DOMESTIC VIOLENCE FATALITY REVIEW COMMISSION

MONTPELIER — Firearm use and regulation crowd the headlines of local and national news sites as polarizing debates surrounding the demand for legal action continue. After the shooting in Parkland, Fla. that spurred hundreds of rallies across the country in February, the Vermont legislature was one of the state governments most attuned to the unrest.

After the thwarted school shooting plot by Fair Haven High School student Jack Sawyer, Vermont officials began to grasp how close to home unregulated guns can reach. Shortly after the Fair Haven attempt in April, Vermont became the first state to pass a law increasing the minimum age for gun purchases to 21. The legislature and Governor Phil Scott also passed laws to ban the use of bump stocks — which allow guns to fire nearly at the level of a fully automatic weapon — and expand background checks for gun purchasers.

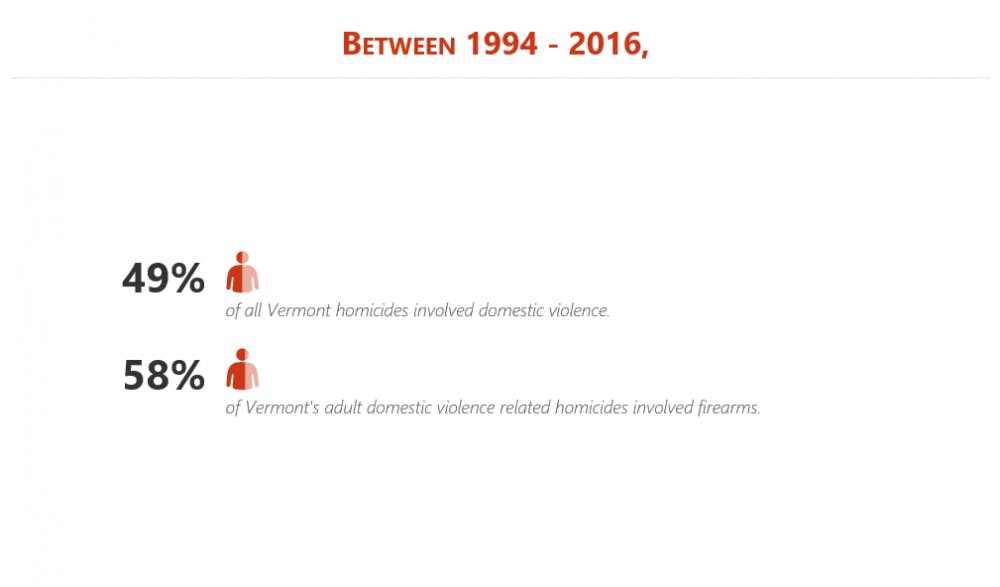

Lawmakers in the Green Mountain State have now turned their attention to another deadly combination — firearms and domestic abuse. According to the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence (NCADV), over 10 million women and men experience domestic abuse per year. Adding firearms to the equation, NCADV writes, increases homicidal risk by 500 percent.

In response to these statistics and the continued push for increased gun control, Vermont officials recently passed Act 92, which went into effect at the beginning of September.

The new law allows police officers to temporarily confiscate firearms from anyone who is cited or arrested on a domestic assault charge. This seizure is permitted given two conditions: first, the weapon is taken according to a search warrant and, second, the confiscation of the firearm occurs in order to protect the victim, their family members and/or the officer involved.

“[Act 92] takes the gun right out of their hands immediately,” said Avaloy Lanning, executive director of the Rutland domestic violence shelter NewStory, in an interview with VTDigger. “[Domestic abuse arrests] are times that an abuser or a perpetrator is going to feel the most threatened, and it may be the time they are most likely to use a weapon at their disposal.”

Vermont officials, in effect, are attempting to control one facet of domestic violence and create a more stable environment for those at risk of abuse.

Some Vermont lawmakers also see Act 92 as a practical legal step. “I think what it does is clean up and potentially standardize practices about how to go about this statewide,” said Rory Thibault, Washington County State’s Attorney, to VTDigger.

“What’s important with Act 92 is emphasizing the critical time period immediately after an alleged domestic violence incident, to promote safety, and likewise, ensuring there is a mechanism there to review those exigent removals [of firearms] when they occur.”

Thibault endorsed the new law in an effort to put a stop to domestic abuse while temporarily removing firearms from the hands of aggressors.

In theory, his perspectives complement the findings of the Vermont Attorney General’s Office — over half of the domestic violence homicides in 2016 were committed with firearms. Though the link between domestic violence and firearms is indisputable, Middlebury Chief of Police Thomas Hanley offered another perspective. While Hanley believes the law’s intentions are sound, he stated that its execution has structural flaws.

“If you serve an order on a person, [Act 92] doesn’t allow the police to go in and get the guns,” Hanley said. “It mandates the [aggressor] to turn them over to the police or a third party.”

Hanley expressed concern that this process is filled with uncertainty and is procedurally far too complex and time-consuming. “The third party is told that they are responsible for these guns and if they give them back to the [aggressor] then they are held in contempt,” he said. “[The third party] has to hold these guns securely. There’s no definition of what ‘securely’ is.”

While he is worried about the link between domestic violence and firearm usage, he believes Act 92 is heavily flawed. Because there is not appropriate gun registration, the aggressor may not even be giving the third party all of his or her gun supply. Without the ability to obtain a search warrant based on this order or the event, Hanley said, “if [the aggressor] is really intent on harming somebody, this law doesn’t [prevent] it.”

While skeptical of the new law, Hanley believes the relationship between domestic violence and firearms needs to be addressed. Similarly, Kerri Duquette-Hoffman of WomenSafe in Middlebury shares Hanley’s sentiment toward the often fatal link.

“My hope is that we will see more weapons removed at the scene of crimes,” said Duquette-Hoffman on what the implementation of the new law could mean for domestic abuse cases in Addison County. “The requirement that domestic assault charges must be arraigned the next business day may also prove to be an important tool for survivors.”

Lawmakers, police and organizers share her hope.

Although responses to the new law vary, most agree that Vermonters must provide increased support for domestic violence victims and create functional legislation that addresses the problem in a timely fashion.

“The presence of firearms in situations of gender-based violence is such a substantial concern for survivors and such a clear risk that we must take action to reduce it,” Duquette-Hoffman said.

Finding a middle ground between legal action, organizational involvement and community support will ensure a safer Vermont.

Guns: New Vt. Law Permits Seizure of Firearms from Suspected Abusers

Comments