Literatures and cultures librarian Katrina Spencer is liaison to the Anderson Freeman Resource Center, the Arabic department, the French department, the Gender Sexuality & Feminist Studies (GSFS Program), the Language Schools, Linguistics and the Spanish & Portuguese departments. These affiliations are reflected in her reading choices.

“While I am a very slow reader, I’m a very critical reader,” she says.

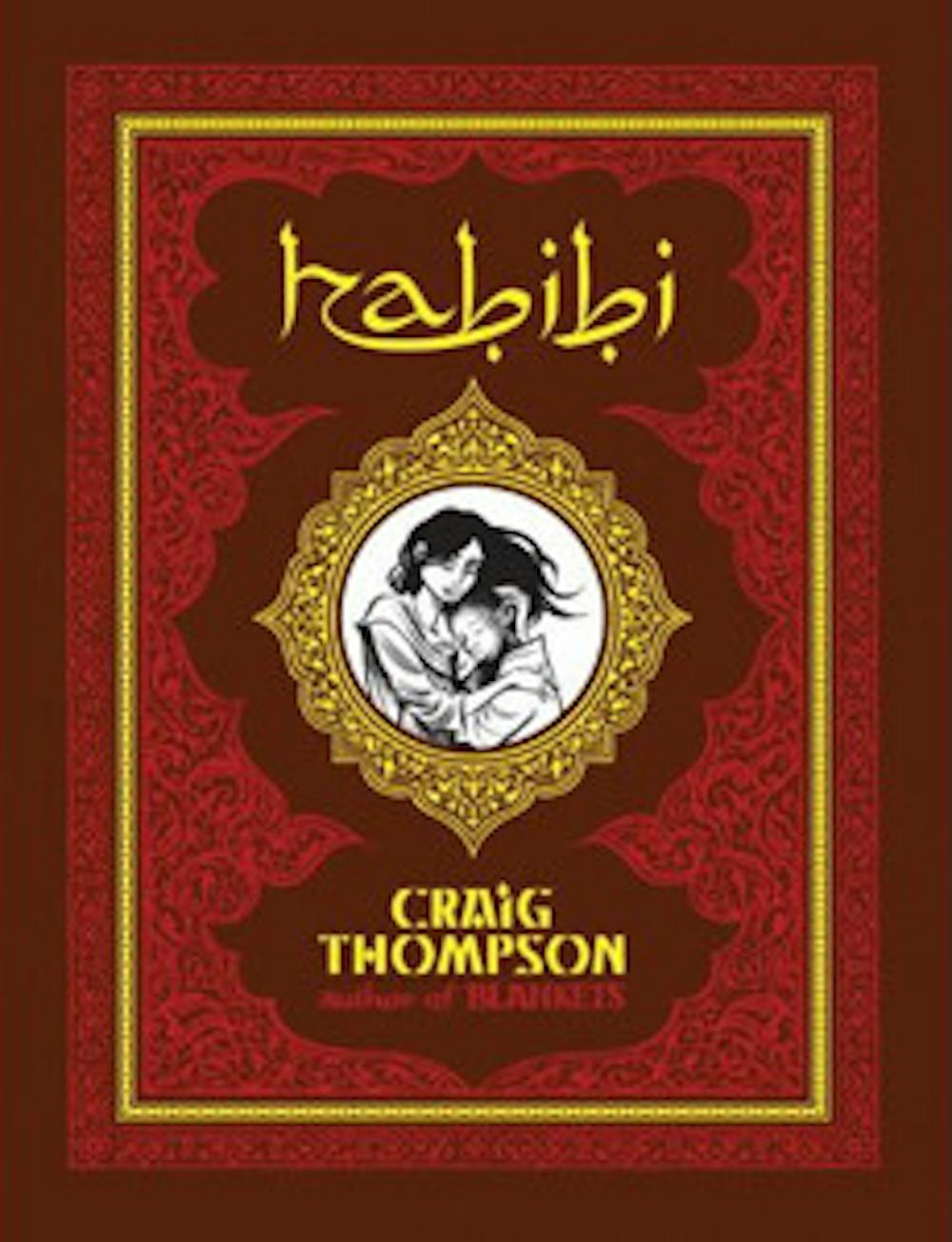

habibi

by Craig Thompson, 2011

672 pages

Trigger Warnings: Multiple scenes of rape are visited in this work. There is also a good deal of partial female nudity.

The What

“habibi” is a graphic novel that tells a fantasy tale of love in the fictional land of Wanatolia, a landscape that is both desertous and urban, “timeless” and modern and distinctly Middle Eastern in aesthetic and tradition. Dodola, the female protagonist, is sold as a child into marriage and saves a baby, Zam, a black African, who was headed towards a similar fate of slavery, subjection and oppression. Making a daring escape from potential captors, Dodola raises Zam in isolation from society.

Her engagement with the rest of civilization (spoiler alert!) involves her exchange of sex for provisions. After years, this set-up begins to fail and leads our characters down paths of new adventures when the two become separated. These include Dodola’s navigation of a palace harem where she becomes the object of a lusty sultan’s desire and Zam’s adoption into a band of hijras who believe in castration and harass society into giving them alms for their survival.

Yes, there’s that much going on in the work! Rape, suggestions of incest and a battle for water rights are all interwoven by sacred scripture from the Qur’an, parables and tapping into a rich tradition of storytelling from Arabia.

Visually the text is intoxicatingly gorgeous even in its monochrome. The visual appeal is the least disputed of the the book’s characteristics among critics. Despite not knowing the Arabic language, Craig Thompson learned the alphabet (abjad) and its ligatures and employs them alongside Middle Eastern motifs like ornate tile design to effectively conjure the feeling of having traveled elsewhere for his Western audience. Truly, if the tale had no words, merely looking at the text would be a treat for the eyes.

The Why

The tone is visually arresting. Its design, deeply maroon and textured, makes one feel they are encountering something special and unique. On the cover, Thompson melds English and Arabic in the strokes he uses for the letters in the title. That alone had me. Unlike German or Spanish, one of the initial features that attracted me to Arabic was that I couldn’t decipher it: I couldn’t read it, pronounce it or make any sense of it given my ignorance of the alphabet. So when I saw this work, “habibi,” a popular term of endearment meaning “my beloved” or “my darling” (for males) used by Arabic speakers, it drew me in. Having become a working adult, I had to violently tear myself away from my love of language study. So now, when I can fit in a brief and fleeting moment to make love and draw near, I do. This was one of my chances to do so. [Note: Don’t ever grow up. #srsly]

I wanted to like this work. It is meritorious for its sheer beauty and naked ambition alone. It is over 600 pages worth of drawing! However, in reading this work, it is as though the author had never heard of Edward Said and “Orientalism” before.

The narrative relies on dangerous tropes that ring of colonialism, exotification and a global divide. In comparison to the values we espouse today in the 21st century, the work is strikingly anachronistic in its representations of women, Arabs and the Middle East. It’s as though Thompson mined every stereotype he could find that casts the white, Western gaze over the Middle Eastern region and said, “Yes, I want that in story! Naked, lounging women here! Shisha pipes there! And many camels in a caravan! Yes, I want it all!”

Moreover, while allusions to the Qur’an, the Bible and “1,001 Arabian Nights” appear throughout the work along with cryptic mysticism, parables and talismen, it’s unclear what the author wanted to accomplish with them. They add to a sense of otherness and geographic distance but their objective beyond these is vague and beyond my comprehension.

While I would happily consume this artist’s graphic work in another publication, I’d hope that he’d collaborate by letting someone else lead a more modest venture in text-based storytelling and he, himself, assume responsibility for drawing. He must work harder by many measures to more fairly, accurately and humanely depict people who are not white or male. In a text that approaches verisimilitude in its late chapters, it leaves much to be desired elsewhere in the narrative. For a different taste, see the author’s 2003 memoir release “Blankets” that received more critical praise.

The Librarian Is In

Comments