Non-traditional grading methods are rare in Middlebury classrooms, but some professors are “ungrading” and experimenting with “labor-based” and self-evaluative assessments as alternatives to letter grades.

“It just happens to work well because it’s a natural way to learn,” Biology professor Greg Pask said in reference to his “labor-based” grading system. “Regardless of what happens, this is what I was going to be doing anyway.”

Under Pask’s “labor-based” grading system, assignments are assigned different amounts of points; students may choose to forgo some assignments and still receive an A.

“Every single grade in my class aligns with how much work you put in,” Pask said.

Pask finds that students who have been historically disadvantaged under the traditional letter grade system perform much better under the labor-based approach. “I think the biggest benefit is that students are learning for themselves, they’re exploring this topic of our class for their own interests,” Pask said. “I think it really aligns with being a life-long learner, getting rid of extrinsic motivations and focusing on intrinsic [motivations] — things they really want to learn. Everything extrinsic just devalues the learning aspect of it.”

Professor of Computer Science Shelby Kimmel will employ two slightly different styles of grading this semester. In her Quantum Computing class, students will receive constructive feedback instead of letter grades for assignments and will have the opportunity to revise and resubmit work.

Kimmel plans to center the course around self-evaluation through student-created learning plans. Progress toward learning goals is tracked through meetings at the beginning, middle and end of the course.

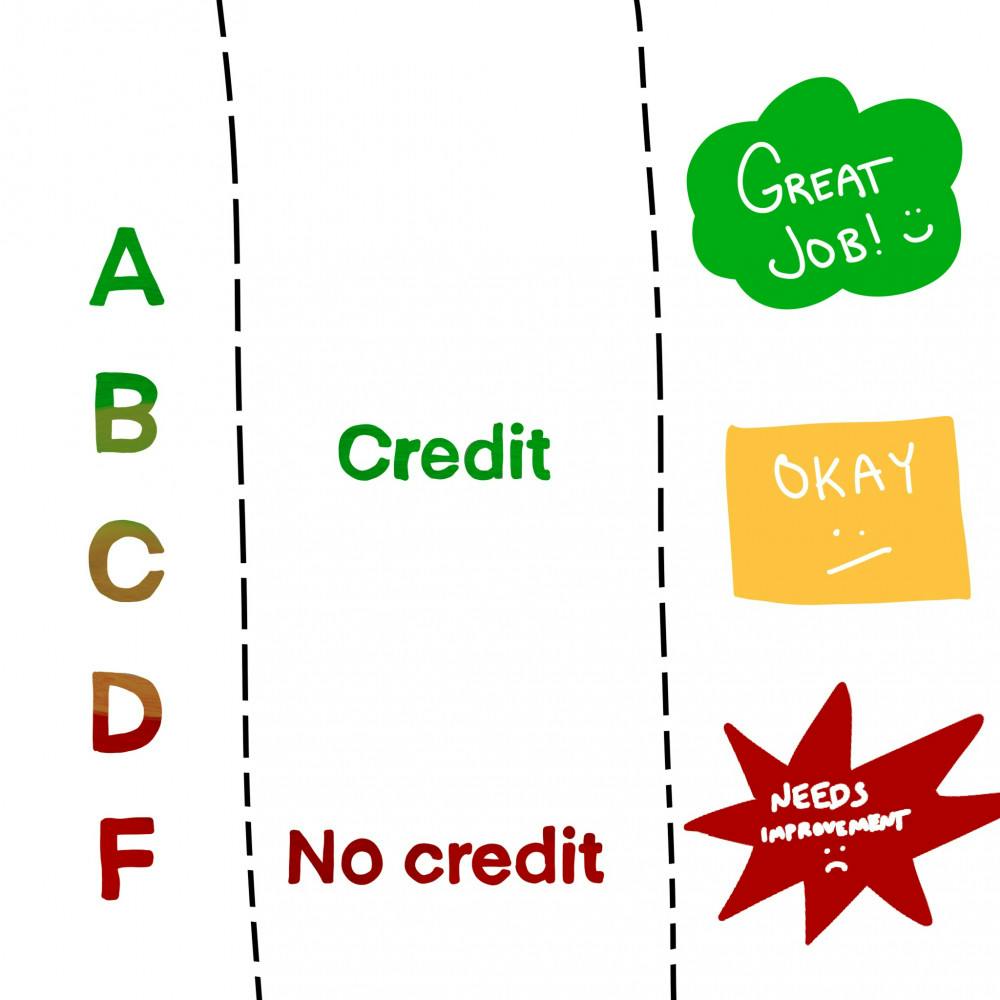

In her other course, Algorithms and Complexity, assignments are given “credit” or “no credit” evaluations and can be revised for credit based on feedback.

“While this credit/no credit system is more like grading, my goal is to give the students a bit more structure to help guide their learning, while also encouraging students to view learning as a process that requires time and effort and where mistakes are part of that process,” Kimmel said.

Like Pask, Kimmel cited the pursuit of equity in higher education as a motivation for her new approach to grading.

“I was personally influenced to make more significant changes this year by the Black Lives Matter movement and by becoming more aware of systemic inequities in our society and in higher ed, and how grades can play into issues of social justice,” Kimmel said.

Similar to Kimmel’s grading format, Political Science professor Kemi Fuentes-George has experimented with self-evaluative grading, including this past J-Term in his Protest Music in a Comparative Context course. Students evaluated themselves on assignments using a set of metrics, followed by a holistic final self-assessment.

“It’s important for people to understand that just because you get points that are fixed and numerically established, that there’s this perception that those points are objectively determined, and it's not necessarily the case,” Fuentes-George said.

While there is always the possibility of inaccurate self-perception, Fuentes-George still holds the authority to correct final grades if they don’t reflect the student’s actual effort — an aspect borrowed from Kimmel’s grading structure. However, this is often only necessary when students are too hard on themselves and assign a grade too low.

Grace Kellogg ’22, who took both Fuentes-George’s J-Term class and Pask’s Invertebrate Biology course, found increased motivation as well as disillusionment with letter-based grades. She said the biggest downside of non-traditional grading is that it still exists as the exception, overshadowed by an overall culture dominated by the letter grade system.

“For educators who truly care about the mental health of their students, now is the time to look into alternate learning models,” Kellogg said.

Mia Pangasnan ’23, a student who took Fuentes-Georges' J-Term course, instead believes that ungrading did not necessarily improve her own performance.

“If it is a course that has a plethora of participation opportunities, I feel like the students would feel comfortable with the ungraded method,” Pangasnan said. “If it is a class where the majority of the students' grades are determined by a limited number of assignments to be turned in, then I think that the ungraded method could potentially cause undue stress.”

Lily Jones ’23, a student of Fuentes-George's J-Term course, expressed that her initial skepticism toward “ungrading” was quickly turned around.

“What ended up happening though was that I was even more motivated than in other classes because I have the clearest understanding of what A-quality work is for myself,” Jones said. “Whereas in past classes I've taken, I've felt like the grading was out of my control, in this case, I knew exactly what I had to do to feel that I deserved a high grade.”

Editor’s Note: Lily Jones ’23 is a senior writer for The Campus.

Maya Heikkinen '24 (she/her) is a Copy Editor.

She has previously served as an Editor at Large, News editor, copy editor and staff writer. Maya is majoring in Conservation Biology with a minor in Spanish, but is also passionate about writing. She is from Orcas Island, WA, and loves being immersed in forests, running/hiking, gardening, and hanging with plants and cats. In addition to The Campus, she has been involved in SNEG and the currently extinct WildMidd.