“There will never be a new world order until women are a part of it.”

These are the words of Alice Paul, an activist who fought for ratification of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which declared that the right to vote shall not be denied on the basis of sex.

As we celebrate the 100th anniversary of that amendment, we ought to remember the people and organizations that worked to make this important milestone possible. That is the message behind Middlebury’s latest museum exhibit, “Votes… for women?”, which opened Sept. 13. Curated by History Professor Amy Morsman, the exhibit acknowledges the remarkable contributions of those involved in the push for women’s suffrage while also examining their words and actions through a critical lens.

The exhibit was partly inspired by the work of my first-year seminar, “The Woman Question.” Taught by Professor Morsman, the class explored the changing roles of women in the U.S. in the years prior to 1919, when women were relegated to housework and removed from the public sphere.

The exhibit begins with the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848, organised by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott. At the historic convention, delegates drafted the “Declaration of Sentiments,” a manifesto demanding gender equality. Resembling the 1776 Declaration of Independence in its language, the document insisted on the equality of men and women and their fundamental rights of “Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.” Among its resolutions was a call for suffrage, for which Stanton and Mott became subjects of ridicule in the press at the time.

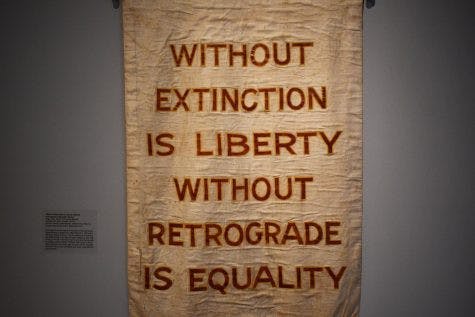

A banner featured in the exhibit inspired by Walt Whitman’s 1856 poem “By A Blue Ontario’s Shore.”

A theme of the exhibit is that suffragists struggled with internal politics. They were divided over the 15th Amendment, which was passed in 1870 and prohibited voting discrimination only on the basis of race. This division led to the creation of two separate groups, the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) and the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). The NWSA sought enfranchisement through a federal amendment, whereas the AWSA took a state-by-state campaign strategy. The two groups later merged into the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) in 1890, which decided on the state-by-state approach.

The National Women’s Party (NWP), another suffrage group, emerged during the 1910s. It was founded by Alice Paul, who had prior experience leading suffrage campaigns in England. She brought this experience to the U.S. and organised protests in Washington D.C. for federal suffrage legislation. The exhibit shows original banners that NWP members held while picketing in front of the White House, as well as images of these pickets.

The exhibit critically explores the intersection of women’s suffrage, racial justice and economic status and states that the suffrage movement was divisive at its core. It points out that Ida Wells-Barnett was told to march in the back with other black women during the 1913 suffrage parade in Washington D.C. It also says that working class women in the suffrage movement often worked behind the scenes since they had to balance activism with their employment, whereas the women at the center of the movement often came from backgrounds of privilege and status.

[pullquote speaker="Carrie Chapman Catt" photo="" align="center" background="on" border="all" shadow="on"]The vote is a power, a weapon of offense and defense, a prayer. Use it intelligently, conscientiously, prayerfully. Progress is calling to you to make no pause. Act![/pullquote]

A panel dedicated to Vermont discusses the rather small suffrage movement in the state. It attributes the lack of a widespread movement to the rural nature of the state compared to neighboring New York, which had a very active suffrage movement. A separate timeline also features important milestones here at Middlebury. The college — founded as an all-male institution — became coeducational in 1883, and the Chellis House opened on campus in 1993 as a resource for female students.

As we celebrate the centenary of women’s suffrage in the U.S., the exhibit reminds us that further progress still needs to be made to secure voting rights for all Americans. According to the exhibit, the 15th and 19th Amendments were worded as vaguely as possible and, as a result, allowed for the possibility of poll taxes and other disenfranchisement techniques. For instance, black women could not vote until the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Even today, citizens in Puerto Rico and other U.S. territories cannot vote in federal elections even though they are just as American as those in the 50 states. Many states have attempted to enact strict identification laws that disproportionately affect certain marginalized groups.

Morsman concluded her opening remarks with an uplifting quote from Carrie Chapman Catt: “The vote is a power, a weapon of offense and defense, a prayer. Use it intelligently, conscientiously, prayerfully. Progress is calling to you to make no pause. Act!”

Catt said these words in celebration of the 19th Amendment being ratified in 1920, but they are just as applicable today.

The “Votes… for women?” exhibition will remain open through Dec. 8. Professor Morsman will also discuss key strategies of the suffrage movement this Thursday, Sept. 26 at 7 p.m. in the Museum.

Emmanuel Tamrat '22 is Digital Director.

He began working for The Campus as a photographer and online editor in the fall of 2018, and previously served as senior online editor.

An Environmental Policy major, Tamrat hails from London, GB but calls Alexandria, VA home. At Middlebury, he is involved in Rethinking Economics and works as a Democracy Intiatives Intern with the CCE.