On Thursday April 5, the Howard E. Woodin Environmental Studies Colloquium Series hosted a lecture by Kara Lavender Law, PhD, titled “Open Plastics Pollution from Sources to Solution.” Over the course of the lecture, Law presented findings from her decades-long career as a research professor of oceanography with SEA Semester and her expertise on ocean circulation and marine debris, addressing common misconceptions about ocean plastics pollution and providing her own insights into the causes of marine debris and the steps we can take to reduce it.

Law was quick to acknowledge that marine debris pollution is frequently characterized by the looming presence of The Great Pacific Garbage Patch, an area of intense marine debris concentration that is said to be larger than the state of Texas. While subtropical ocean zones do have higher concentrations of marine debris due to the convergence and stagnation of currents from the equator and poles, Law asserts that the view of garbage patches as the predominant sources of marine pollution is misleading. She instead points out that human-made debris permeates every part of the world’s ocean, having been found across every latitude and depth of the ocean.

Unsurprisingly, plastics, and more specifically, microplastics, are the most commonly found form of marine debris. The term “microplastics” is used to denote smaller pieces of plastic that are frequently found to be the remnants of larger plastic debris that has been degraded by sun and weathering. Unlike the floating debris commonly seen in garbage patches, microplastics inhabit practically an unlimited range of marine environments, according to Law, and are not particularly visible or easily spotted from the air. Since 1972, microplastics have been detected in increasing numbers and found even in locations that are incredibly remote from human populations, such as the deepest levels of the ocean and in frozen arctic sea ice. Although microplastics may in some ways seem preferable to larger and more blatantly disruptive debris, recent research has indicated that both types come with their own environmental impacts, despite much still remaining unknown.

According to Law, encounters between marine animals and plastic debris are well documented. At least 50 percent of all seabirds and mammals have been recorded interacting with plastic debris, and there have been documented encounters of every species of sea turtle with marine plastic debris. Law says, however, that the effects of these encounters are myriad. Old fishing gear is a common cause of injury and death among larger sea mammals that get irreversibly trapped in the abandoned equipment.

Floating plastic can also become colonized by fish species and barnacles that will follow or attach to the debris as it drifts long distances, which likely increases the spread of invasive species. Recent research has shown that even microplastics frequently contain a biofilm of microorganisms that are significantly different from the community of microorganisms in the water surrounding the plastic.

Additionally, ingestion has become a common problem among sea birds and large sea mammals, such as whales and sea turtles that ingest plastic resembling prey. This behavior can lead to accumulation within the stomachs of animals, sometimes leading to starvation and malnourishment. Law warns that the ingestion of plastic debris by fish is particularly concerning for humans who eat seafood, because the chemical behavior of plastic additives is poorly understood.

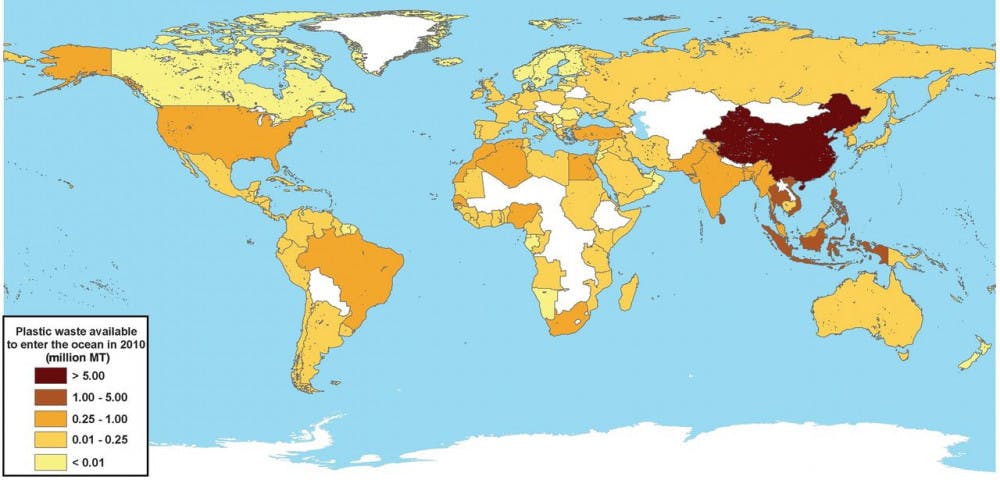

The root of the problem, says Law, is a recent one, as “production of plastics started around the 1950s and 90% of the plastic produced since then is still in existence.” The statistics of modern plastic usage are truly staggering in contrast with the relatively short history of the material. Although our grandparents may have known a world completely free of plastic when they were young, a recent study published in Science magazine by Law and her colleagues estimates that eight million tons of it, the weight equivalent of how much tuna is extracted from the oceans each year, annually enters the ocean from land.

This study also showed that China and some other countries in southeast Asia are the largest producers of plastic that enters the ocean from land. Law made sure to stipulate that the position of these countries as leading producers of marine plastic debris is not a result of higher plastic usage, but a result of improper waste management. While many regions of these countries are still in the process of developing suitable infrastructures for their growing economies and waste streams, the United States remains a noticeably large contributor to marine plastic pollution despite its reputation as a country with well-developed infrastructure.

Law points out that most ocean plastic is a direct result of mass consumption of plastic goods that turn to waste almost immediately. While proper waste management is an important step that needs to be taken towards limiting the entry of plastic into the ocean from land, much of the responsibility for reducing plastic pollution must be placed on consumers. Unfortunately, “there is no silver bullet,” Law said. Consumers have few options outside of the three R’s: reduce, reuse and recycle. She also recommends participating in “The Last Chance Capture,” or taking any opportunity possible to properly dispose of waste before it enters the ocean and trying to raise awareness of the issue when possible. Law makes the point that plastic production relies on consumers, and we have the ability to impact behavior just by using responsibly and purchasing from producers that take end-of-life responsibility for their products.

There is still much that remains unknown about the future of the oceans in relation to plastic. Law’s research suggests that the amount of plastic debris entering the ocean each year will only increase, but the implications for the future of marine species and the health of coastal communities are extremely uncertain.

“We’re just doing a grand, global experiment, and we don’t know what is going to happen,” Law said.

The Problem with Plastics

Comments