Columbus Day may soon become Indigenous Peoples’ Day in Vermont, thanks to a bill (S.68) passed by the Senate on April 17. The bill was met with resounding approval, and will become a permanent change once it receives Gov. Phil Scott’s signature.

For several years, Scott has signed the executive proclamation changing the holiday’s name, just for the day. Former Gov. Peter Shumlin also supported the measure from 2016 to 2018. This year’s legislative action, however, will enforce the change as state law.

Several other states are in the process of renaming Columbus Day to Indigenous Peoples’ Day, including Alaska, South Dakota, Oregon, Minnesota and Hawaii. New Mexico and Maine recently established the switch in official state law. Among cities and towns, popular opinion is leading to similar change on a local scale.

John Moody, an active member of the Abenaki community in Hartford, Vermont, noted the amount of support from the state government and residents in renaming the holiday.

“This came from the governor’s office and general consensus. The Hartford town vote was 55 percent to 45 percent in favor,” Moody said. “The process in town was remarkably civil and quiet considering the continued carnage in nearby New Hampshire over the same issue,” Moody said, citing the fact that at least half of Hartford’s population identifies as Native American as a possible reason for this civility.

Led by Republican Governor Chris Sununu, New Hampshire’s Senate rejected the bill. Although the vote was a success in Vermont, there was a fair amount of opposition from 24 Vermont Republicans, who voted against the change.

Republican representative Scott Beck believes Indigenous Peoples’ Day should be celebrated as a separate holiday. “Columbus is one of the great discoverers of all time. He is what really led Europeans over here, he was a big part of that,” Beck commented in an interview with VTDigger.

According to Middlebury College American Studies Professor William Hart, however, changing the name of a holiday, building or landmark doesn’t affect the underlying history. Instead, it dismantles the European narrative, addressing repressed elements of history.

While changing the name of the holiday can’t change the “five-hundred-year history of disease, enslavement, displacement and conquest,” explained Hart, what it can do is “de-center the story; it takes away from reaffirming Columbus as the [only] history in the Americans and in the West.”

Columbus Day was initially observed with church, festivals and feasts before becoming a national calendar holiday in 1937 and currently represents a symbol of American national identity for some. However, what Columbus Day fails to address is how, for the first 200 years of early U.S. history, European settlers were not only the minority among those Native peoples already living there — but the European settlers were also guilty of mass genocide and colonization of those peoples.

“Our governing institutions, Constitution and principles of liberty come from Great Britain, so that is the link that Americans make to their past and to their heritage,” Hart said. “That is the story that gets amplified and centered in this pageant of American history. Changing Columbus Day to Native Peoples’ Day or Indigenous Peoples’ Day is a way of embarking on this vast early American perspective.”

According to Hart, making this change would contribute to a de-centering of Europeans and a re-centering of Native peoples, forcing us to consider who lived here and “made this history possible.”

“Enslaved Africans play a central role in this America as well. Without enslaved labour, this nation would not have been able to build itself as it did from 1600 to 1790,” he said.

By reframing the historical narrative, this change contributes to a movement among early American scholars, who are shifting their ways of teaching and understanding American history. The change helps bring non-Europeans to the forefront of American Studies, so that they are no longer an alternative topic, tangential to the European narrative.

“I think curriculum changes are already beginning here at Middlebury; you see lots of changes that address the diversity of the U.S. culture, literally, historically, and so forth,” he said, bringing the broader cultural shift in education to a more local context.

“Now it’s changing,” Moody said. According to Moody, people with indigenous blood are engaging with their Native American heritage and connecting across societies. “Vermont seems like the whitest state in the union,” he said. “But there’s a tremendous amount of people with native blood.”

A Signature Away From Permanent Change to Indigenous People’s Day

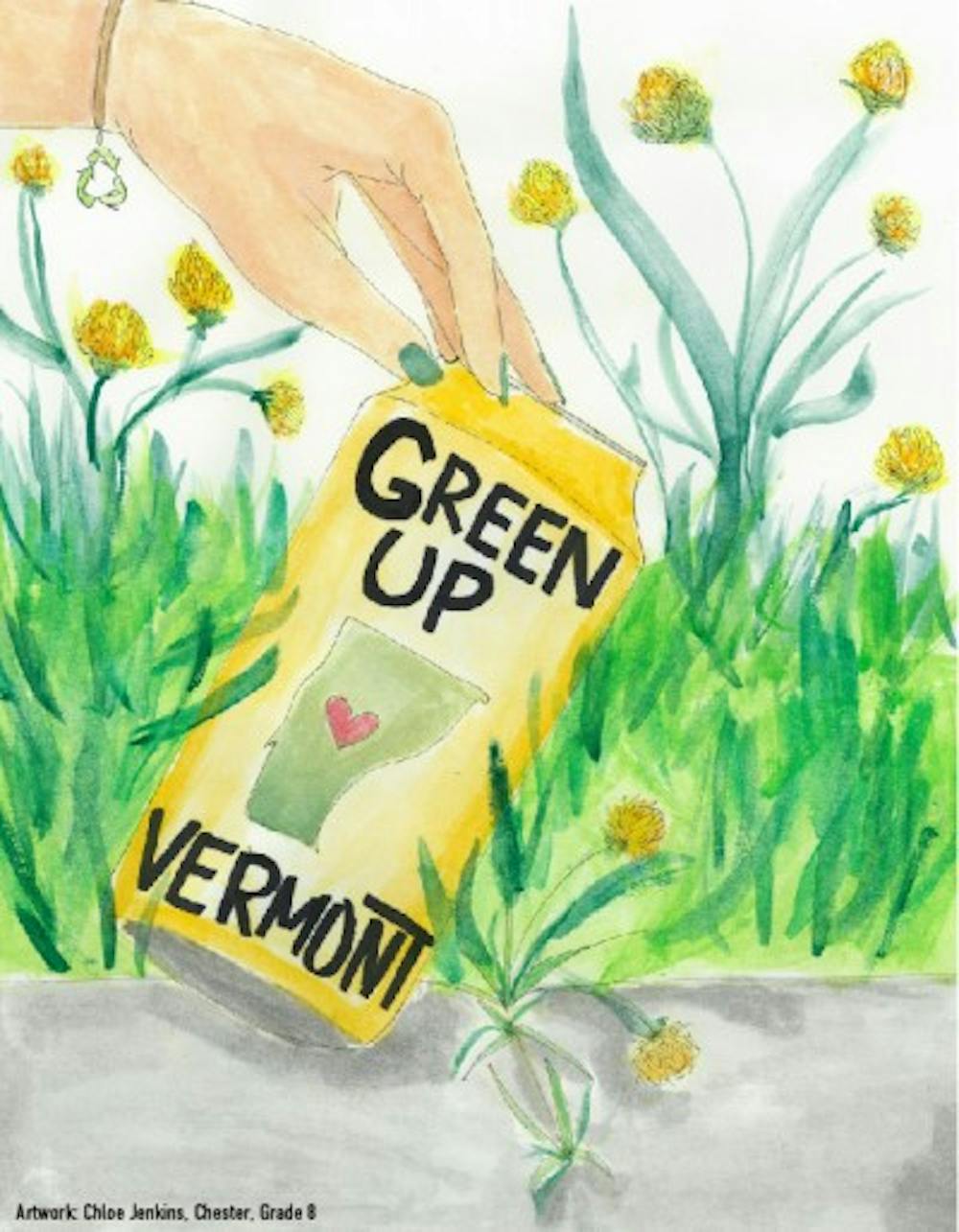

Green Up Vermont

Artwork by Chloe Jenkins, Grade 8 of Chester, VT, winner of the Green Up Day 2019 Poster Design Contest.

Artwork by Chloe Jenkins, Grade 8 of Chester, VT, winner of the Green Up Day 2019 Poster Design Contest.

Comments