During a commercial break for a 1982 interview with Pat Buchanan, Richard Nixon once gave a succinct review of “The Path to Power,” the first installment in Robert Caro’s “The Years of Lyndon Johnson” series. “You know, there’s this terrible book out on [Lyndon Johnson], the Caro book.... Sh*t, it makes him appear like a goddamn animal,” Nixon said.

The ex-president — no stranger to the fouler side of human nature himself — pauses. “’Cause he was,” Nixon softly adds, grinning. “Means of Ascent” (1990) — the second volume in Robert Caro’s masterfully researched, still unfinished “Years of Lyndon Johnson” — is not only one of the most stylishly written accounts of a modern U.S. election but is also an electrifying thriller.

The book, which takes place from 1941 to 1948, first tells the story of how future president of the United States Lyndon Baines Johnson spent his “wilderness years” after losing the Democratic primary for one of Texas’ U.S. Senate seats in 1941. (In the 1940s, Texas was a Southern Democratic state — whoever won the Democratic primary was almost assured a win in the general election). The book’s last half recounts Johnson’s inglorious — and likely fraudulent — 87-vote victory in the 1948 primary against the state’s popular former governor, Coke Stevenson. “Means of Ascent” is also an unexpectedly hilarious biography because Caro — who has, somehow, spent half of his life writing about Lyndon Johnson — loathes Johnson.

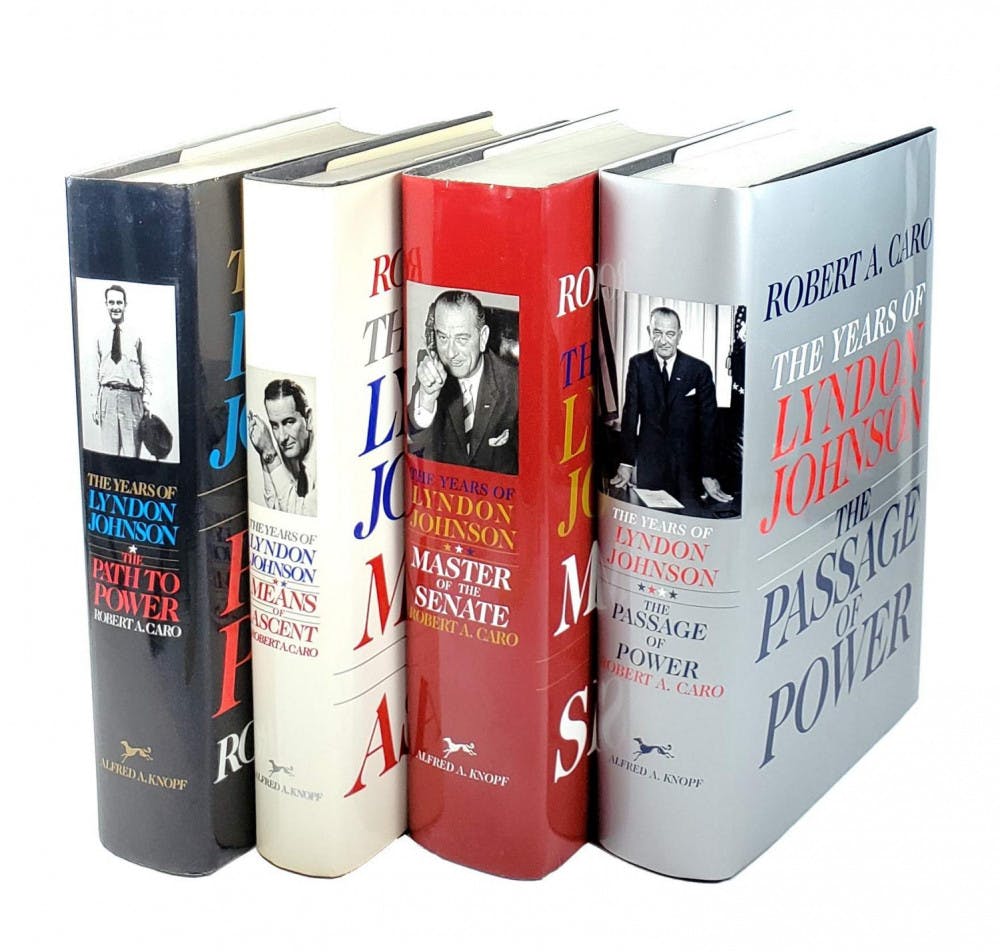

The series’ two later volumes, “Master of the Senate” (2002) and “The Passage of Power” (2012), show us Johnson’s slow shift to becoming a champion of the civil rights movement. However, the earlier “Path to Power” (1984) and “Means of Ascent” paint a bleaker picture of the politician, a side of Johnson’s personality that Caro suggests resurfaced in the 1960s when Johnson escalated U.S. military involvement in the Vietnam War. As we watch Johnson lie copiously, abuse his staff and bribe South Texas political machine employees (“pistoleros”) to stuff ballots for him, it becomes almost impossible to believe that the protagonist of “Means of Ascent” is the same man whose 1965 “We Shall Overcome” speech on the Voting Rights Act marked the sole occasion when Martin Luther King, Jr. wept in front of his friends, visibly moved by Johnson’s compassion.

Caro constructs the 1948 Senate race as a contest between two larger-than-life characters: Stevenson, 60, a libertarian cowboy, and Johnson, 40, a strikingly tall, crude political genius with a flair for showmanship. It's a great dramatic device because Johnson and Stevenson had few substantive issues when it came to actual policy. Stevenson was an avowed segregationist and bigot, for instance, while Johnson openly condemned Harry Truman's 1948 civil rights plan, dismissing it as a “a farce and a sham — an effort to set up a police state.”

But whereas the candidates’ politics converged, their campaigns strongly differed. Caro suggests that Stevenson’s campaign was the last of its kind: the former governor and a limited staff drove to an assortment of towns each day and delivered stump speeches at local courthouses. Stevenson never offered his stance on any major issues, instead relying on his stellar reputation as a laissez-faire governor. One campaign issue was Stevenson’s silence on the new anti-labor Taft-Hartley Act — which the uber-conservative Stevenson supported, of course, although Johnson tried to suggest that his self-proclaimed “Jeffersonian Democrat” opponent was in fact a pro-union socialist.

In contrast, Lyndon Johnson’s campaign was a wild grab for power that embodied the hectic style of political campaigning that became the norm in post-war America. Falling behind Stevenson, Johnson decided to invest in (then) modern campaign tools: his use of scientific polling, radio advertisements and millions of dollars in Big Oil fundraising were all unprecedented in statewide American politics.

The book’s most incredible passages recount how Lyndon Johnson’s campaign introduced another innovation to modern campaigning: helicopters. If Caro portrays Johnson as a villain in “Means of Ascent,” the book’s helicopter scenes turn Johnson into a full-on supervillain. “And then people would hear the hum in the sky,” writes Caro. “They would generally hear it some minutes before they could actually see the helicopter, but finally someone would shout, ‘There it is! Over yonder!’ and someone else would say ‘Look, it’s coming!’ — and people would begin pointing to the dot in the sky that was growing rapidly larger. As it drew closer, the hum became the distinctive, rhythmic, beating, chopping sounds…The helicopter would settle the ground with a last roar…a swirl of dust and pebbles swept into the air by its blades…And out into the silence stepped Lyndon Johnson.”

Johnson beat Stevenson in the Texas Senate Democratic primary by 87 votes, but in a merciless coda to “Means of Ascent,” Caro proves that Johnson probably lost the popular vote to Stevenson by thousands of uncounted votes. In what reads like an “Onion” article, Caro recounts the most egregious case of the many instances of voter fraud that the Johnson campaign likely committed. He writes, “The figure for Johnson which had been reported [in the ballot box for Texas’s 13th precinct] as 765 on Election Night, was now 965 — because, according to testimony that would later be given, someone had, since Election Night, added a loop to the ‘7’ to change it into a ‘9.’ Johnson had 200 more votes". To add insult to injury, we later learn that the 200 extra voters apparently “cast” their ballots in alphabetical order, because that is what was recorded on the 13th precinct’s registration sheet.

Later in his career, Johnson would brag with colleagues about how he stole the election, wanting his peers to not only know that he cheated, but that he cheated well. After his induction into the Senate thanks to an “87-vote” victory, the politician would even introduce himself to other Senators as “Landslide Lyndon.”

Unlike our 45th president, Johnson certainly had a sense of irony.