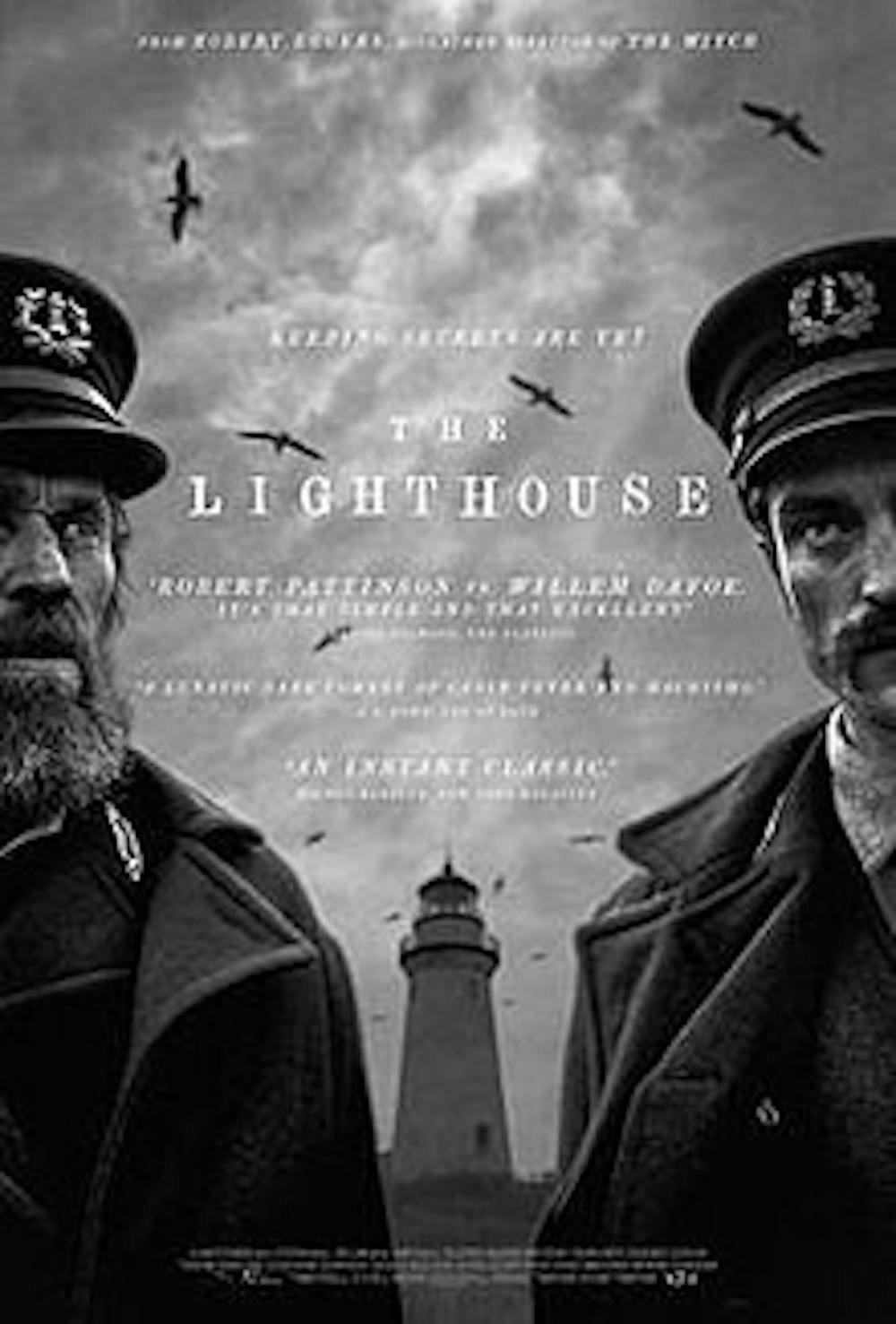

A brooding foghorn reverberates through the darkness, echoing in the vast blank expanse and chilling to the core. Before any visual is brought on screen, director Robert Eggers imbues “The Lighthouse” (2019) with a sense of resonant gloom that saturates the film an irrevocable dread.

Yet, as the film opens in its claustrophobic 1.19:1 aspect ratio, reminiscent of the works of early filmmaker Fritz Lang, its beauty is found in its grayscale. When making a film in black and white, most filmmakers would ensure separation from background by utilizing high-contrast lighting that places its composition in a combination of deep true-black and bright white, yet Eggers rejects this notion, instead often working within the middle-grounds. The composition is continually muddled, making it hard to discern a sense of place within the surrounding world. Every frame in this film is an oil painting; meticulously crafted in its apparent haphazardness and beautifully lit, swelling from the deepest, richest blacks through the shadowy grays, rarely reaching the unadorned, unadulterated whites. The foggy sea winds are ever-present, cutting through the rocky terrain and clamoring on the shabby wooden slats of the old lighthouse keeper’s cabin, encapsulating the island as a place all its own.

“The Lighthouse” finds wickie Thomas Wake (Willem Dafoe) and his assistant Ephraim Winslow (Robert Pattinson) at the opening of their four-week stay as keepers of a lighthouse off the coast of New England. At first, Ephraim is a man of regulation, refusing to partake in Wake’s alcoholic tendencies, yet as the dredge of manual labor wears on him, and hours turn into days turn into weeks, his threshold begins to near and his quenches his thirst. From his first arrival to the island, Ephraim discovers his limits; he is strictly forbidden from entering the light room of the lighthouse tower, Wake’s logbook is constantly locked in a chest of drawers and his daily actions are rigorously piled on. The island is shrouded in a thick layer of fog that heightens this sense of claustrophobia and mystery. Eggers’ decision to work within the 1.19:1 aspect ratio condenses the film, tightly engrossing the characters within it and his choice to highlight the middle gray tones works to make the troubled waters murky and unclear.

Wake and Winslow do not get along. Wake, is in command as the wickie, and his logbook, in which he records the daily ongoings, is held as gospel. Winslow is given a litany of orders that fills his day with exhausting, arduous tasks, leaving him completely abandoned of energy by the time dinner is set on the table. Wake constantly refers to Winslow as “Dog,” treats him like a mutt and forces him to sweat endlessly over wheelbarrows of coal and cistern cleaning. There is a clear power dynamic within the film: Wake is the overseer and Winslow’s sole job is to carry out the menial tasks required for the lighthouse to function. Yet the mental power dynamic is contested by the physical one: Winslow is much younger and fitter than his limping, feeble boss. As the film progresses, Winslow begins to question Wake’s authority and seeks to challenge it.

While the mystery of the film is tantalizing enough to satisfy viewers, “The Lighthouse” morphs into a psychosomatic, alcohol-fueled horror film that draws in the spirits of yore to haunt the newcomer. Wake warns Winslow of his previous assistant’s inability to cope with the imaginings of his mind, which allegedly caused his eventual death, but Winslow too soon falls prey to the trappings of lunacy. He sees mermaids lying amongst the rocky, seaweed-encrusted cliffs of the island, and is constantly tormented by a relentless sea bird, which Wake decries as possessing the souls of dead seamen. The film becomes unreliable in its information, causing the viewer to question the very basis of their understandings of time and place.

“The Lighthouse” brilliantly encapsulates the isolated hysteria of being entirely alone in the presence of a stranger, and how time and place can be lost when routine becomes ritual becomes mechanical. Walking out of the theater after this film is difficult. I found myself sitting in a daze as the theater employee walked by with his broom, trying to piece together the separation of reality from imaginings. It is, I will contend, nearly impossible to place just how long Wake and Winslow spent on the island. “How long have we been on this rock? Five weeks? Two Days? Where are we? Help me to recollect,” asks Wake of Winslow at the height of their collective derangement, both questioning his grasp on reality and the rapidity of his madness. “The Lighthouse” is a technically masterful work of art that uses the film medium to its utmost potential, warping the audio-visual experience into a crazed mania that deserves far more recognition than it has received. Go see “The Lighthouse,” but be sure to shed any expectations at the door and watch it with fresh eyes, for the joy of the film is in its unraveling.

Owen Mason-Hill ’22 is the Senior Arts & Culture Editor.

He previously served as a staff columnist, writing film reviews under the Reel Critic column. Mason-Hill is studying for a Film and Media Culture major, focusing his studies on film criticism and videographic essays.

His coverage at The Campus focuses primarily on film criticism, and has expanded to encompass criticism of other mediums including podcasts, television, and music under his column “Direct Your Attention.”