Vermont’s winter weather is often harsh and unpredictable, but this doesn’t stop farmers throughout the state and nation from braving the conditions to produce crops year-round.

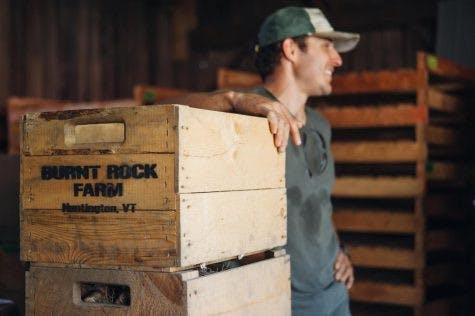

“We don’t ever stop producing,” said Justin Rich, owner of Burnt Rock Farm. Located in Huntington, Vt., Rich’s farm primarily produces storage crops, along with a few summer varieties. “We mostly grow potatoes, winter squash, sweet potatoes and onions,” Rich explained. “In the summertime, we grow some tomatoes and spinach as well.”

Burnt Rock Farm, which has been operating for nine years, began producing winter varieties out of necessity as Rich’s other commitments during the summer months left him with little growing time.

“When I started this farm, I was managing another farm, so I didn’t have much time,” Rich said. “I couldn’t go to farmers’ markets or start a CSA or anything, so I started growing storage crops, because I had more time in the winter.”

While Rich had no time to focus on a CSA (Community Supported Agriculture), Denver farmer Yosef Camire did exactly that. After moving to the outskirts of the city to raise his family on a homestead, an over-seeded vegetable garden paved the way for his organic CSA, now the largest in El Paso County.

“We basically made a farm that was too big for us, so we sold the extras and had a small, teeny CSA with about twelve members,” Camire said. “The response was overwhelming: the right place at the right time. So we doubled the year after that, and the year after that we doubled again and now we’ve doubled about four times since we’ve started, in 2014.”

In 2019, Camire plans on harvesting around 100,000 pounds of handcrafted food.

“This year, we’re going to grow around eighty different crop varieties,” he said. “We don’t use any tractors, we don’t till and we don’t use any chemicals or pesticides or anything synthetic. All we use is stuff we can make on the farm.”

Like Camire, farmer Will Stevens believes consumers are after a product that is produced locally and grown sustainably.

“It comes down to providing good-quality food for people at affordable prices,” Stevens said. As the co-founder of Golden Russet Farm, Stevens, like Camire, has seen his farm expand since its conception in the early 1980s.

“We started the farm because it seemed like it was a good thing to do,” Stevens said. “It seemed as if there was a need for this type of thing and we wanted to be a part of it. It was pretty serendipitous, really — we were given the opportunity to grow some vegetables on a neighbor’s property and sell things at the Burlington Farmers’ Market, and it just grew from there.”

Though Golden Russet Farm does not produce winter crops, the winter months remain a busy time for Stevens and his family.

“Right now, my wife and daughter are sitting down, coming up with the plans for the cut flower production,” Stevens said. “That includes ordering seeds, spacing, deciding where we’re going to plant things, what dates we’re going to plant them, et cetera. We do a lot of work in January so we can easily implement what we’re going to grow later in the year.”

In addition to planning the upcoming season, Stevens allocates a portion of his winter to the business side of his farm. “We also spend a lot of time tying up the book work from the previous season, doing all the tax filings, reporting and the maintenance stuff that didn’t get done during the growing season,” he said.

Rich, whose growing season continues into the winter, attested to doing much of the same during winter months. “I spend all my time at my desk in the wintertime, ordering and crop planning and bookkeeping,” Rich said.

In addition to winter activities akin to Stevens’, Rich keeps busy with the growth and harvest of winter crops. “In the wintertime it’s all cold weather crops,” Rich explained. “Growing is way different. It’s much more difficult. You have shorter days, so you have less time to work, and in the morning and afternoon you have opening and closing procedures which take an hour and a half to two hours both in the morning and in the afternoon.”

Justin Rich, owner of Burnt Rock Farm, rests against produce crates.

Camire also commiserated with the difficulty of growing winter crops, which he does without the use of a greenhouse. “Diseases are more prominent in winter,” Camire said. “You can’t reseed, and if you do, you won’t get anything for six months. The timing has to be perfect: the crops have to be three quarters mature by the time Nov. 15 comes around, which is the ten-hour day. Nov. 13 was our ten-hour day. You have to make sure your crops are three-quarters grown by then because they keep growing throughout the winter, but very, very slowly, and it all depends on the winter.”

To add to the hostility of winter growing, Camire’s refusal to use greenhouse technology has made farming during Colorado’s winter months a gamble. “This year we are having a very cold winter. It’s the coldest on record, so our selection really stinks,” he said. “We’ve lost some crops.”

These risks are foreign to Dave Hartshorn, co-owner of Green Mountain Harvest Hydroponics, a greenhouse situated on Hartshorn’s organic farm in Waitsfield, Vt. “In the hydroponic, we have a protected environment where we can grow anything we want in the winters of Vermont,” Hartshorn said.

Hartshorn realizes that the greenhouse is particularly helpful in a place with rapid weather fluctuation. “Last week, we were fifteen below, yesterday we were fifty above, and tomorrow we’ll be back below zero. In the summer we are in the nineties a lot,” he said. “Because of recent new technologies, however, anything can be grown in Vermont because we have the ability to create any environment in the world in a greenhouse setting.”

While Hartshorn’s winter harvest of basil and watercress is wildly different from Stevens’ off-season winters, Rich’s storage crop production and Camire’s homestead all four men share the lessons farming has taught them.

“From a learning perspective, agriculture has a lot to offer,” Stevens said. “If you take a systems approach, you’re taking a seed and putting it in the ground and nurturing it and turning it into something that’s useful. That’s powerful. When folks come to work here, they get a lot of life lessons from experiencing what it takes to get from a little seed to a case full of a product that is going to be enjoyed by people.”

Hartshorn agreed: “Farming is everything. It’s math, science, chemistry, research, social interaction with people, marketing, financial, everything you can think of that you can incorporate into one occupation.”

Ariadne Will ’22 is a local editor for the Campus.

She has previously served as a staff writer, where she covered topics ranging from Middlebury’s Town Meeting to the College’s dance performances.

Will also works for her hometown newspaper, the Daily Sitka Sentinel, where she covers tourism and the Sitka Planning Commission.

She is studying English and American literature with a minor in gender, sexuality and feminist studies.