“Even though it’s idealized, it felt pretty real.”— Donovan Compton ’23

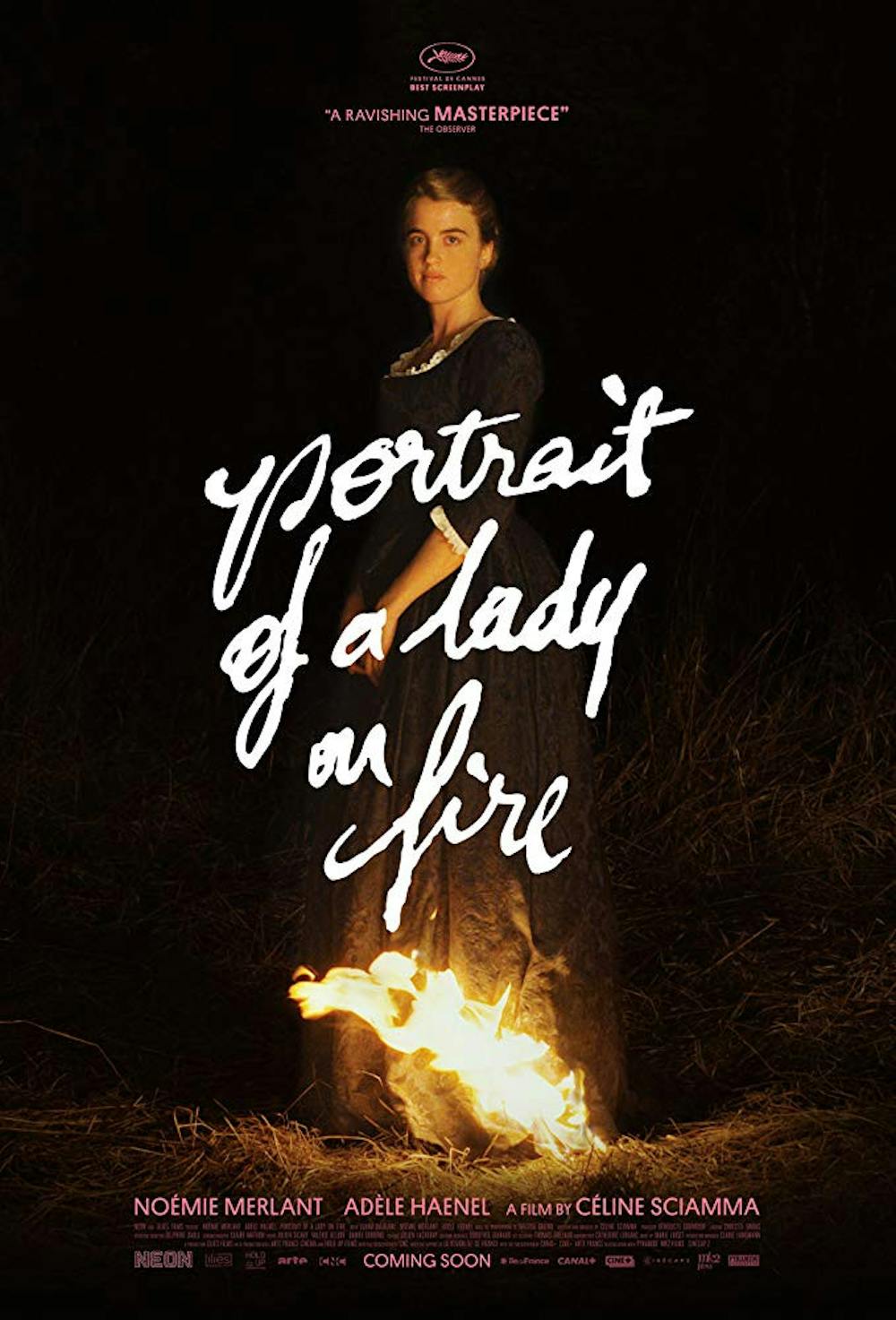

In the best of ways, this film brings us back into a simultaneously dreamy, yet dreary world of reimagining sexuality in our society. Director Céline Sciamma orchestrates a gorgeous French historical drama in “Portrait of a Lady on Fire.” Brought to the college by the Hirschfield Film Series on Nov. 2, “Portrait” reinterprets the Greek myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, tugging at your heartstrings in a mixture of wry humor, beautiful cinematography and tender shifts in understanding love. In the best of ways, leads Marianne (Noémie Merland) and Héloïse (Adèle Haenel) dance around each other in a passionate performance.

“Portrait” takes place within the 18th century through the memories of Marianne, an artist both teaching and posing for her class, advising students as they sketch her. Emotions begin to run high as a student brings out a portrait of a woman by the sea, garbed in a burning blue gown, painted by Marianne herself. The eponymous painting “Portrait of a Lady on Fire” transports Marianne back to years prior, starting with her journey to the memory.

Here, the story begins to unfold on a tumultuous boat trip to a remote island, where she is commissioned to paint a wedding portrait for a notoriously uncooperative subject, Héloïse. Vehemently opposed to being married off, Héloïse thus refuses to sit for a portrait and is introduced to us in sombre rigidity, eyes cloudy and cold. Thus, as Marianne masquerades as her companion on the island, hoping to familiarize herself with her features so as to paint in secret, viewers are guided through the fascinating push and pull of forces that join and sever the duo. Albeit a definite exaggeration of the autonomy of femininity, the stark contrast of this narrative from portrayals of women in other period films is refreshing.

Merland and Haenel encompass the subtle beauty of their relationship in the little details that shift with their bond. Growing past the stiffness, we are introduced to Héloïse the blues of her eyes grow warm with mirth, dark with passion and unreadably pensive as the film progresses. Likewise, Merland captures the role of the brooding, impassioned artist as she renders Marianne with a full honesty that engulfs her in the performance. As the memory unfolds, so does the depth of the story — beyond the leading women, “Portrait” examines forms of female empowerment.

Through tongue-in-cheek humor at the desperation to be unburdened with fulfilling traditional familial roles, independence is a driving force as the film chronicles the trials of Sophie, a maid, trying for an abortion with the aid of Marianne and Héloïse by her side. It’s almost wacky — between watching the trio try remedies such as pushing Sophie to sprint to watching a group of women chant as Marianne and Héloïse battle feelings across a hearth, the multidimensionality of empowerment is highlighted in their agency. You are greeted with a new sense of love; companionship, art and community are highlighted as Sciamma strays from the conventions of recapturing individuality.

Visually, the film stuns as characters traverse a background of blues evolving through coldness and warmth in conjunction to the shifts between Héloïse and her mother. Set on the cliffside, the manor adopts a pensive aura with walls of blue, slivers of mahogany sconces cleverly designed to hint at warmth. Candlelight flickers at every corner, adding to the ambiance and solitude that amplifies every emotion in their rawness. “Portrait” hits its stride with its aesthetics as viewers are easily immersed in a vignette of their universe. By displaying women of the time with a certain freedom that would never have been realized elsewhere, a new perspective is ultimately fostered in the audience as Sciamma revitalizes possibilities to define oneself within an era that leaves no room elsewhere to breathe.

Reel Critic: 'Portrait of a Lady on Fire'

Comments