Minimalism, exposed elements, utility — the Bauhaus may not suffer from lack of fame or name recognition, but how much do we know about the people behind the movement?

On Wednesday, Sept. 11, Dr. Elizabeth Otto, Professor of Art History and Visual Studies at the State University of New York at Buffalo, presented excerpts from her forthcoming book, “Haunted Bauhaus: Occult, Spirituality, Queer Identities, and Radical Politics,” to a packed classroom on the ground floor of the Mahaney Arts Center. After a brief introduction by Erin Sassin, assistant professor of History of Art & Architecture, Otto began her lecture, titled “Queer Bauhaus,” with a background of the influential art school and the period during which it existed, the Germany’s Weimar Republic (1919–1933).

Otto described how the school was committed to the free expression of ideas despite the constraints of German society at the time. The Bauhaus made the bold decision to close itself rather than to cave in the face of Nazi demands to create propaganda for their party. Despite closing its physical doors, the ideas and techniques of the Bauhaus continued to spread throughout the world, inspiring a generation of painters, sculptors, craftspeople, architects and other artists.

Before beginning her queering of the Bauhaus, Otto mentioned that the Bauhaus was unique because it was one of the first schools to encourage students to “do their own thing” instead of emulating the masters. Otto is working to reintegrate women — who comprised 38% of the membership of the Bauhaus — and queer people into the memory of the institution.

Despite occurring during the first week of the fall semester, participants far exceeded the capacity of the classroom in which the lecture took place. Cara Levine ’20 said, “This lecture expanded my understanding of the Bauhaus in terms of its artistic reach as well as its philosophical vision. It brought queerness, something important to me, to a movement I have always adored.”

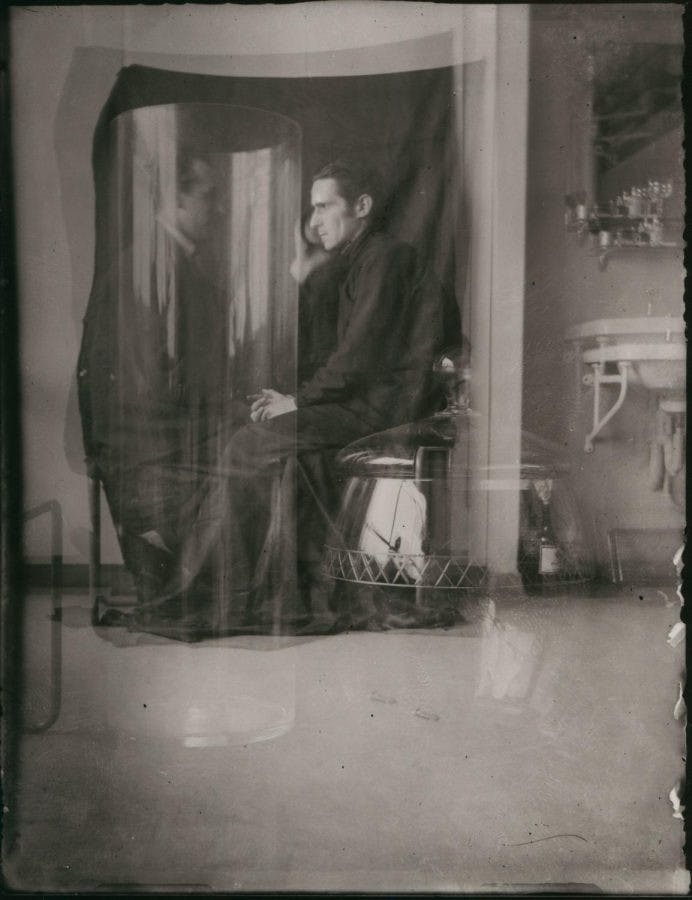

“Doppelportrait Heinz Loew und Hermann Trinkaus im Atelier” is a double-exposed photograph that layers two photos in one, resulting in what is sometimes called a “ghost photograph.”

Otto then displayed several photographs from the Bauhaus that displayed what she deemed a “queer sensibility.” One of these, “Doppelportrait Heinz Loew und Hermann Trinkaus im Atelier” (Double Portrait of Heinz Loew and Hermann Trinkaus in the Studio), depicted two men dressed in loose black suits, facing each other. One man has placed his hand on the cheek of the other and appears behind a translucent glass cylinder that completely covers his body.

Quoting the oft-repeated statement from the sodomy and gross indecency trial of Oscar Wilde, Otto said that the men of the portrait are “haunted by the love that dare that speak its name.” The men don dark apparel in front of a dark background, resulting in ambiguous silhouettes, thus allowing for plausible deniability of the relationship between the two men.

After taking the audience members through several other Bauhaus works and analyzing their queer representations, Otto concluded her lecture by discussing the significance and limitations of her research. Specifically, Otto pointed out that queer individuals had been erased from the history of the Bauhaus, and she is working to reincorporate their lives and memories into the public memory of the school. While LGBTQ+ members of the Bauhaus took significant risks to express their identities due to homosexuality’s illegal status in the Weimar Republic, they are not present in survey textbooks nor in blockbuster exhibitions. Otto’s personal challenges to completing this project include the ongoing restoration of the Bauhaus Museum in Dessau, especially as many research materials are in storage and inaccessible.

The Bauhaus served as a beacon for queer people around the world. It was a place where individuals were encouraged to express themselves and live freely. With continuing research into the influences that queer people had on the Bauhaus and the Modernist movement, these revolutionary artists’ stories are finally being told.

Bauhaus: they were here (in Weimar Germany) and they were queer

COURTESY OF MOMA

Comments