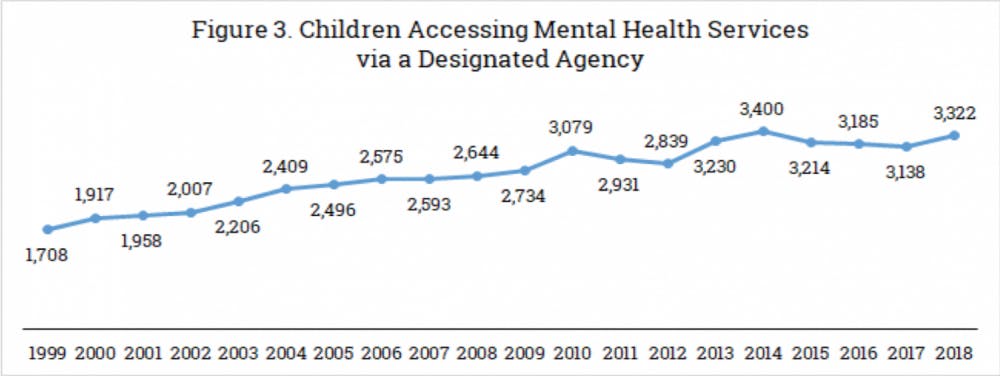

The number of children using mental health services in Vermont has doubled over the past two decades, according to a recent task force report from Building Bright Futures, a Williston-based non- profit. The report found that in 1999, roughly 1,700 children ages nine and under used mental health services in Vermont. Despite the state’s shrinking population, 3,322 children used the same services in 2018.

Building Bright Futures (BBF), a public-private partnership, monitors the state’s early care, health and education systems. Established in 2010 by law, it advises Vermont administration and legislation on early childhood policy.

Beth Truzansky, Deputy Director of BBF, sees the increase in mental health service use as a preventative measure rather than as a social response. The report results point to a cultural shift in mental health education and increased awareness of mental health services.

The BBF State Advisory Council formed an Early Childhood and Family Mental Health Task Force in 2019 to address the importance of mental wellbeing among Vermont children and families. In response to the notable increase in mental health service usage, both state and nationwide, the State Advisory Council started a conversation with Vermont families and spearheaded the report.

The 2020 report highlights the number of families with children under the age of nine who walk through the doors of Vermont mental health agencies. These families access crisis services and other forms of support, such as home-based therapy and case management. The study includes children in residential care, Vt. Dept. of Children and Family custody and specialized child care.

The increase in mental health service use does not reflect any particular cause. “It’s hard to point to one [factor],” said Cheryle Wilcox, Interagency Planning Director at Vermont Department of Mental Health and BBF State Advisory Council co-chair. She said, however, that familial trauma and substance abuse are major drivers.

Another definite contributor is the ongoing opioid epidemic and its impact on rural Vermont families. The number of babies born with opioid dependencies hit a peak about five or six years ago, according to the Department of Mental Health. Now entering elementary school, these children face greater mental health challenges than some of their peers.

“I would not call [the results] an epidemic,” Truzansky said. “We are trying to raise awareness that it’s good for people to find support when they need it and we want those supports to be available.”

“We don’t want a crisis,” she added. “We want to support kids and families so that when kids are adults, they can deal with whatever stressors that may come. We are investing in families so that kids are growing up in safe and supportive spaces in which they can build relationships.”

Although the report’s data does not indicate patients’ socioeconomic status, both Truzansky and Wilcox agree that lower income families are at a higher risk of mental illness.

The two said that, especially in rural Vermont, a lack of resources, transportation and employment add to mental stress.

“When parents are struggling through issues, their basic needs are also challenged,” Wilcox said.

COURTESY GRAPH

Page 7 of the BBF 2020 Report, which depicts the growing use of mental health services by children in Vermont over time.

Page 7 of the BBF 2020 Report, which depicts the growing use of mental health services by children in Vermont over time.

BBF has case managers that help connect families to resources to relieve food and housing insecurity, in an effort to ease the stress on parents. “With young children, their caregiver is the person that’s with them most of the time,” Wilcox said. “Therefore, it’s important for us and for everyone to support parents so that they have the capacity and support they need to be taking care of their children.”

Healthcare accessibility is also challenged by Vermont’s high cost of living and persisting decrease in population.

“There are a lot of vacancies in our community mental health agencies,” Wilcox said. “I think there’s this piece of young children who’ve experienced trauma, and then this issue of trying to recruit workforce and retain people.”

Wilcox added that working in childcare is often a labor of love.

“Early care and learning and mental health is not a high paying field,” she said. “That’s been tough — to have [enough] people in place to support children when they need help.”

Insurance is able to remove certain financial barriers to mental healthcare. Ninety-eight percent of children who access health service providers have their visits covered by insurance, the result of the federal mandate for child Medicaid.

Mental health agencies in Vermont accept Medicaid, as well as private insurance. “It’s something we do really well in Vermont — making sure patients are insured,” Wilcox said.

Currently, BBF works to elevate mental healthcare accessibility by coordinating with mental health agencies and early learning centers. In designated regions of Vermont, a BBF coordinator brings people together to address youth mental health on a local scale.

Within Addison County, BBF has worked with community mental health agencies, the Vermont Department of Health and other parent/child centers to launch an initiative called “Ok. You’ve Got This.” Its mission is to foster youth resilience through public awareness and educational campaigns. “It’s really about how we can make sure, with the challenges going on, that we instill hope and that people can bounce back from hard times,” Wilcox said. “‘Ok. You’ve Got This’ is a nice way to say that there are challenges, but there are things you can do.”

Efforts made by nonprofit organizations and public health agencies strengthen the availability of their resources. As young Vermont children and their families seek mental health services, they prevent depression, create stability and promote healthy development for generations to come. “We all go through hard times,” Wilcox said. “[But] there are specific things parents can do to help their children.”

Comments