The longstanding success of Victor Hugo’s “Les Misérables” is, in part, its ability to transport us back in time. It is a triumphant work culminating in closure and French unity. But director Ladj Ly points to another gruesome reality.

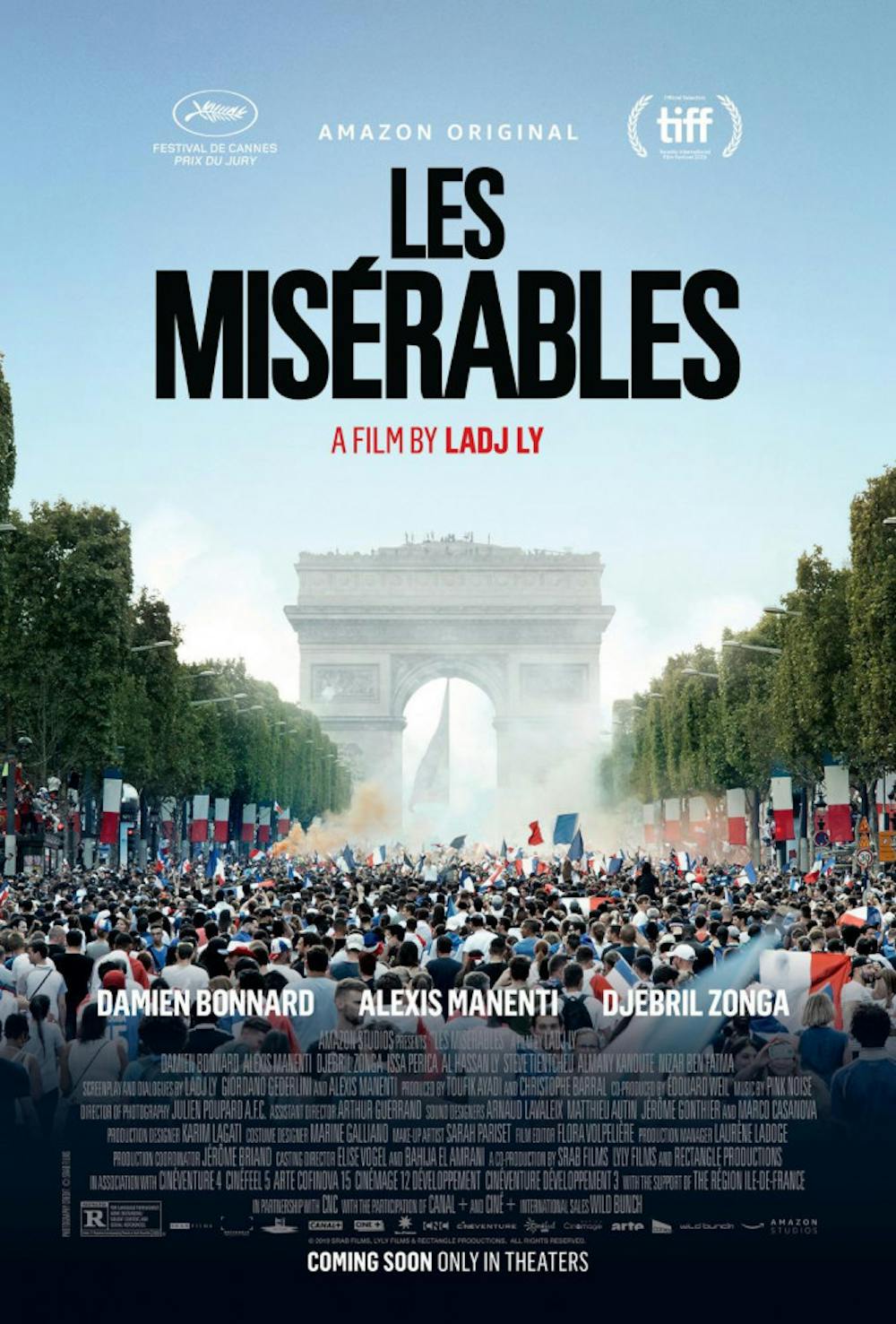

Presented to us by the Hirschfield Film Series, “Les Misérables” is a 2019 film that introduces viewers to the modern-day streets of Montfermeil, a scene shared by Hugo’s 1862 novel. Present Montfermeil replaces teetering brick shacks with cheap apartments crammed together in small spaces, surrounded by a landscape of litter. Most individuals are racial minorities, speaking a range of languages from French to Bambara. “Les Misérables” documents the violence, corruption and crime of today. Centered around Stéphane Ruiz (Damien Bonnard), a newcomer to the city and a new recruit of the Street Crimes Unit, or S.C.U., we follow his first patrols with two officers, Chris (Alexis Manenti) and Gwada (Djebril Zonga).

However, as Ruiz quickly discovers, the officers aren’t the dutiful individuals who we expect to defend and uphold the law, but instead its very abusers. Chris is the singular emblem of privilege, standing out like a sore thumb in the community he patrols. Gwada, hardened by growing up on the streets of Montfermeil, turns a blind eye as Chris, nicknamed “Pink Pig” by the mayor and children of the complexes, exploits his authority to frisk young girls. The horror comes to a head as the officers give chase to Issa (Issa Perica), a young boy who stole a lion cub. In a fit of rage, Gwada shoots him in the face with a flare gun. The confrontation is captured by a drone flying overhead, sending the officers into a state of panic. Through his portrayal of police brutality in impoverished areas of France, Ladj Ly points to the ongoing severity of social tension, and Victor Hugo’s century-old stories adopt new faces today.

Almost documentary-style, the film integrates several interesting scenes to tell a story of despair and disparity as Ly captures shaky shots of chases and the raw environment of Montfermeil. The beginning scene of a cheering crowd for the 2018 FIFA World Cup on the Avenue de Champs-Élysées is a portrait of unity — possibly the vision of hope Hugo paints in the final moments of his story. Almost instantly after, we’re brought back to run-down scenes of Montfermeil, where the buildings are cramped and the elevators out of service. Kids hang in abandoned lots, sliding down skate ramps on cardboard for fun. Meanwhile, Chris’ own children squabble not over whether they can afford food, but over turns on a Nintendo Switch, something likely unimaginable for the kids living in the derelict apartments. Capturing the ruptured, unjustly compromised childhood of the kids in Montfermeil, “Les Misérables” heavily juxtaposes our idyllic preconceptions of French life with clever expositions of inequity.

Ly’s decision to film pain and suffering in the city’s children is what hits heaviest. Little Issa, bloody and bruised from a run-in with the squadron, is left unattended. Buzz (Al-Hassan Ly), who filmed the confrontation, is also just a child. Yet, both were chased aggressively by the police. Watching grown men tackle children onto solid asphalt is a hard pill to swallow. As the mayor and even their parents throw them aside and neglect their own children due to the pressure of a dwindling economy, kids are largely left to fend for themselves. The hope in justice falters again and again when officers like Chris abuse their power, claiming, “I am the law!” Inevitably, when options are scant and authority is never on their side, the kids don black hoods and dark outfits and corner the squadron in a stairwell, pelting the officers with random objects and pushing shopping carts at them. The situation is grim and full of aggression. Bearing firecrackers as a nod to the flare gun previously used against Issa, the children improvise their attack to respond to the similar levels of pain and aggression they faced.

The movie ends on a dark note, with a bruised Issa holding up a lit Molotov cocktail in a dark stairwell at gunpoint. As he contemplates throwing the bottle, the screen fades to black. His performance fills us with the overwhelming sense of insecurity and mistrust Issa feels at the moment. The flames flicker, bringing the story to a bleak close.

Touchingly documenting the political discrepancies imbuing daily life in Montfermeil, “Les Misérables” rewrites the common misrepresentation of violence amongst minorities, who are often unfairly cast as scapegoats for the larger political structures that oppress them. It is difficult to confront the hypocrisy of institutions people come to trust, but Ly’s story narrates this inequity in an incredibly raw and touching way.

Reel Critic: 'Les Misérables'

Comments