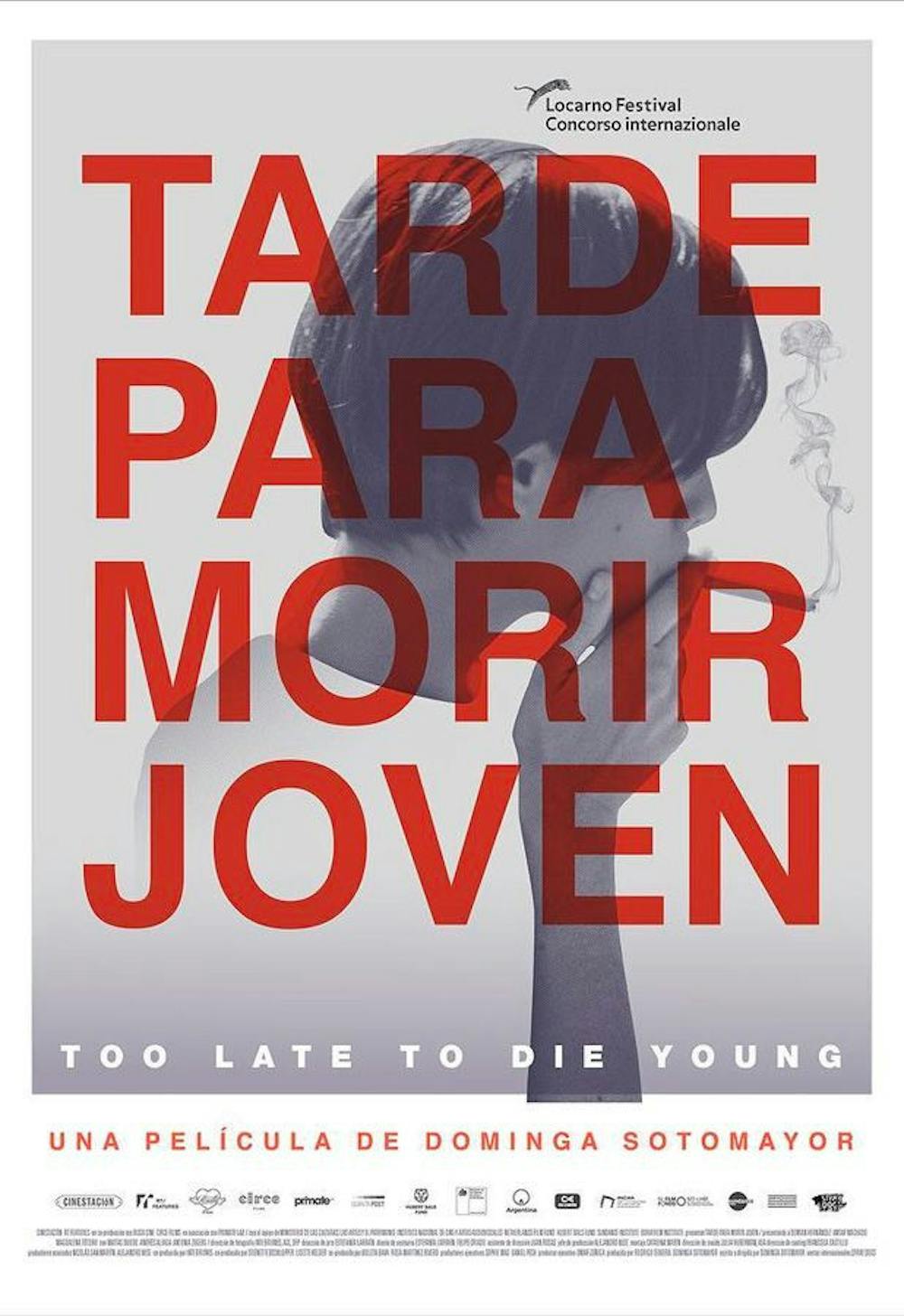

Imagine a collection of rivers running parallel to one another, never touching but ultimately flowing into the same ocean. This is the sort of storytelling that comes to life in Dominga Sotomayor’s feature, “Tarde Para Morir Joven” (“Too Late to Die Young”). From the very beginning, we’re given a string to follow when Frida, the neighborhood dog, gallops away from her owner in a hypnotic travelling shot. The film comes back into focus on the rest of the characters and their own unraveling narratives as they prepare for the New Year’s party, where their stories eventually reconcile.

The film is set in the summer of 1990, in a newly democratic Chile shortly after the fall of the dictatorship. The nation, young and temperamental, mirrors the 16-year-old lead, Sofía. Categorically, this film would fall into a coming-of-age story, but it does much more than that. It follows not only Sofía, but the rest of the rural, sun-drenched community, offering snapshots of small and intimate moments. The village itself is gorgeous and idyllic,in way that makes you want to pack your bags and book the next flight out — if you’ve seen “Call Me by Your Name,” you’ll know what I’m talking about (they have the same producer). Sotomayor’s style captures everything and nothing all at once — it’s a film that has to be felt rather than analyzed. It is a wholly immersive experience.

Despite the seemingly utopian setting, Sofía finds herself struggling with imminent adulthood. This peeks through in the way she defends her smoking habit. In a particularly amusing shot Sofía tells her dad it’s too late, she’s already a smoker, and he needs to get over it. Rather than joining her friends in preparation for the New Year’s Party, Sofía is constantly seen on her own in a typical daze of teenage angst. Her character and her struggles don’t seem to fit within the frame of her bohemian community, and she longs to move to the city. Amidst her turmoil, Ignacio, who is older and embodies everything that draws Sofía to the city, returns to the village. His arrival unnerves her childhood best friend Lucas, evident from his myriad glares and awkward silences.

Streaming alongside this is another story. Sofía’s neighbor, a 10-year-old named Clara who loses her dog Frida at the start of the film, searches tirelessly for her best friend. After weeks of stapling posters and mournful glances, Clara finds a dog who looks just like Frida living with another family in the city. In a breath of hope, Clara brings the dog back just to realize she’s not Frida after all. In the final shot of the movie — and in the same style as the very beginning — we see Clara’s new companion bounding away in a cloud of dust.

In all of its sweeping observations, the film never seems to land on any particular aspect or continuous storyline. Each individual struggle feels as if it flows alongside the other, twisting and curving, but never overlapping until the night of the long-awaited party. Even then, we only see the combined frustration and tension of the characters without being told how it can be resolved.

There is a beautiful moment when Sofía gets up to sing “Eternal Flame” for the party, and she sees Ignacio in the crowd. In that moment, it’s hard to tell the difference between Sofía’s feelings and your own; it’s something universal.

Neither Sofía’s, Clara’s nor Lucas’s struggles ever reach a breaking point, they’re all just “there.” Over and over, the film edges on raw emotion, but as soon as it comes close to any point of resolution, it pulls away and zooms into another detail of the jigsaw puzzle-like narrative. It’s an “almost, almost, not quite” feeling — leaving you entranced but not satisfied.

Reel Critic: ‘Too Late to Die Young’

STORYBOARD MEDIA

Comments