For three days following the tragedy, the public did not know his name.

It was in the early morning of Saturday, Jan. 13, that Middlebury police found the body of a man who had frozen to death overnight off a path on the Town Green, covered with snow and sleet. The following Monday, local media began to report his identity: Suad Teocanin, a 45-year-old Middlebury resident who had been living at the Charter House during a recent period of homelessness. Following a night of drinking, Teocanin tried to make his way back to the Charter House before apparently collapsing, just yards from the shelter’s front door.

Reports of Teocanin’s death circulated around Middlebury that week, accompanied by photographs of his smiling face, descriptions of his recent homelessness and statements by police that alcohol had been a “significant factor” in his death. What these relatively brief media accounts could not capture, however, was the totality of Teocanin’s experience before his death — a life that began in the Bosnian city of Zvornik and led to ten years of employment at Middlebury College and another decade in the kitchens of several restaurants in town.

To the many people who knew him at the college and in town, Teocanin was not only a friend and coworker, but also a generous neighbor, a fellow immigrant and a bright spot amid the stresses of college life whose broad smile was cited without exception.

“The best antidote”

Teocanin came to America as a war refugee.

From 1992 to 1995, Bosnia was torn apart by ethnic conflict, as Serbian forces targeted the Muslim Bosniak population, burning cities and towns and massacring entire communities. In Teocanin’s hometown of Zvornik, tens of thousands of residents were driven from the area, and almost 4,000 were killed.

Teocanin was not Bosniak, however, but Romani, the historically itinerant ethnic group known colloquially as gypsies. Romani people, persecuted in Bosnia as they are in much of the world, were targeted specifically in the killings that took place in Zvornik. Those who knew Teocanin in Middlebury would recall that he rarely spoke about his life in Bosnia, or about the family he left behind. One former Proctor Dining Hall colleague, however, said Teocanin had spoken of witnessing the deaths of his parents and siblings.

Over 1,700 Bosnian refugees were resettled in Vermont between 1993 and 2004, and Teocanin was one of them. In Middlebury, a small community started to form by the mid-1990s, centered in the Pine Meadow Apartments near the Pulp Mill covered bridge. From their homes in the apartment complex that became known as Little Bosnia, Teocanin and his fellow refugees began to rebuild their lives in Vermont.

Jovanka Jandric was among the Bosnians who settled in Pine Meadow during that time, along with her husband, Refik, and their children. Refik came to the United States first in 1994, to a New Hampshire hospital, having lost both of his legs in Bosnia after stepping on a landmine. Jovanka came with their children several months later, and the family moved to Middlebury.

The older couple found jobs in town — Refik at Danforth Pewter, and Jovanka at the now-closed Greg’s Meat Market — and cared for Teocanin, who, in his early twenties, had arrived in town alone. “I loved him like a son. I’m old enough to be his mother,” Jovanka said. “He was too young.”

Refik (left) and Jovanka Jandric fled Bosnia with their children, and took care of Teocanin after settling in Middlebury.

Teocanin’s childhood education had been minimal and he never learned to read or write. In order to communicate with his brother, who fled to Germany, Teocanin brought his letters to Jovanka, who would read them and help him compose replies.

Teocanin, after a stint at Mister Up’s restaurant, found his way to the college, where he began work in 1998 as a pot washer in Proctor Dining Hall. His coworkers, several of whom remain at Proctor today, were struck by his ability to adapt in what must have been a daunting new environment.

“You always start out in a different place, not being sure of yourself,” said Claudette Latreille, who still works at the college. Colleagues watched Teocanin transform from an inexperienced new hire who spoke little English to a skilled worker who mastered the language and the intricacies of food service.

“He was the kind of guy who fit in by watching, and then doing what the cooks were doing and saying,” said Richard O’Donohue, now retired, who worked as Proctor’s head chef. Coworkers helped Teocanin study for a driving test, went with him to college hockey games and invited him to Middlebury Union High School to watch their children play sports.

A few years into his time at Proctor, Teocanin began to work in the main dining area known as the servery, and students began to gravitate toward his warmth and near-constant smile.

“College can be a little intense, and literally, Suad was the best antidote for that,” said Megan McElroy Rzezutko ’04, who formed a close bond with Teocanin at Proctor. She recalled the feeling of “being in the library for many hours and then seeing his smiling face, so elated to see you.”

Libby Pingpank ’04 remembered meeting Teocanin soon after her arrival on campus. “It was the first time we were away from home,” she said. “He was just this welcoming, friendly face that we always knew we would see when we went to eat.”

Teocanin became known for stopping by tables to chat and joke with students, and for his vast collection of movies on VHS tape that he offered up as gifts and even as betting payments, when a group of fellow employees began placing bets on football games.

“Suad had some money, but not a whole lot, and he’d make side bets,” O’Donohue said. “When he couldn’t pay the bet, he’d bring in a bag of VHSs. Everybody got to the point of, ‘No, Suad, we’re not doing VHS.’”

To employees like Dawn Boise, the current Proctor manager, memories of Teocanin’s socializing feel like symbols of a bygone era, when the smaller student population meant that staff could talk freely with students without the looming threat of the mealtime rush.

“You used to have a little down time, where you could chat with people,” she said. “Now, you really don’t have time to get to know a lot of the students, which is hard.”

For the students who knew Teocanin, memories of those conversations have only grown in value in the years since their graduation.

“Honestly, when I think back, it’s my advisor and Suad who had the most impact on my time in college,” McElroy Rzezutko said. “There’s obviously faculty and administrators there that are a part of your life, but this was different. It was comforting, and wasn’t forced.”

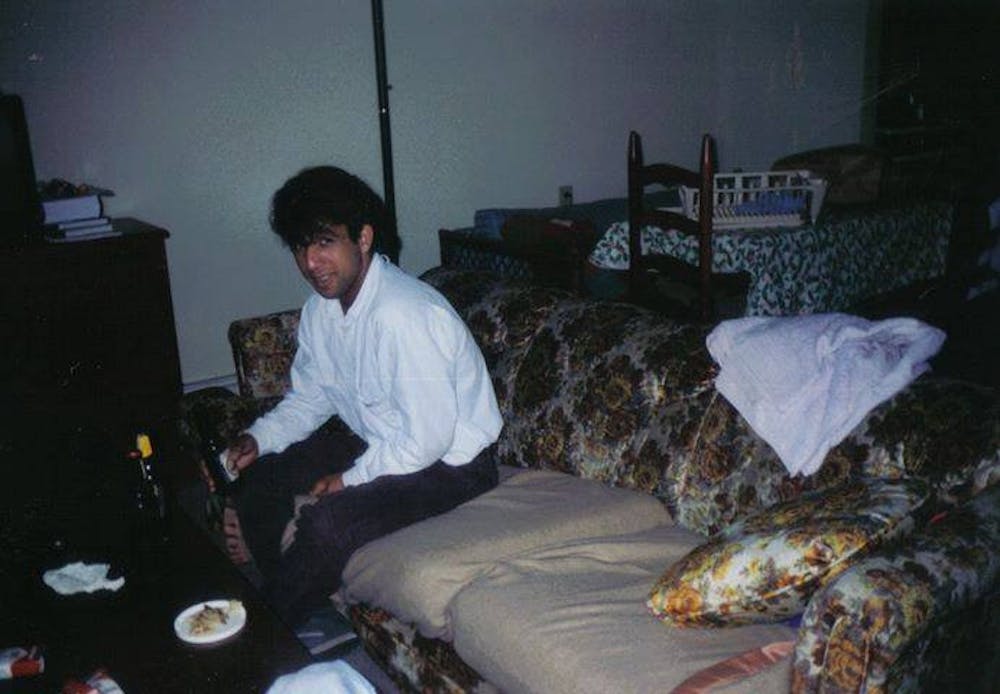

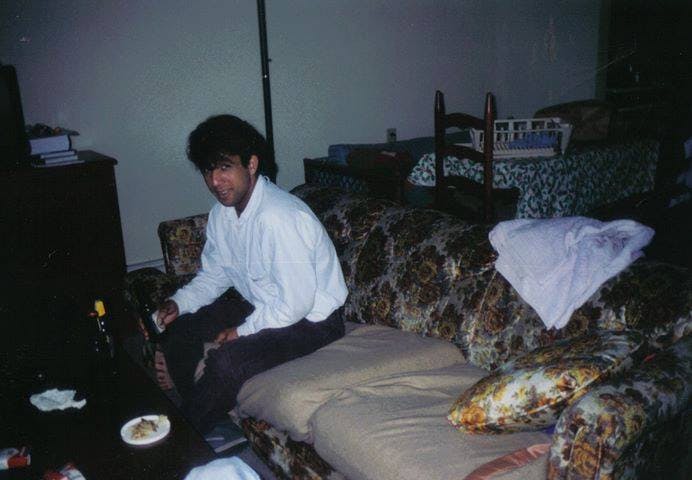

Teocanin, pictured in an undated photo, came to Middlebury in his early 20s. He remained here until his death.

“He was too good”

After over a decade, Teocanin left the college in 2010 after accepting a voluntary separation package offered by Middlebury following the 2008 financial crisis.

“When he decided to leave, we were pretty upset,” O’Donohue said. “But we couldn’t talk him out of it. He had his mind set.”

Years earlier, during his stint at Mister Up’s, Teocanin had worked alongside Megan Brady. When she and her husband Holmes Jacobs prepared to open Two Brothers Tavern, Brady insisted they hire Teocanin.

“He had a reputation of being a golden soul, a great person, a great work ethic and just a big heart,” Jacobs said.

Teocanin remained at Two Brothers until his death, working his way up from dishwashing to food preparation. There, like at the college, he became a beloved and visible figure, famed for his humor and, of course, his enormous grin. “Even though he had so many things stacked against him, he brought out the best in other people,” Jacobs said.

Work was steady, but Teocanin’s personal life was not. Over the years, the Bosnian community in Middlebury splintered along many of the same ethnic lines that had been present during wartime, and prejudices welled up against Teocanin’s Romani heritage.

“Not so many people liked gypsies,” Jovanka Jandric said. “Some people would open the door for him, some people would close the door.”

To make matters worse, friends say that a girlfriend extorted Teocanin out of what little money he had. Generous to a fault, Teocanin supported her unquestioningly. “Suad was one of those rare people who gave of himself to anyone without expecting anything in return,” Jacobs said.

For years, Teocanin had moved around frequently, often camping or living out of a truck when he had no reliable source of housing. As cold weather approached in the fall of 2017, Jacobs helped Teocanin move into Charter House.

“We’re so grateful for the Charter House,” Jacobs said. “But if he had been less generous with all of his time and money he probably would have had a housing setup that was more permanent.”

“He was too good,” Jovanka Jandric said. “Too naïve.”

“Richer and happier”

Jacobs remembers the day of January 12 vividly.

“It was a really weird, beautiful, sunny, 60-degree January day,” he said. “As the sun fell, the weather turned really quick.”

Temperatures that night dipped to 30 degrees and falling rain turned to snow. And Teocanin failed to make it home to the Charter House after a night of drinking in town.

The amount of alcohol that Teocanin had ingested came as a shock to those who knew him, as alcohol did not seem to play a major role in his life. News of Teocanin’s death left many in the community with the impression that he had long struggled with drinking, a notion that Jacobs feels compelled to refute.

“I don’t believe that he had a real substance abuse problem,” Jacobs said. “But that’s how he died, and that’s perhaps part of the perception that comes from that.”

In the days and weeks following his death, posts made on the Two Brothers Tavern Facebook page memorializing Teocanin garnered hundreds of reactions and dozens of comments.

“We have lost one of the biggest hearts we have ever known,” the first post read. “But deep down, somewhere hard to find tonight, we realize, as we always have, that each of us is so much richer and happier for having had Suad in our lives.”

However, months later, his friends still puzzle over the circumstances of his last night, and why Teocanin was in such a situation in the first place.

“It still confounds me a bit how he was left alone,” Jacobs said. “It’s unclear to me why the police weren’t called sooner to try to find Suad, especially when there had been witnesses to where he was. I feel like a phone call to the police could’ve saved him.”

Of all the ironies surrounding Teocanin’s death, including that he passed out just steps from shelter and that alcohol, a substance he seemed to use only rarely, was involved, what most disturbs those who knew him is the disjunction between the way he lived and the way he died.

“To me, the most horrific thing is that he was alone,” McElroy Rzezutko said. “This person that created such warmth, human-to-human.”

Amid their grief, James and Jacobs planned a memorial befitting Teocanin’s legacy at Middlebury’s Congregational Church. After first offering a small room, a church official eventually agreed to open up the entire building for the January 27 service.

Among the many attendees were Jandric, Jacobs and several Proctor employees. Speakers recounted how Teocanin made an impact on their lives in Middlebury.

“Everyone had a story, even if they didn’t really know Suad, about how he would help them cross the street, or [how] he would hold the door for them when he was walking into their shop with a big smile,” Jacobs said.

Since January, mementos of Teocanin have accumulated inside Two Brothers Tavern. A framed photograph hangs on the wall in the dining area, near the bar. Another sits above the sink, where Teocanin spent many hours washing dishes. And Jacobs is proudest of the life-sized poster of Teocanin, showing him beaming in his cook’s uniform, that now sits in the kitchen to greet Jacobs every day as he walks into work.

“It’s not Suad,” he said. “But it still makes me smile.”