In August, 1994 Emily Bernard was almost fatally stabbed in a coffee shop near her university. It was a few days before her birthday and she sat down at her college town’s coffee shop to write a paper for a class in the American Studies Program at Yale. It was a regular night until a balding man (who she describes as ‘Gallagher’-esque) took out a hunting knife and proceeded to stab her and six other people in what one news outlet described as a “blood bath.” Yet, Bernard can’t seem to find anger at the man. Despite the trauma it brought her and the medical issues she had to endure later on, she tells her therapist that it “wasn’t personal,” because she knew the man who stabbed her was not in his right mind.

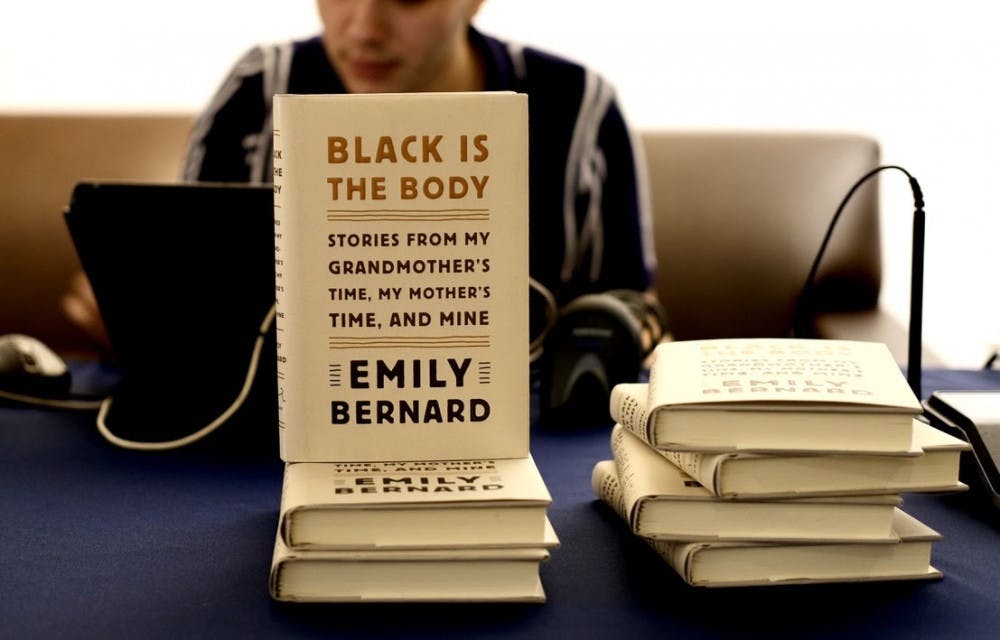

I’m saying all this to tell you that Bernard is a generous person, because I think understanding that is important to understanding her talk. If you’ve read the introduction to her book, “Black Is the Body: Stories from My Grandmother’s Time, My Mother’s Time, and Mine,” or even her author bio on the jacket, you know Bernard is most interested in “looking at ‘blackness at its border, where it meets whiteness, in fear and hope, in anguish and love.’” She’s dedicated much of her adult life to studying Carl Van Vechten, a white man who played a critical role in supporting the Harlem Renaissance. In her slideshow, she includes a picture he took of his dear friend Zora Neale Hurston, reciting a joke of hers about Van Vechten — “If Carl was a people instead of a person, I could then say, these are my people.”

Bernard is someone who believes in friendship, in its powers and in its ability to incur change.

Yet, as much as she believes in the power and ability of friendship, she also believes in its limitations. Bernard strongly believes that it is not the responsibility of people of color to educate white people.

Bernard, in response to a question posed by Lynn Travnikova ’20, pointed out the importance of self-care under our current regime. “We have to really take care of ourselves the best we can,” she said. “That’s the most important thing.”

It can feel confusing to reconcile her advice: too often in conversations around interracial friendships people of color are burdened with the feeling that they are responsible for their white friends’ re-education on race-related issues. Self-care and restoration tend to be painfully neglected. But Bernard is not arguing for one or the other. She’s doing something else, acknowledging this oft-forgotten grey area where friendships can simultaneously be helpful, but also not anyone’s job.

[pullquote speaker="Emily Bernard" photo="" align="center" background="on" border="all" shadow="on"]I believe in the power of intimacy and in the tender contract of conversation. I believe they have the potential to transform us. Racism is systemic and institutional, but people invent systems that create and inhabit institutions.[/pullquote]

Emily Bernard is a person who can forgive someone who stabbed her, who can laugh at her white friend’s ignorance (as she shared in her talk and her book), and is someone who really, really believes in the power of interacial friendships. While I think that’s beautiful for her, I don’t think that’s right or beautiful for everybody. As individual humans, we’re inherently going to have different responses to the confusing and heart wrenching drama we find ourselves and our country to be locked in. From workshopping with Bernard beforehand, seeing the thoughtful way she approached each of us, as individuals, I have a feeling she would feel the same way.

Bernard’s speech was not about declaring a ‘right way’ or invalidating the tactics of others. In the introduction to her book, she writes that she was looking to “contribute to the American racial drama” in a way that was true to life as she lived it. Her talk, like her book, is her truth. She was opening a door without closing any behind her.

Opening doors, starting conversations: 'Black is the Body'

SHIRLEY MAO/THE MIDDLEBURY CAMPUS

Comments