Barak adé Soleil crosses to the middle of the stage. The Chicago-based artist smiles infectiously at the audience. “I’m going to ask you to come closer,” he announces. His deep baritone instantly comforts you and makes you trust him. “There is plenty of space up here with me.” A moment of silence ensues, then the sound of one hundred people standing up, grabbing their bags and relocating to the front of the hall. Students hop onto the stage, curling up two or three feet from a still-beaming Soleil.

Suddenly, this is not a lecture. It is a conversation, reminiscent of those summer camp gatherings where you sing songs and roast marshmallows around the fire. Soleil could almost be a student, at least based on the “non-hierarchical space” he has created. Almost. Except then you remember that his legs are thin compared to the rest of his body. That not even the smallest of scuffs tarnishes the pristine surface of his powder blue suede shoes. That he sits there with the rest of us, not on the ground, but in a wheelchair. For all of the College’s attempts to diversify the student body, the physically disabled are extremely under-represented here.

Soleil’s “keynote performance” kick-started the 2015 Clifford Symposium, named in honor of Nicholas Clifford, longstanding professor in the History Department at the College. This year’s theme was “The Good Body,” challenging attendees to consider the process behind how society defines bodies as good or bad. Like many other attendees, Xuan He ’19 was somewhat surprised by the breadth of the discussion.

“I went into the symposium expecting to be lectured on body image issues,” she explained.

In the end, presenters throughout the three-day-long symposium challenged students to think beyond that, covering material related to race, sexual identity, class distinctions, history, education and many more concepts.

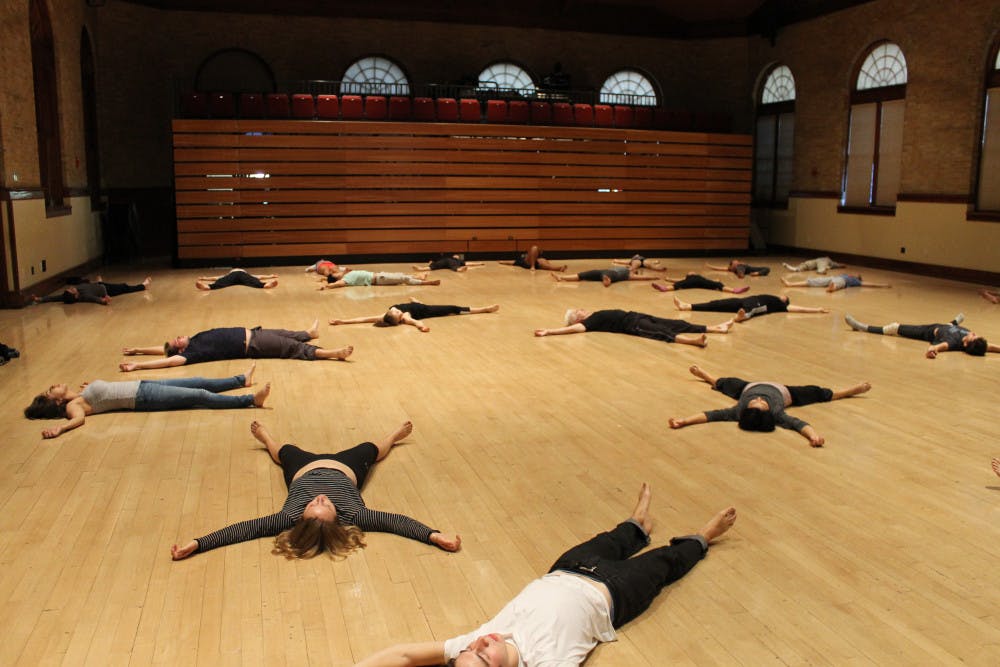

The mediums used for the expression of these ideas were also diverse. Some sessions featured lecturers, others consisted of film screenings. Dance Professor Andrea Olsen held a workshop that combined writing and dance, while choreographer Maree ReMalia provided a class on the Gaga “movement vocabulary.”

After inviting audience members to text him with their thoughts or comments, Soleil began his presentation by asking questions:

“What is a good body?” he wondered. “Is it thin? Is it a race? Is religion attached to it?” He paused, then delved deeper. “Do I have to be pretty to be a good body? Do I need to stand to be a good body, or can I lie on the floor?” At that point, he glanced at his phone. “I’m going to read this text out loud,” he announced. “Is a good body about me, or you?” Soleil considered a moment, then sighed. “Or is it about us?”

He then proceeded to tell a story on the “unfinished legacy” of the racialized, disabled body. He spoke of slaves, confined to a three foot by three foot space for months on end as they made the journey across the Atlantic to the New World.

“Can you imagine how good their bodies must have been to survive that?” he asked. “Good for work. For beating. For sexing. For selling.”

He brought up the history of exhibiting blacks in freak shows and circuses, telling the stories of both Joyce Heth, the supposed 161-year-old nurse of George Washington, and Saartje Baartman, also known as the “Hottentot Venus.”

He spoke of a “mixed” woman who underwent a stringent examination of not only her physical features, but also her sexual purity, her way of speaking and her ability to dance, all in order to pass as a white woman.

“Why do we keep trying to beat the body ‘good’?” Soleil lamented. “We keep trying to make it work, to make it good, to make it docile and tame.”

These sentiments were echoed in the symposium’s other presentations. Eli Clare, a self-proclaimed genderqueer with cerebral palsy, pointed out that the continuous scientific focus on “the cure” implies that certain bodies are “just fine,” while certain others need to be “fixed.”

Using Caitlyn Jenner as an example, Anson Koch-Rein, Visiting Assistant Professor of Gender, Sexuality and Feminist Studies, spelled out how only bodies that sustain one’s gender are deemed legitimate by society. Jenner took the extreme route in order to “fix” her body, to make her body “work,” undergoing surgery to legitimize its relationship to her gender.

Overall, the symposium stressed the relationship between social inclusion and the “good” body.

“We define good bodies by thinking about bad bodies,” Clare stated, explaining that interpretations of good and bad bodies are “grounded in systems of privilege and power.” By defining certain bodies as good and others as bad, by trying to “fix” bad bodies, we inevitably deem some people as belonging, and some others as not belonging.

Clare called on the specific example of higher education in order to relate this issue to the students in the audience.

“Whose body-minds are worthy of sitting in the classroom? Whose body-minds build the buildings? Mow the grass? Clean the bathrooms? Whose body-minds make that classroom possible?”

Much of the student body seemed to accept the idea that society arbitrarily created answers to these questions. In a view representative of many attendees, Gram Bonilla ’17 declared that Soleil “put it best,” when he stated confidently, “When I look at the disabled body, all I see is goodness, truth, people living their lives … The disabled body is good. I am simply in a social construct that is disabling.”

Beyond Body Image Issues: 2015 Clifford Symposium Re-Defines “The ‘Good’ Body”

Comments