After a decade-long crusade of student activism, Middlebury has begun its long march toward divestment. In a unanimous decision last January, the Board of Trustees approved Energy 2028—an ambitious and sweeping plan that promises certain reductions of the college’s environmental footprint in response to the mounting climate crisis. With the vote, the board set a timeline for meeting a series of environmentally-minded goals and initiatives.

In terms of divestment, the first of these dates was Aug. 1 of this year, when the college pledged to halt all new direct investments in the fossil fuel industry. The college currently has 5.1% of its endowment directly invested in fossil fuels — a dollar amount of $53.5 million. Looking ahead, the college plans on divesting that sum in stages — 25% reduction by 2022, 50% by 2027, and a total 100% by 2034.

According to 350.org, a Middlebury-founded national environmental organization, about 40 U.S. educational institutions have divested thus far. And Middlebury’s commitment is more extensive than many others (Columbia and Stanford have pledged only to divest from coal companies). The college will divest not only from companies whose core business is oil and gas production, but also those that are involved on the infrastructure end, whether through equipment, pipelines or services.

Divestment at American colleges

Full divestment refers to institutions that committed to divest from any fossil fuel companies.

Partial divestment refers to institutions that committed to divest from some fossil fuel companies, or to divest from all fossil fuel companies but only in specific asset classes.

Coal only divestment refers to institutions that committed to divest from any coal companies.

The Middlebury divestment campaign began in 2011, but gathered steam over the past few years. Waves of students have adopted the campaign as earlier activists have graduated. The final push was led by a group of sophomores in 2017 who devoted themselves to drafting presentations and organizing rallies under the umbrella of the Sunday Night Environmental Group (SNEG). The fact that these students weren’t graduating anytime soon certainly helped in abating the trouble of generational turnover, students and college officials say.

According to one of the leaders on the forefront of Divest Middlebury, Zoe Grodsky ’20.5, the intense time commitment the campaign required leading up to the board’s vote prompted students to dial back their activism or put their focus elsewhere after the fact.

“We’re all pretty burnt out after what happened in January,” she said. “We haven’t necessarily been working on accountability.”

Indeed, there does not appear to be any structure in place for the administration to communicate divestment milestones to the Middlebury community. And now that the confetti has settled on the board’s landmark vote, the college has done little to tout its progress. (The Aug. 1 benchmark came and went with little fanfare.) But in interviews, Middlebury’s financial officers and student leaders have painted a picture of a college working to make good on its promises, despite a lack of transparency at the outset.

Bottom: Bill McKibben, an environmental activist and scholar at the college, addresses the crowd during a rally outside Old Chapel in support of fossil fuel divestment on Thursday, Oct. 19, 2017. (Silvia Cantu Bautista / The Middlebury Campus)

Contributing to a lack of communication seems to be the campaign’s generous timeframe: the Energy 2028 goal posts — stretched across 15 years, despite its name — will mean that the college won’t regularly, or even annually, meet major milestones that warrant announcements.

Still, in President Laurie Patton’s original address to the college last January, she said that the college hoped to beat the 15-year mark. “We understand that time is of the essence and that this is a floor and not a ceiling,” she said. “We will make every effort to get there quicker.”

From divest darties to suits and PowerPoints

As the campaign headed to the board earlier this year, the college decided to bundle its divestment plan with three other environmental goals: energy conservation, renewable energy and environmental education. Folding those initiatives into the divestment pledge was largely strategic, as college officials sought to make the plan more palatable to the trustees.

“The way that Energy 2028 is packaged makes it really hard for board members to say no,” said Cora Kircher ’20, a leading member of Divest Middlebury. “If you say ‘no’ to this one pillar, then you’re saying ‘no’ to all these other dimensions.”

At the same time, students changed their own tactics. After years of futile protests (and even a divestment-themed day party — dubbed “darty” — in 2013), a new generation of students took a more business-like approach to their campaign. In addition to arming themselves with statistics, they donned suits and high heels for a formal presentation to the board. It worked.

Divestment activism over time

The timeline below highlights key events in the history of student divestment activism and the resulting administrative responses. See here for a timeline detailing other key events on the road to divestment.

Click on an event to learn more.

2012

Students send an email to hundreds of students, staff and faculty announcing that "Middlebury Divests from War in Honor of Dalai Lama Visit." After the event, students write a follow-up email urging the College to divest from arms manufacturers, military contractors and fossil fuel companies.

2013

Divest Middlebury hosts a family-friendly day party outside of the spring trustee meeting. A student band plays and community members, a Middlebury professor and student organizers speak to the crowd.

In a message to the community, then-President Ron Liebowitz announces that the College would not be divesting. Liebowitz points to the board's "fiduciary responsibilities" and the "lack of proven alternative investment models" as primary reasons the board voted against divestment.

2015

Student activists engage in metaphorical tug-of-war games outside Atwater, Ross and Mead Chapel to demonstrate the pulls on Middlebury from students and corporations.

Students hold another day party outside Old Chapel during Trustee meetings and talk to a couple trustees on their way in and out of the meeting.

Divest Middlebury hosts a weekend of awareness that includes film screenings, a panel on climate justice and family-friendly events in town.

Student organizers meet with high-level administrative personnel, including President Laurie Patton; Bill Burger, former vice president for communications and chief marketing officer; Caroline McBride, Middlebury trustee; and Patrick Norton, former vice president for finance and treasurer of the College.

2017

Members of Divest Middlebury stage a "low-key" sit-in in Old Chapel during Spring trustee meetings, handing out materials and speaking with trustees.

Students and community members join Bill McKibben outside Old Chapel during a board meeting to advocate for divestment.

2018

In February 2018, SGA Feb senator Alec Fleisher '20.5, a key organizer of Divest Middlebury, calls for a referendum among students on whether the College should divest from fossil fuels. 79% of the student body votes in support of fossil fuel divestment.

Divest Middlebury activists spend the summer on calls with David Provost, the new executive vice president for finance and administration, and Middlebury trustees. Given seven options for how the College could work towards divestment, organizers narrow down options and continue negotiations with Provost and board members.

Three Divest Middlebury organizers present to the full Board of Trustees on fossil fuel divestment. Simultaneously, two members from Divest Middlebury give the same presentation outside to students and community members and then lead a rally in support of divestment.

Faculty votes 86 to 7 in favor of the SGA fossil fuel divestment bill.

2019

Wearing the hallmark Divest Middlebury color, students gather in Mead Chapel to write thank-you letters to the Board of Trustees and tell stories about the movement.

Following a unanimous vote to divest from fossil fuels by the Board of Trustees, the College announces the Energy2028 plan, which names divestment as one of its four key pillars.

Instead of making an emotional appeal about climate change and the fate of the planet, student activists tailored their argument, embracing the broader environmental plan put forward by the college and identifying key allies within the administration.

“We tried to go with the moral argument for so long,” Grodsky said. “And it should work. As an institution that cares about the human population, Middlebury should divest from fossil fuels. But that’s not enough and it just won’t be for any school.”

David Provost, the college’s treasurer, also emerged as an invaluable resource. “I think without David this wouldn’t have happened,” Grodsky said. “Identifying him as an ally was a huge game-changer.”

Elisa Gan ’20, the student liaison to the SGA on endowment affairs and the only student member of the board’s Investment Committee, estimated that Provost devoted some 300 hours to the divestment issue since joining the college in 2017, via strategy sessions and negotiations. Provost coached students through divestment presentations and walked them through financial jargon, teaching them the language they needed to speak on the Investment Committee’s terms.

Despite the uphill battle waged by students (the trustees had voted against divestment in 2013), the college has a long history of environmental stewardship.

“In the seventies, this college made a point to be the first college in America to have an Environmental Studies program and the first to say we were going to achieve carbon neutrality,” Provost said. “We have been at the leading edge of addressing climate change. If it were anyone’s position to lead in this space, it is Middlebury College.”

Energy 2028 (or 2034?)

While some students were taken aback that divestment under “Energy 2028” would be implemented in 15 years, not 10, others praised aspects of Middlebury’s ultimate divestment plan. “What I was excited about was how they defined fossil fuels,” Kircher said. “They included pipelines and infrastructure. They have the largest definition of what fossil fuels are from any divestment movement.”

But with a longer roll-out? “The 15-year thing is not great,” she conceded.

College officials say, in their defense, that divestment is not a quick process, given the Wall Street mantra to buy low and sell high. “The board was most concerned that if we had done what the students had asked of ‘Sell all your fossil fuel assets today,’ and fossil fuel investments were depressed at that time, we would be walking away from money,” Provost said. “And that would fly in the face of the Board’s fiduciary responsibility.”

The 15-year plan was settled on during negotiations with the college’s investment manager, Investure. The Virginia-based equity firm oversees the majority of the college’s endowment through a “hands-off” structure in which managers have free reign over what they decide to invest. But in response to Middlebury’s demands, Investure agreed to facilitate complete fossil fuel divestment through the creation of “fossil-free portfolios.”

In order to transition the college’s current endowment portfolio from fossil fuels in compliance with Investure's model, the college needed time.

“Fifteen years is simply the amount of time that every transaction we’re currently invested in goes on its natural progression of maturing and then new money coming back in,” Provost said. “The last one of those, the furthest one out, was 15 years. The maturity is going to be done in the seven to eight-year time frame. We estimate that the 5.3% will be significantly below 1% by 2028. Fifteen years is just the tail.”

Where is the money?

Continued resistance to divestment came from Investure’s former CEO, Alice Handy. Her departure in 2018 led to new conversations on how the firm could accommodate Middlebury’s environmental stewardship.

But Middlebury is not alone among colleges in outsourcing its financial investment decisions. Although Middlebury is Investure’s largest client, Smith College works with the same firm and recently followed Middlebury’s lead in announcing its commitment to divest from fossil fuels Oct. 18.

But proprietary concerns make the endowment’s investment portfolio difficult to publicly disclose. As of Dec. 31, the college had a total of $1.04 billion invested through Investure. Of that total, $53.5 million was “exposed” to the fossil fuel industry (meaning, directly or indirectly in the fossil fuel industry) while only a fraction of that is directly invested in coal, with $950,000 or 0.1% of the entire endowment. Yet in the last three years, the college’s fossil fuel investments have grown by $10 million.

According to Provost, there is another $100 million of the endowment that is not accounted for in Investure’s holdings. These are privately invested through donations with specific stipulations.

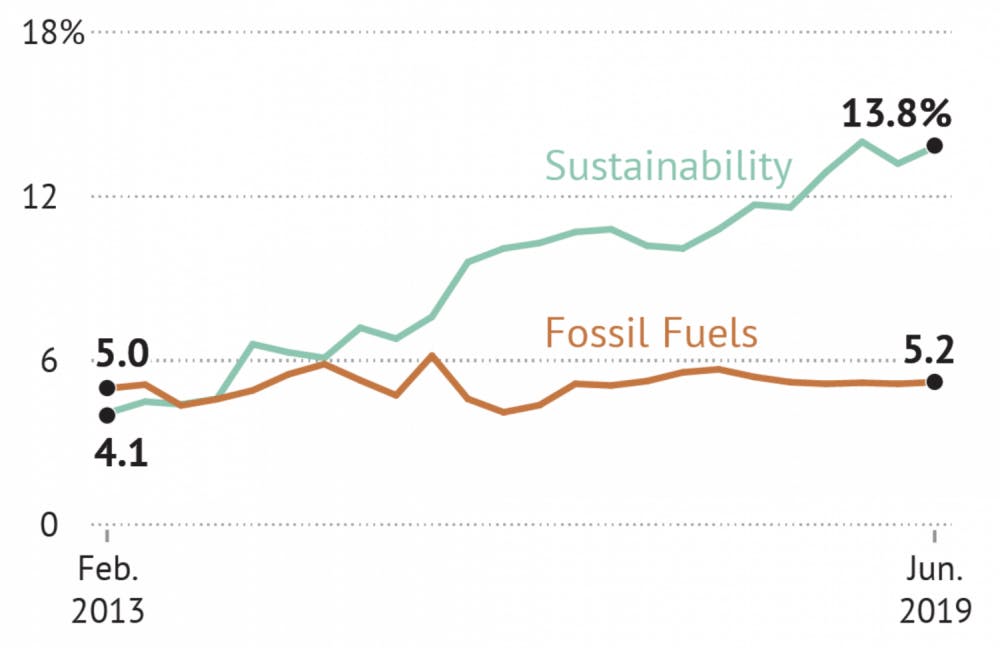

In contrast to its financial foothold in fossil fuels, the Board of Trustees has repeatedly voted to ramp up sustainable investments in the last decade. The most drastic change came in 2014 when the Investment Committee upped its commitment to sustainable investment to $50 million (from the mere $4 million endorsed four years prior). This move followed the time the board explicitly voted against divestment in 2013.

The $50 million commitment alone pushed the college’s investments in sustainable assets to eclipse those in fossil fuels. Since then, the board has voted to move an additional $19.3 million into sustainable assets. According to Patton, the endowment’s stake in sustainable investments will continue to grow in tandem with its decrease in fossil fuels.

“You will see a continued increase in ESGs and renewable assets as they come on the market,” Provost said. “We’re finding more now and I expect those will continue to grow.”

The slippery slope

One of the greatest concerns of divestment skeptics was the “slippery slope question” — that divesting from fossil fuels would inevitably lead to students returning to the Board year after year demanding additional divestments from other controversial sectors.

“The board wanted to make sure that they weren’t being asked by students every year to divest from another sector,” Provost said.

During the faculty referendum last year — when a notable 92% voted in favor of divestment — one professor expressed concern. “What’s next? Arms? Prisons? Pornography?” they allegedly said, according to faculty present at the meeting.

The board’s concerns may not have been simply conjectural either. Those involved in the Divest Middlebury movement, along with SGA members, are now raising concerns about privatized prison investment, amid the national campaign against mass incarceration. An SGA email sent out to some students last week solicited opinions on the college’s financial stake in such prisons.

Gan, the student liaison who is uniquely allowed to attend the trustees’ Investment Committee meetings, is responsible for serving as a bridge between students and board members. This year, newly-elected, Gan plans to spark conversations between the board and the student body on issues such as private prisons and weapon manufacturers.

Some students think the slippery slope shows students are moving in the right direction. According to them, as ethically dubious investments come to light, the college should be removing its financial links.

“In a dream world, I think that we should be divesting from prisons, from arms,” Kircher said. “Yeah, please — bring on the slippery slope.”