In September 2015, the Environmental Protection Agency disclosed that the German automaker Volkswagen (VW) had installed devices in 11 million cars that cheated emissions testing, permitting their cars to emit hazardous nitrogen oxide. The reporting of Jack Ewing, Germany correspondent for the New York Times, led to Volkswagen paying a more than $20 billion settlement. Ewing’s 2017 book “Faster, Higher, Farther: The Volkswagen Scandal” digs deeper into the corporate scandal, tracing it back to the company’s history since the Nazi era and its top-down management culture.

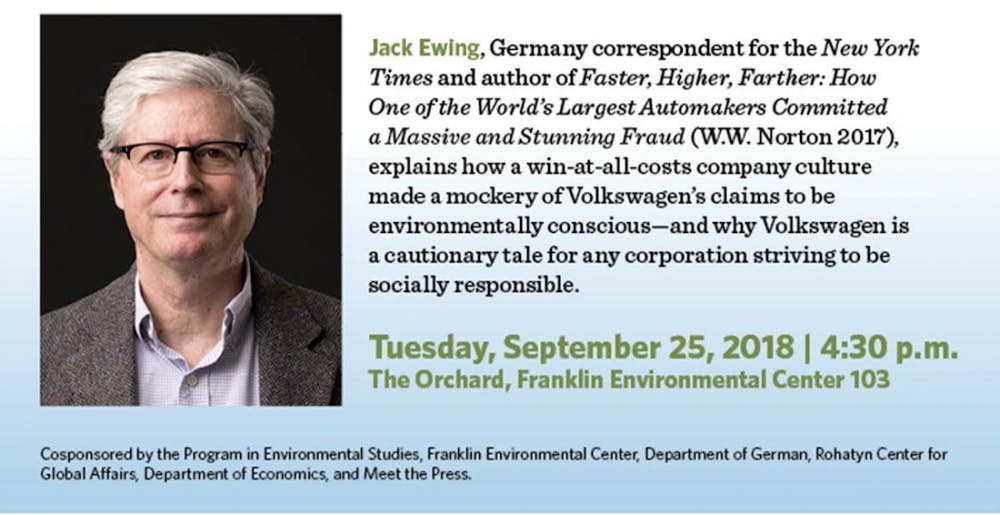

Ewing will discuss the topic this week in a lecture organized by the college's Environmental Studies program. His talk will take place on Tuesday, Sept. 25, at 4:30 p.m. in The Orchard, Franklin Environmental Center 103.

Last Friday, Ewing spoke with The Campus by phone about his book, lessons to be learned from the scandal and role of journalists covering the corporate world today. The interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

Yvette Shi (YS): When and how did you start to realize the role played by the company’s corporate culture?

Jack Ewing (JE): I had dealings with Volkswagen off and on for years, and I was already aware that it was a very kind of rigid, authoritarian type of company culture, and I knew who some of the leaders of the company were and sort of how they operated. So I think that was from the very beginning — not obvious — but I immediately had a feeling that the corporate culture certainly played a role.

And then we looked at the way the company responded to the scandal, and how close they were and how long it took them to confront it, to start investigating. And then when I started to develop sources inside the company or people that have worked at Volkswagen. At last, it just became clear pretty quickly that it was the kind of company where you couldn’t admit failure, you couldn’t say no to somebody above you and where there was not a strong moral underpinning or strong moral standard that people believe they are supposed to adhere to.

YS: Do you think that this sort of top-down culture is typical for large corporations?

JE: I think it’s certainly not uncommon. I think it exists to some degree almost in every big corporation. I think Volkswagen was the particularly extreme example, but at the same time I think it’s definitely the case that it’s something that can happen at any company. If you look at other scandals, like Enron, going back that’s been more than a decade, or Wells Fargo Bank in California, you know they were defrauding their clients on a massive scale, you always have this ingredient. The main ingredients are that you have a culture where people don’t feel they have any recourse when they are asked to do something unethical, and where you have top management setting extremely ambitious goals, and making it clear that if you fail, you are going to be fired.

So to that extent, and there’s lots of companies that operate that way, where they are constantly asking more and more employees and if you don’t deliver, your job is in danger. And that’s just an invitation for people to start to commit wrongdoing, because most people, even if they know that they can get caught in two years or five years, they’ll still try to hang on to their jobs for as long as they can.

YS: How do you think this kind of culture was formed in the first place?

JE: That’s a good question. I’m not sure I can totally answer that, but it definitely came from one person. The original Beetle was designed by Ferdinand Porsche for Adolf Hitler. Many years later, his grandson, who was named Ferdinand Piëch, in the early nineties became the chief executive of Volkswagen, which at that time was at its crisis. He turned around the company, but he himself was a very authoritarian figure. Brilliant engineer, but very, very hard on people and was very out-front about the fact when people don’t deliver, he’ll fire them.

So he was the one that really created that culture beginning in the nineties, and he was the chief executive for about a decade, and then he became chairman of the supervisory board, which is technically an oversight position, where you are overseeing the operational management. But he was still very involved and still the dominant person in the company up until just a couple months before the scandal became public. So it definitely came from him. To what extent it was already there, I’m not sure I’ve totally figured that out. That’s a hard thing to pin down.

YS: You talked about having sources inside the company. What was that process like? What were the challenges that you faced?

JE: That’s always difficult with a corporation. It’s particularly difficult with a company like Volkswagen. Volkswagen has over 300,000 employees. The first thing was to figure out the people we should concentrate on. What we did is that we found academic papers, where they have talked about their mission and technology, the engineers who have published papers in journals, and we found some papers that have names of engineers on them. Also we looked at patent registries that list the names of the people who get credit as inventors, and also helpfully their home addresses.

Then we just set about contacting those people. We did the usual thing, trying to call them a couple times, knocking on their doors — that wasn’t successful. I had the most success actually writing letters. So I would write people letters, tell them why I thought it would be in their interest to talk to me. I probably sent at least 50 [letters], and a much smaller number got back to me, but a number of people did get back to me who wanted to talk, and that was sort of the beginning where I was able to then figure out how the whole thing happened, the process with the whole illegal software being developed and then deployed over many years.

I guess the other thing was the lawsuits also had a fair amount of useful information. When the lawyers started filing lawsuits, they had some access to documents that I didn’t, which they then described in the lawsuits.

YS: What do you think motivated you when you were writing the book?

JE: The short answer is just that when the story broke, it’d been only about two weeks, and then the editor of Norton Books sent me an email saying “would you be interested in doing a book.” For a journalist, the chance to write a book is always a good thing. So I said yes, and we pretty quickly worked out a deal with the help of an agent. So the short answer is: I wrote the book because they asked me to write it.

But also, it was the topic that I just found very fascinating — it has so many aspects to it and it touches so many things, environment, corporate culture, technology. It’s an interesting cast of characters, interesting legal story. So I never got bored with the subject matter, I’m not sure “enjoy” is the word because writing is always hard, but it was a satisfying story to do. I never got bored with it.

YS: What can students interested in entering the corporate world after school can learn from the scandal?

JE: I think that you are going to learn a lot from the scandal. If you work in a corporation, there’s tremendous pressure to conform, people will possibly be asked to make moral compromises, and companies do not always help you to know when you are being asked to step over a line. I think that the clear message is that you have to maintain your own sense of what is right and wrong, independent of what your employer might be telling you. And if you feel that that’s being violated, you have to take action, you can’t just go along, you have to have moral courage.

I think that the people that were involved in this, a lot of them, their careers are ruined and in some cases they might go to jail. Also, a lot of them were fairly idealistic. They originally went into emissions technology because they wanted to make cleaner air, and then wound up being part of this fraud. So I think that the message is that you have to have the courage and the strength to stand up when you are being asked to do something like this.

One thing that I still find amazing is that at the very end there were a couple Volkswagen employees who went to the California regulators and said this is what’s really going on that’s wrong. But this is after they hid [the device] in cars for ten years. And the whole time, nobody went to authorities and said that there’s something really big illegal going on. Volkswagen would have been better off if they had. Everybody would have been better off. But nobody did that.

YS: And they are also now trying to have a whistleblower program in the company.

JE: Yeah, they have to — that’s part of the settlement with the United States. The question is whether it will be effective, because they had it on but it’s been a program where you’re supposed to be able to go for complaints, but nobody trusted it. People have to believe that if they blow the whistle that they will be listened to, that there will be action taken, that they and their career will not suffer. You have to be very careful the way you set these things up, so that they really do some good. There was just this case involving Goldman Sachs where somebody went to the whistleblower, but then instead of taking action, they went to somebody on the board and the person lost their job. That’s not the kind of whistleblower program you want to have if you are really sincere about preventing wrongdoing.

YS: What challenges do you think journalists today who are trying to cover the corporate world face?

JE: Corporations are rich, so they can hire a lot of people whose job is basically to keep you from finding things out. So that’s a constant challenge, and we are pretty much at permanent war with corporate PR industry. And people are afraid to talk to reporters. It’s hard to get beyond the PR department when you are trying to find out what’s going on, and that’s always one of the biggest challenges. At Volkswagen, you can do it but it takes a lot of work.

YS: What would you say is the role that a journalist should have there?

Traditionally I think that journalists were very focused on government and what government was doing right or wrong, but these days corporations have such influence on our lives, maybe even more influence than government — if you look at Facebook, Google — just how much they know about us and how much we depend on them. It’s really, really important to hold those companies accountable that takes a lot of resources, so I think that’s just an incredibly important thing for journalists at the moment.

YS: Is there anything else that you would like to add?

I guess the one thing that I always like to try to get across about this book is that some people think it’s a car book, and it’s not. I really tried to write it for people who don’t care about cars, don’t know about cars. My editor John Glusman, before we started working, he said: “Jack, you know, I really don’t care about cars at all.” And he doesn’t even know the difference between an automatic and a manual transmission. So he says: “You’re going to write a book that I’m gonna want to read.” So that’s really what I tried to do.

I sometimes hear from people, “I don’t really want to read a car book,” and what I always try to get across to people is that it’s not a car book, it’s about people and people’s weaknesses, ethics and bigger issues than just emissions.

Interview: NYT's Jack Ewing Talks Volkswagen Scandal, Upcoming Lecture

Comments