Before I get into the usual business of my review, I’d first like to say that I hope you are all staying well in these chaotic times. I’m doing OK in frosty Minnesota, if not exactly thriving. Below is a summary of how I’ve spent my last fortnight:

George Orwell might have dubbed my routine “Down and Quarantined in Minneapolis and Saint Paul.” I begin each day at 11 a.m., breakfast at noon and try to walk around a lake near my house before dusk sets. At night I watch “Twin Peaks” while consuming buckets of Ben & Jerry’s Coffee Coffee BuzzBuzzBuzz ice cream. Sometimes I’m a renegade. On a whim, I might circle two lakes instead of one; “Mad Men” replaces “Twin Peaks;” I purchase a pint of Chocolate Fudge Brownie instead of my usual Coffee Coffee BuzzBuzzBuzz. Variety is the BuzzBuzzBuzz of life, I suppose.

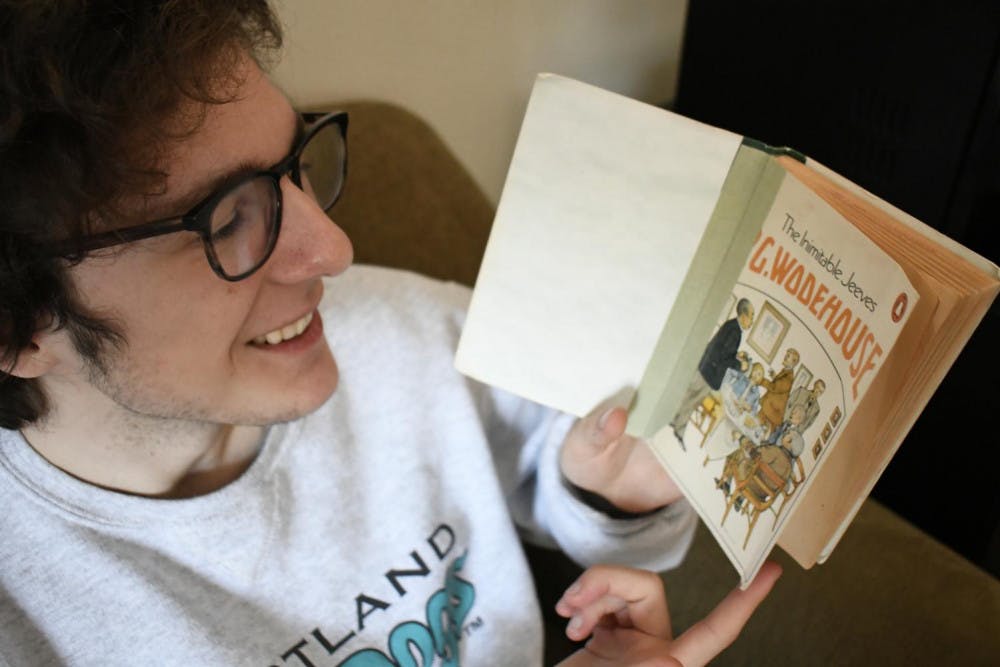

That’s what I’ve been up to. But enough about me; Let’s talk books.

I’ve recently finished “The Raj Quartet” (1965-1975) by Paul Scott, a novel sequence about the final days of British Crown rule in India during and directly after World War II. The series is about 2,000 pages, and it requires a fair amount of time to read. But Scott’s thoughtful prose and exciting narrative make the quartet an epic worthy of attention.

Another reason to try out “The Raj Quartet” is that it’s super hipster stuff: I only heard about the series a few months ago when I read that Stephen King recommended it. Kudos to Mr. King, because “The Raj Quartet” is usually absent from the “Giant-Books-To-Read-Before-You-Die” articles that one sometimes finds when surfing the web. (Those lists usually go: “Middlemarch” (1872), “Anna Karenina” (1878), “Moby Dick” (1851) and — additionally — “Middlemarch” (1872).)

The quartet’s first volume, “The Jewel In The Crown” (1966), focuses on the August 1942 riots following the arrest of Indian National Congress leaders. In a Southern province, the fictional Mayapore, India, Police Superintendent Ronald Merrrick takes advantage of the violence and chaos of the riots to arrest six innocent men in a sexual assault case that had occurred during the riots. The novel deals with the psychology behind Merrick’s blatantly racist arrests, and the consequences for one of the detainees — Hari Kumar, who’s been having a love affair with a “memsahib,” an Indian term for an upper-class, white Englishwoman.

“The Jewel In The Crown” is the series’ most morose installment, but the author injects more action as “The Raj Quartet” progresses to include scores of new characters in myriad, more varied situations. The proceeding books — “The Day of the Scorpion” (1968), “The Towers of Silence” (1971) and “A Division of the Spoils” (1975) — tell a hectic story of romance and warfare. One minute we’re at a tea party in Delhi, then suddenly we’re at a firefight in Burma. One character begins as a hard-drinking wastrel; at the quartet’s end, the same character commits a heroic sacrifice. Scott’s series has Iliadic ambitions, and one reads the last 500 pages as if they’re 50.

One is first struck with the beauty of Scott’ prose. “The Raj Quartet” tackles the same general themes of colonialism in India as E.M. Forster’s “A Passage to India” (1923) — particularly in the “Jewel In the Crown” — but where Forster’s writing emphasizes clarity and logic, Scott likes to hint at things, to suggest or even brood, and then to suddenly pull the rug from under our feet.

[pullquote speaker="" photo="" align="center" background="on" border="all" shadow="on"]Scott’s series has Iliadic ambitions, and one reads the last 500 pages as if they’re 50.[/pullquote]

“They found her thus, eternally alert, in sudden sunshine, her shadow burnt into the wall behind her as if by some distant but terrible fire,” goes the penultimate line in “The Towers of Silence.” A character has died, that’s fairly obvious. But what does “shadow burnt into a wall” actually mean? Why “sudden sunshine?” The next thing we learn is that this character died on the same day as the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima. The Hiroshima explosion was so bright that it left inverted shadows across the city, some by window frames and bridge railings, and some outlining the bodies of people caught in the blast. Through this historical allusion, an individual death becomes a deeply unsettling metaphor.

These books are jam-packed with history, too. In the quartet’s 2,000 pages, Scott gives the reader a fascinating account of mid-twentieth century India: the quartet discuss topics including the Muslim League/Congress rivalry that ramped up during WWII, Subhas Chandra Bose’s Japanese-backed Indian National Army, the creation of Pakistan, the sectarian massacres following the subcontinent’s partition and, most interestingly, the final days of India’s princely states. One learns so much reading these novels, and “The Raj Quartet” — unlike some Midd classes this semester — doesn’t even require Zoom.

But the most admirable aspect of Scott’s series is its lack of illusions about what the Raj represented (Kipling et al.). There’s certainly no love lost for imperialism in the quartet’s finale, “A Division of the Spoils.” “You honestly wonder where [imperial India’s administrators] come from,” says the character Captain Purvis. “Not England, surely?... The fact is places like [India] have always been a magnet for our throwbacks. Reactionary, unco-operative bloody well expendable buggers from the upper and middle classes who can’t and won’t pull their weight at home but prefer to throw it about in countries this….”

This sort of dark humor surfaces again and again in the “Raj Quartet.” Scott’s saying here that India was indeed ruled by some of England’s cruelest people. But, more importantly, he also suggests that the overseers of the Raj’s final days were of a largely pedestrian ilk: second-rate dullards of a crumbling empire.

Book Review: 'The Raj Quartet'

Comments