during that period.

While I was able to appreciate the expired trends the movie brought back to life — 1990s Volvo station wagons, Soulja Boy songs and the iPod Mini just to name a few — the final product, an 18-year-old Mason, evoked a less empathetic response from me.

Mason embodied a sentiment my generation seems all too familiar with: ambivalence. Whether it was seen through his low number of smiles and laughs or his lack of involvement and interest in activities and people, Mason didn’t bring a whole lot to the table, and what’s more, he didn’t seem to care.

I asked a few of my friends if they knew this type in real life — the kid vegging out on Thursday afternoon, Netflix remote in one hand and cellphone in the other. He texts “LOL” back to a friend without actually cracking a smile. The sun beats into his bedroom, highlighting the dust on the TV screen that his mom asked him to clean a few days ago.

Seem familiar? Seem sad? The image does not preview that generation of change-makers for which our predecessors have stressed a need. Gone is the generation of dreamers, replaced instead with a level of contentedness and lethargy we have not yet earned for ourselves.

Our planet’s temperature rises with each passing day, technology poses increasingly dangerous threats and our American government remains as called upon as ever, yet historically unproductive. These unsustainable trends make our generation the linchpin of progress; we just need to take on the challenge.

Some events have recently demonstrated clear social objectives, like the climate march last fall. These social uprisings are reminiscent of past student protests — civil rights, anti-Vietnam War, et. cetera — and they are one way to counteract the ambivalence that runs rampant in our generation.

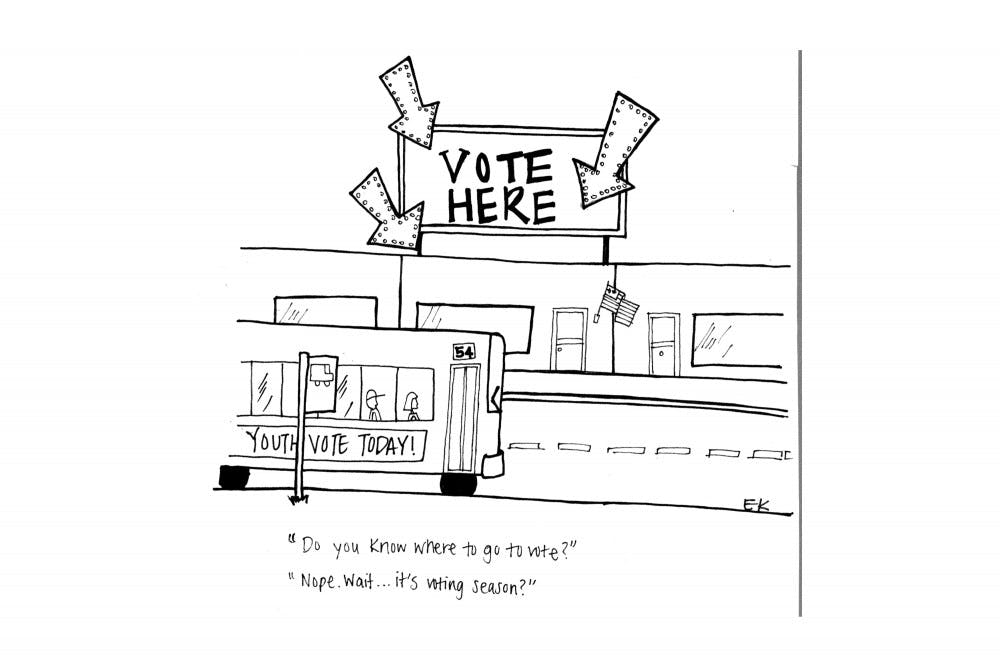

There is, however, another, even easier way to stay involved in public life: voting.

For some reason that I cannot fathom young people (aged 18-24) have had historically low voter turnout rates since gaining the right to vote in 1972. In 2012 only 41 percent of young people came out to vote. This is no small thing — the “Millennial generation” makes up a quarter of the electorate! — stressing the potential influence young people could have.

So, we return to that dude watching Netflix and texting in his room. I can’t tell you the number of my peers who were that guy this past midterm election, too lazy or “busy” to vote. I myself came close to being that guy after seeing the paperwork, trips to the post office and research involved with voting by mail.

But then I remembered the outcome of voting. I remembered that I might not be deeply impassioned about that proposition on medical malpractice suits or even who the lieutenant governor of my state was (am I the only one who doesn’t know what they do?), but doing a little research and casting my ballot kept me in the game of democracy. Voting on (sometimes seemingly unimportant) issues might not have changed my life, but it helped make sure that I lived a life that could one day incite change. Because it all comes down to this: when we do not vote, we disenfranchise ourselves; individuals lose their say in political life and extremist groups accrue concentrated power.

This wasn’t exactly a partisan political argument, as is normally the nature of this column, but I felt it an important enough issue to set the tone for this new year of writing. While I myself cannot claim to be above this youth ambivalence that I have laid out, I still want to highlight it. As Middlebury students, we all like to think of ourselves as educated, involved world citizens, but I think we must also keep in mind the privilege and ease of living that we experience in this 14-square-mile New England utopia. While it’s great to push the Real Food movement through campus, partner with Divest Middlebury and the like, let us not forget about an even more basic yet overlooked way to stay involved: the civic duty of voting.