Most of the time, it is inadvisable to throw around adjectives of the “Kafkaesque-Orwellian” ilk; these words are overused. But hear me out on this one: “Atlantics” is the most Dickinsonian — as in Emily Dickinson — movie so far in the Hirschfield International Film Series. Consider the film’s opening scenes, which strongly echo the verse of that reclusive New England poet. A young woman spends a solitary night in her bedroom, staring at a flickering candle; the ocean wind brushes the curtains on a creaking windowsill; ghosts — yes, ghosts — haunt the neighborhood. This is, almost stanza-for-stanza, the stuff of “Because I Could Not Stop For Death.” Had Dickinson gone to the matinée screening I attended at Dana Auditorium, I’m reasonably certain she would have given “Atlantics” a glowing review. (“Wild film — wild film — nice cinematography — too many people in this movie theater — I have to run back to my house!”)

“Atlantics” takes place in a futuristic Dakar, Senegal, where economic disparities are ever-present. In the first scene, we learn that a skyscraper is being built by a team of construction workers who haven’t been paid their wages for the last four months, and that they can now barely support their families. One of these workers is Suleiman (Ibrahima Traoré), who has recently fallen for another man’s fiancée, Ada (Mame Bineta Sane). Ada, during her affair with Suleiman, starts questioning if she really wants to marry Omar (Babacar Sylla). Who can really blame her? Omar’s a materialistic bore who swims laps at his private pool all day. Suleiman, on the other hand, has sandy trysts with Ada on a beach that looks out on the Atlantic Ocean. We know which of these guys is the real deal.

At this point, “Atlantics” writer and director Mati Diop suddenly throws in two plot twists. Out of the blue, Suleiman and his coterie sail away from Senegal, looking for a better life in Spain. Shortly after the workers leave, though, their wives and girlfriends start to hear a sad rumor: that the boat to Spain might have sunk. Suddenly, the community’s women have lost their men, and the skyscraper’s construction tycoon, who apparently doesn’t feel the Bern, still won’t pay his workers’ families.

That’s the state of things when Plot Twist Number Two comes in: the body-snatching ghosts. The spirits of the dead sailors, we find out, have decided to mentally possess their lovers at night. Ada alone is the spectral exception — she’s much too busy adjusting to married life with Omar. But all the other women — seen mostly through the perspective of Ada’s friend Fanta — spend their wee hours with their eyes rolled back into pale visages, breaking into houses and committing arson. Both man and woman, visionless yet all-seeing, Fanta’s character seems to pay homage to Tiresias, the blind prophet of Greek myth who does not easily forget the sins of others.

Beyond the film’s most obvious lesson — “don’t hustle your employees or they will come back from the dead and destroy you” — there are subtler issues that “Atlantics” tackles. Ada, a religiously progressive Muslim, gets called “slut” several times in the film, and before Ada marries Omar, her in-laws require her to take a virginity test. It’s all the more ironic when the ladies of “Atlantics” become zombies: although the women act seemingly crazy, it’s only because they’re being possessed by the men. We never know if we should admire the drowned sailors’ empowering of Ada’s posse, or if they’re acting too clingy by transforming their wives into nocturnally indentured servants. Like the waves that crash onto the sand in the film’s beginning, the moral ambiguity of “Atlantics” both pummels and refreshens.

“Atlantics” rocks, and I want to see another Mati Diop film soon. Especially clever is how Diop organizes the story. We’re never confused in “Atlantics” because the film centers around a police investigation of an arson. As the cops learn the facts of the story, we learn with them.

Particularly notable is Amado Mbow’s performance as the bumbling lead investigator of the case. (The role is a cliché, but it’s a cliché that works.) His interrogation scenes with Ada crackle with chemistry, and one wishes that those two characters shared more screen time. Mbow’s best scene in “Atlantics” is towards the end. When the detective figures out that he himself might have been possessed by a spirit, he wears that look of sudden terror you get when, gazing out of the window at your lawn, you spot Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein rummaging through the contents of your garbage. It’s game over, man.

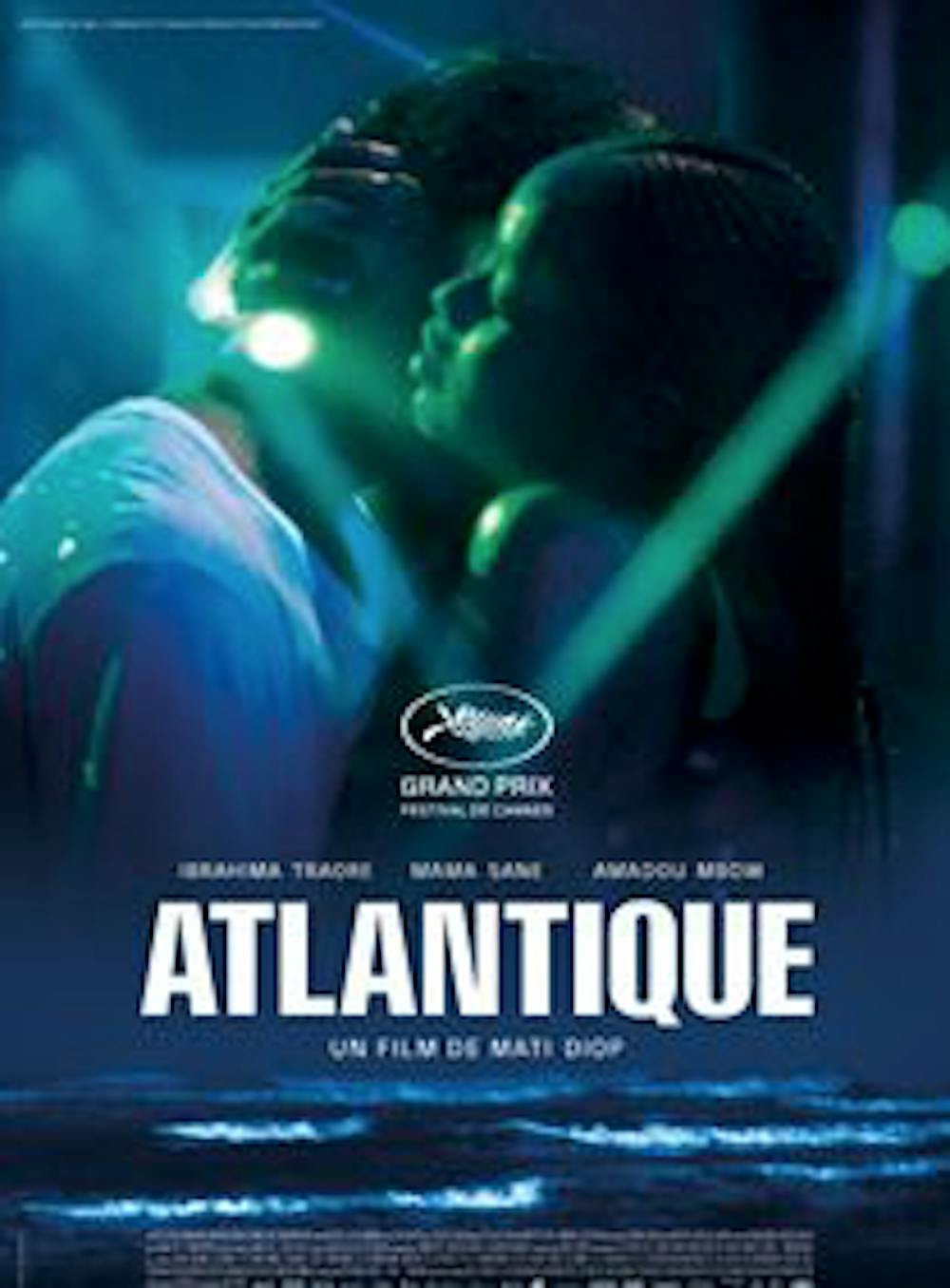

Reel critic: 'Atlantics'

Comments