Many students struggle with mental health during their time at college. At Middlebury, receiving mental health support can be an obstacle in itself.

Over the course of a three-month investigation by The Campus, students voiced frustrations with aspects of the college’s mental health services ranging from difficulty scheduling counseling appointments to a lack of specialized care for issues like alcoholism and eating disorders.

At Parton’s Counseling Center, for example, students can sign up for counseling sessions up to two weeks prior to their desired appointment. But demand for Parton’s counselors has surged, and students are hardly ever able to schedule appointments less than two weeks in advance.

“On the online portal you can only sign up for two weeks in advance, but if you’re not on the dot on the day that those two weeks open up, you’re not going to get anything,” said Angie McCarthy ’19, who has used Parton counseling in the past.

College campuses nationwide are facing the challenge of providing services to a generation of students seeking mental health support in greater numbers than ever before. Between 2009 and 2015, the number of student visits to college counseling centers increased by an average of 30% nationwide, according to a 2015 report by the Center for Collegiate Mental Health. Evolving cultural standards have lifted some of the stigma around discussing mental health, and colleges are scrambling to provide enough counselors, focus groups and hotlines for the growing number of students seeking help. Colleges are becoming more competitive, too, suggesting an uptick in student stress levels.

According to Gus Jordan, Parton’s executive director of health and counseling services, Middlebury is no different: Students in 2019 are requesting appointments with Parton counselors at higher rates than ever.

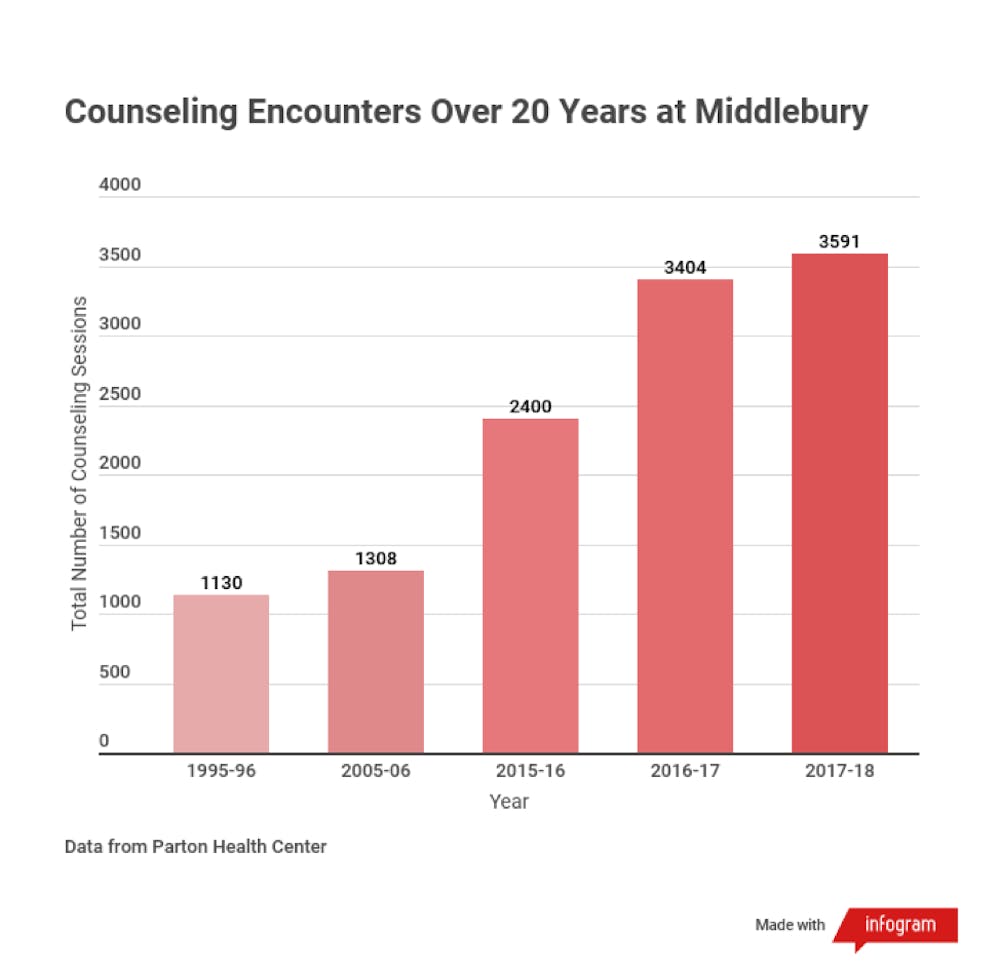

Over the past 25 years, Parton tried to meet growing demand by hiring more counselors, with its counseling staff increasing five-fold during that period. Parton now employs seven counselors and three interns, compared to two counselors in 1995. The counseling center held just under 3,600 counseling sessions during the 2017-2018 school year — compared to 1,130 during the 1995-1996 school year, according to data provided by Jordan. Still, though, demand has outpaced availability of late.

“The number of students requesting counseling appointments has skyrocketed over the last five years,” Jordan said.

Scheduling dilemmas

The rise in requests has contributed to droves of students going to Parton to schedule time with a counselor, only to be met with sometimes excruciatingly long waiting periods. Peter Lawrence ’21, who has used Parton’s counseling service in the past, became frustrated with waiting periods during which he says his mental health worsened.

“I could never seem to see a counselor two weeks in a row,” Lawrence said. “It was bad because I’d have a week and have a productive conversation, then I wouldn’t be able to follow it up for a week or two. Often, during those two or three week periods I would really struggle.”

When students experience particularly low moments, it can be discouraging to head to Parton’s online scheduling portal and see a two-week wait period before counseling appointments are available. These waiting periods can make it feel as though students have to “schedule” mental health episodes, McCarthy said.

“Whenever I started having flare-ups, it’s like, wow, I really need to talk to someone about this right now, but there’s no availability right now,” McCarthy said. “Even if you email and ask for an emergency slot, they kind of make you question whether or not you’re having an emergency.”

Emergency counseling slots can be scheduled for students in dire need of help so that those students can then bypass long waiting times. As evidenced by McCarthy’s experience, though, students’ definition of what constitutes a “crisis” doesn’t always line up with Parton’s.

“I’m not really the type of person to reach out unless I think something really bad is happening,” McCarthy said of the emergency counseling service. “One more person being like, ‘Is this real?’ is an incredibly disheartening response to a request for help.”

According to Jordan, students can see Parton counselors for emergency counseling sessions, available via email or phone request, when they are determined to be at risk of self-harm or are experiencing “significant crisis,” such as death of a family member, sexual violence or harassment. If a dean or CRD expresses immediate concern for a student’s well-being, Parton “works very hard to get the student in quickly,” Jordan said.

Specialized help

Students’ frustrations with the college’s mental health resources go beyond scheduling and availability. Over the course of The Campus’ reporting, students expressed frustration at the lack of care for specific health issues that intertwine closely with mental health.

Substance use is one. A student, who asked to be referred to as John, sought counseling after a period of struggle with alcohol abuse and became frustrated at the lack of specialized attention given to alcohol and drug use within the counseling department. The Campus granted John anonymity because of the sensitive nature of his story and its relationship to drugs and alcohol.

“The fact that they don’t have a drug and alcohol counselor here for students who are clearly overusing, or improperly using, is a shame,” John said. “College drinking habits determine how you’re going to drink for the rest of your life, because that’s when you start to form a certain relationship with alcohol. Having a specialized counselor to help with that would be hugely helpful.”

John was happy with the positive relationship he was able to develop with his counselor, though he said he did experience frustrations with scheduling felt by McCarthy and Lawrence. What continued to bother him was the lack of specialized knowledge his counselor had about substance abuse.

Staff in the office of Health and Wellness Education and some commons deans are trained to deal with substance use issues, but that doesn’t always feel like enough, John said. When alcohol use becomes harmful in the way that it did for him, John said, having a trained expert could be of tremendous help to students.

Though John recognized that hiring a specialized drug and alcohol counselor would pose a financial burden for the college, he said that not doing so ignores the realities of substance use on campus.

“I don’t think this is something malicious or someone trying to save money by not hiring a drug and alcohol counselor, but I think it is a lack of being in tune with the student body,” he said. “The college has people in the commons who are meant to punish you if you overuse drugs and alcohol. In that way, they very much know what’s going on. The difference is they’re choosing not to treat the underlying causes of these things.”

Hiring a specialized drugs and alcohol counselor is not common practice for college mental health programs. Counseling centers like Parton’s instead seek to hire counselors who can address an array of different mental health issues, Jordan said, because counselors must be versatile given the number of students they meet with and issues they confront.

“What we try to do is have staff who are well-enough trained to manage a variety of issues that come in,” Jordan said.

Student support groups

This fall, Parton will work with the office of Health and Wellness to improve care through new support groups, online resources and a new focus on alcohol and drug-related issues.

Students feel the need for more specialized care in more areas than just substance abuse, however. Henna Vohra and Amanda Werner, both ’21, work with the student group Every Body, which provides support to students struggling with eating disorders. Like John, Vohra and Werner feel that the administration has largely ignored the prevalence of an issue that plays a huge role in Middlebury students’ mental health.

“The purpose of this club is to get people to talk about eating disorders because it’s an issue that gets pushed under the rug,” Werner said.

Many students end up coming to Every Body for a level of support that might be better suited to a professional, according to Vohra. Students often come to meetings with medical and psychological questions that exceed the expertise of student organizers.

“We’re just a group of students, and we really wish we could help with those types of questions,” Vohra said. “But the fact that students have to dig through all available resources and all they could come up with was reaching out to us is really telling of how hard it can be to get help.”

Werner and Vohra said that students seeking help with an eating disorder can explore off-campus options with Parton’s direction — but that opens a new set of questions about access (geography and insurance coverage pose challenges to students), as well as the college’s responsibility to provide students care.

“I think that at the point that the campus needs to tell the student, ‘We don’t have these resources here and therefore we’re going to put you off campus to find these resources,’ that’s when we need to wake up,” Werner said. “We need to realize these on-campus resources are not enough. We need to improve.”

Solutions

Parton hired a new counselor this past spring. According to Jordan, the newly-hired counselor’s schedule was booked solid almost immediately. Counselors are an important part of any college’s mental health resources, but they cannot address the growing demand for student mental health services on their own.

“Even if we added three more full-time counselors, I’m not confident that that would solve our problems,” he said. “I think that within a month, all of them would be full. We have to think systemically, across the campus for multiple ways of supporting students in these situations.”

Instead of relying solely on counseling going forward, Parton and the Office of Health and Wellness are turning to what Jordan terms “creative solutions” to address concerns of students like John, McCarthy and others. Through improved training for students and Res Life staff, Jordan hopes that students will be able to get help from peers, CRDs and deans — people who live and work in close proximity to them — before they reach a level of “crisis.”

This fall, Parton will work with the office of Health and Wellness to improve care options across three areas. First, Parton is seeking to organize peer-and-counselor-coordinated support groups for issues like anxiety and academic stress. Second, Jordan is hoping to make online resources — phone apps and cognitive behavior therapy online software programs — more widely available to students. Third, the office of Health and Wellness will expand staffing, including new staff focused on alcohol and drug-related issues.

Parton will also work with the JED Foundation, a public health organization that seeks to provide access to mental health services, to improve care options this fall.

“I think that if we engage in a couple of years of increased training around mental health issues for what lay-people can do to help each other, that will help our campus broadly,” Jordan said. “So that student, staff and faculty feel empowered to support a person who is struggling, that might be enough. Then, if it’s not enough, to refer that person into counseling.”

Wonnacott Commons Dean Matt Longman, a member of a campus-wide residential staff that works in close communication with Parton to provide students mental health services, sees it as a good sign that students are seeking out help more actively than in years past.

“I’ve witnessed a trend in students contacting the college in advance of their start at Middlebury to ensure that a connection will be made in accessing counseling support services,” Longman said. “This reflects that many incoming students are entering college with an awareness of what their needs for support will be at Middlebury.”

It’s important to note that not all students arrive on campus knowing how to ask for help with mental health issues, Longman said. Additionally, he said, the increase in students asking for help is likely the product of more than just heightened awareness; increases in anxiety, depression and other mental health challenges likely correlate to Middlebury’s rise as a competitive and high-achieving institution in recent years.

Whether the increase in desire for mental health support is the product of decreased stigma or heightened campus competitiveness — or some middle ground between the two — access to support continues to serve an important purpose in helping students succeed in environments like Middlebury’s. For students who come to Middlebury from high school or family backgrounds in which mental healthcare was unavailable, seeing a counselor for the first time can be a transformational experience.

“The first time I went to Parton and talked about a bunch of issues I’d had in my home life was the first time I’d had an adult say, ‘wow, that’s messed up,’” McCarthy said. “I was a scared 18 year old and I was thinking, why can’t I deal with these things in a way that makes sense to me? Having someone outside of my family, outside of my peer group, say ‘it’s okay that you’re feeling this way because of what has happened to you’ was incredibly affirming, and that’s really what I needed out of that time.”

College Struggles to Meet Surging Demand for Mental Health Support

MICHAEL BORENSTEIN/THE MIDDLEBURY CAMPUS

Comments