The debate about data privacy unfolding in national newspapers and the halls of Congress has finally reached the college on the hill. This time, privacy advocates have something to rejoice in.

In a memo last week, the Davis Family Library announced it would not keep records on borrowing history for patrons. It was not a policy change, per se — in fact, the library has never stored this data. But while the library was upgrading its catalog software this semester, staff had the choice to change its data policy.

Storing the data could allow the library to better manage its collections, or to suggest to patrons other materials based on their reading habits, wrote Michael Roy, dean of the library and the author of the memo. Despite these potential benefits, the library staff opted for privacy.

“The library has never stored any information about material individual patrons have checked out once the materials are returned to us,” wrote Roy. “We believe that not storing that information at all is the best way to protect patron privacy.”

The library, built in 2004, houses about 600,000 volumes, as well as historical Vermont documents, the college archives and U.S. government publications. It also maintains digital collections and is a member of Interlibrary Loan.

Roy’s memo comes weeks after The New York Times reported that the personal data of 87 million people had been improperly shared with Cambridge Analytica, a political consulting firm aiming to build a voter profile of the American electorate. Days later, Mark Zuckerberg, founder and CEO of Facebook, faced scrutiny from lawmakers in Congress about his company’s mishandling of data.

Increasingly, technology has upended norms of privacy, which is often outweighed by the sheer ease of digital surveillance. At Middlebury, the IT department faces the same moral dilemma when it configures new systems, Roy said.

“The technology is voracious,” Roy said. “It wants to record every keystroke. You really have to work against that impulse if you want to be thoughtful about what information you keep.”

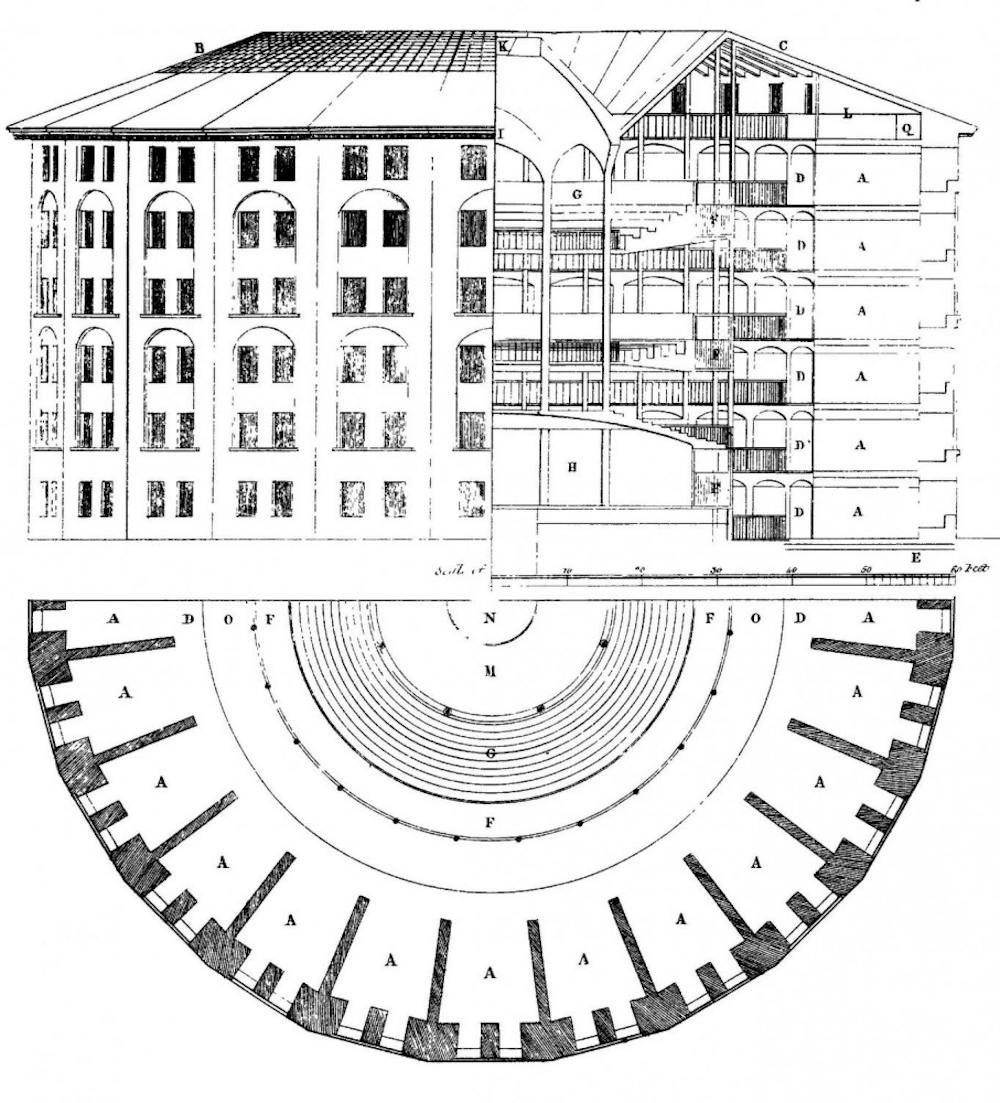

In his memo, Roy included a diagram of the panopticon, a prison scheme developed in 1791 by Jeremy Bentham in which every prisoner is visible to a central watchman at all times. In the panopticon, inmates have no privacy — and they cannot tell when they are being watched.

The panopticon diagram has an uncanny resemblance to the library’s architectural plan, which is depicted in the 75-foot-wide mural hanging in the atrium, “L’Art d’Ecrire.” But the library functions as exactly the opposite of Bentham’s panopticon, Roy said.

“The culture, the tradition of librarianship is all about patron privacy and freedom of expression, freedom of inquiry,” he said. “It’s the place where you can go to bump up against new ideas and difficult ideas, and it’s a place where you can do that in private. There’s nobody watching you, there’s nobody checking on what you’re reading.”

If Bentham were alive today, he would probably say the building most like a true panopticon is Old Chapel, the center of administrative power whose cupola offers a 360-degree view of campus that is live-streamed online 24/7.

So why did Roy choose this 18th-century image?

“I chose it because it’s a classic image of surveillance and surveillance by the state,” Roy said. And since Middlebury is an institution making choices about data privacy, he said, “We stand in for the state.”

According to the college handbook, Middlebury gathers institutional datasets on its people and programs. These datasets include financial, academic and health data on students; employment data on faculty; and philanthropic data on alumni and donors. Each dataset used by someone at Middlebury — by staff, by agents of Middlebury, or even by third parties who were granted access by the college — is overseen by a “data steward,” usually a department head.

These stewards determine how data are stored and accessed, and classify them as either public, internal or restricted. For restricted data, stewards are required to conduct regular security audits. Personal information like address, date of birth, Social Security Number, address, grades and transcripts are classed as restricted data.

Anyone who connects to the Middlebury wireless network is subject to routine surveillance. IT staff monitor server logs for malicious activity. In most circumstances, the information is confidential and not used to monitor individual activity.

But data acquired from network monitoring can be turned over to college officials and law enforcement in the event of an investigation. Access to that electronic information has to be authorized beforehand by a senior administrator. Only one of six people in President Patton’s cabinet can make this data request.

Roy said that some larger universities use institutional data to track student behavior.

“They will collect information about your movement around campus, through your ID card, your activity at the gym, your activity at the dining hall, coming into the library, using the course management system, using the course reserves. And if you have a large enough population, you can actually start to see trends.”

“There’s obviously this creepy Orwellian dimension to it,” Roy said. “We don’t, to my knowledge, have any interest in building such a system here.”

In Roy’s view, Middlebury has sufficient safeguards against that kind of data analysis.

“There’s a sense that there are stewards of particular records and that if you want access to those records you have to explain why you want access, what you’re going to do with it, how you’re going to protect it,” Roy said. “I definitely get a sense that there’s, broadly speaking, good governance about the use of data, therefore protecting against the misuse of it.”

In his memo, Roy said the policy aligned with Middlebury’s emphasis on “critical digital fluency,” which is aimed at understanding the role of technology in shaping daily life. As part of that, Roy said people on campus need to create norms about privacy and data, and think critically about what technologies they choose and how to configure them.

“We need to be clear with our community about what data we are collecting, how we are protecting it, who has access to it and how it is being used,” Roy said.

Davis Library Says No to Collecting Data on Patrons

Comments